The Curious Vehicle by Alexander W. Drake

“The Curious Vehicle” was first published in the December 1893 issue of The Century Magazine. In 1916, the story was reprinted in Three Midnight Stories. Nearly a century later, in 2008, “The Curious Vehicle was included in the mixed-author anthology Christmas Stories Rediscovered: Short Stories from The Century Magazine, 1891-1905.

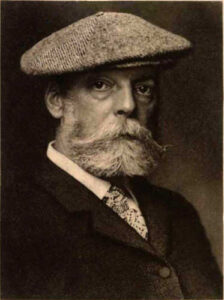

About Alexander W. Drake

Alexander Wilson Drake was an American artist, collector and critic. He also wrote fiction and poetry, but primarily worked as a wood engraver and was a driving force behind the new school of wood engraving in America.

Drake was also an art collector. His collection included a diverse range of items including antique samplers, wallpaper, antique silver cups, fragments of printed chintz cloth, paintings, and finger rings. The Drake Collection was auctioned 1913, after his death. Three years later, in 1916, The Century Company published several of Drake’s short stories and poems in Three Midnight Stories. The anthology also contained some of his engravings and photographic prints. Largely a homage to Drake, the print run consited of 500 hand-numbered copies. These were distributed to his family and friends.

The Curious Vehicle

by Alexander W. Drake

(Online Text)

It was midnight in early December. A dense silver mist hid the sleeping city, the street-lamps gave a faint yellow glimmer through the almost impenetrable gloom, the air was like the cold breath from the dying, the fog hanging in great drops from my clothing. Stray policemen had taken refuge in sheltering doorways, and my own footsteps echoed with unfamiliar and uncanny sound down the long street—the only sound that broke the midnight stillness, save the hoarse whistles of wandering and belated ferry-boats on the distant river.

As I emerged from a narrow street into the main thoroughfare, my shivering attention was attracted to a curious covered vehicle standing in the bright glare of an electric light. It was neither carriage nor wagon, but an odd, strongly made affair,” painted olive green, with square windows in the sides, reaching from just above the middle to the roof, and a smaller window in the back near the top. On each side of the middle window were two panels of glass. From the middle window only a dim light shone, like a subdued light from a nurse’s lamp. On the seat in front, underneath a projecting hood, sat a little old black man wrapped in a buffalo-robe[1] and a great fur coat partly covered with a rubber cape or mackintosh, with a fur cap pulled down over his ears. The horse was heavily blanketed, and also well protected with rubber covers. Both man and beast waited with unquestioning patience. Both seemed lost in reverie or sleep.

With chattering teeth I stood, wondering what could be going on in that queer box-like wagon at that time of night. The silence was oppressive. There stood the dimly lighted wagon; there