The Undying One by Lafcadio Hearn

“The Undying One” was first published, 18 September 1880, in The New Orleans Item. In 1914, the story was reprinted in the anthology Fantastics and Other Stories.

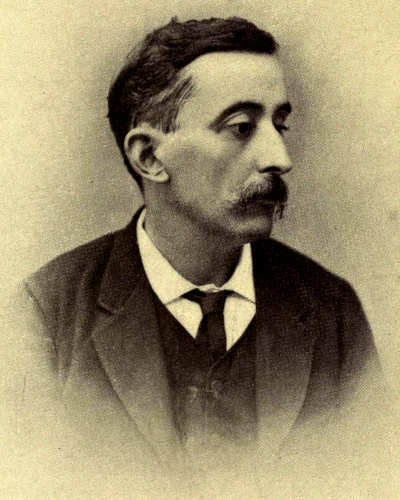

About Lafcadio Hearn

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was a writer, teacher, and translator, who had a very productive life and was a prolific author of speculative fiction. He was Born 27 June 1850, on the Ionian Island of Lefkada, but spent most of his early life in Dublin, Ireland.

When he was 19 years old, Hearn emigrated to the USA and began working as a newspaper reporter. Following a stint working for a newspaper in New Orleans, he became a correspondent to the French West Indies, remaining on the island of Martinique for two years, before relocating to Japan, where he spent the rest of his life. In 1891, he married Setsuko Koizumi, a lady from a high-ranking Samurai family. The couple had four children.

Hearn’s writings about Japan were fundamental in providing the Western world with an insight into what was then an unfamiliar culture. In 1894, many of his articles and essays were collected and published as the two-volume book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

Hearn was at his most prolific between 1896 and 1903, while working as professor of English literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo. He wrote four books during this time, including a collection of supernatural stories called Ghostly Japan (1899).

In addition to producing his own work, Hearn also a translated many of Guy de Maupassant’s stories from French to English.

Lafcadio Hearn died in Tokyo, on 26 September 1904.

The Undying One

by Lafcadio Hearn

(Online Text)

I have lived for three thousand years; I am weary of men and of the world: this earth has become too small for such as I; this sky seems a gray vault of lead about to sink down and crush me.

There is not a silver hair in my head; the dust of thirty centuries has not dimmed my eyes. Yet I am weary of the earth.

I speak a thousand tongues; and the faces of the continents are familiar to me as the characters of a book; the heavens have unrolled themselves before mine eyes as a scroll; and the entrails of the earth have no secrets for me.

I have sought knowledge in the deepest deeps of ocean gulfs;—in the waste places where sands shift their yellow waves, with a dry and bony sound;—in the corruption of charnel houses and the hidden horrors of the catacombs;—amid the virgin snows of Dwalagiri;—in the awful labyrinths of forests untrodden by man;—in the wombs of dead volcanoes;—in lands where the surface of lake or stream is studded with the backs of hippopotami or enameled with the mail of crocodiles;—at the extremities of the world where spectral glaciers float over inky seas;—in those strange parts where no life is, where the mountains are rent asunder by throes of primeval earthquake, and where the eyes behold only a world of parched and jagged ruin, like the Moon—of dried-up seas and river channels worn out by torrents that ceased to roll long ere the birth of man.

All the knowledge of all the centuries, all the craft and skill and cunning of man in all things —are mine, and yet more!

For Life and Death have whispered me their most ancient secrets; and all that men have vainly sought to learn has for me no mystery. Have I not tasted all the pleasures of this petty world,—pleasures that would have consumed to ashes a frame less mighty than my own?

I have built temples with the Egyptians, the princes of India, and the Caesars;—I have aided conquerors to vanquish a world;—I have reveled through nights of orgiastic fury with rulers of Thebes and Babylon;—I have been drunk with wine and blood!

The kingdoms of the earth and all their riches and glory have been mine.

With that lever which Archimedes desired I have uplifted empires and overthrown dynasties. Nay! like a god, I have held the world in the hollow of my hand.

All that the beauty of youth and the love of woman can give to make joyful the hearts of men, have I possessed;—no Assyrian king, no Solomon, no ruler of Samarcand, no Caliph of Bagdad, no Rajah of the most eastern East, has ever loved as I; and in my myriad loves I have beheld the realization of all that human thought had conceived or human heart desired or human hand crystallized into that marble of Pentelicus called imperishable,—yet less enduring than these iron limbs of mine.

And ruddy I remain like that rosy granite of Egypt on which kings carved their dreams of eternity.

But I am weary of this world!

I have attained all that I sought; I have desired nothing that I have not obtained—save that I now vainly desire and yet shall never obtain.

There is no comrade for me in all this earth; no mind that can comprehend me; no heart that can love me for what I am.

Should I utter what I know, no living creature could understand; should I write my knowledge no human brain could grasp my thought. Wearing the shape of a man, capable of doing all that man can do,—yet more perfectly than man can ever do,—I must live as these my frail companions, and descend to the level of their feeble minds, and imitate their puny works, though owning the wisdom of a god! How mad were those Greek dreamers who sang of gods descending to the level of humanity that they might love a woman!

In other centuries I feared to beget a son,—a son to whom I might have bequeathed my own immortal youth;—jealous that I was of sharing my secret with any terrestrial creature! Now the time has past. No son of mine born in this age, of this degenerate race, could ever become a worthy companion for me. Oceans would change their beds, and new continents arise from the emerald gulfs, and new races appear upon the earth ere he could comprehend the least of my thoughts!

The future holds no pleasure in reserve for me:—I have foreseen the phases of a myriad million years. All that has been will be again:—all that will be has been before. I am solitary as one in a desert; for men have become as puppets in my eyes, and the voice of living woman hath no sweetness for my ears.

Only to the voices of the winds and of the sea do I hearken;—yet do even these weary me, for they murmured me the same music and chanted me the same hymns, among aged woods or ancient rocks, three thousand years ago!

To-night I shall have seen the moon wax and wane thirty-six thousand nine hundred times! And my eyes are weary of gazing upon its white face.

Ah ! I might be willing to live on through endless years, could I but transport myself to other glittering worlds, illuminated by double suns and encircled by galaxies of huge moons!—other worlds in which I might find knowledge equal to my own, and minds worthy of my companionship,—and—perhaps—women that I might love,—not hollow Emptinesses, not El-women[1] like the spectres of Scandinavian fable, and like the frail mothers of this puny terrestrial race, but creatures of immortal beauty worthy to create immortal children!

Alas!—there is a power mightier than my will, deeper than my knowledge,—a Force “deaf as fire, blind as the night,” which binds me forever to this world of men.

Must I remain like Prometheus chained to his rock in never-ceasing pain, with vitals eternally gnawed by the sharp beak of the vulture of Despair, or dissolve this glorious body of mine forever?

I might live till the sun grows dim and cold; yet am I too weary to live longer.

I shall die utterly,—even as the beast dieth, even as the poorest being dieth that bears the shape of man; and leave no written thought behind that human thought can ever grasp. I shall pass away as a flying smoke, as a shadow, as a bubble in the crest of a wave in mid-ocean, as the flame of a taper blown out; and none shall ever know that which I was. This heart that has beaten unceasingly for three thousand years; these feet that have trod the soil of all parts of the earth; these hands that have moulded the destinies of nations; this brain that contains a thousandfold more wisdom than all the children of the earth ever knew, shall soon cease to be. And yet to shatter and destroy the wondrous mechanism of this brain—a brain worthy of the gods men dream of—a temple in which all the archives of terrestrial knowledge are stored!

* * *

The moon is up! death-white dead world! —couldst thou too feel, how gladly wouldst thou cease thy corpselike circlings in the Night of Immensity and follow me to that darker immensity where even dreams are dead!

Lafcadio Hearn (1850 — 1904)

______________________________

1. “El-women” appears to be a misspelling, or alternate spelling of “Ellewomen“, a form of Scandinavian fairy folk or elf-woman.

______________________________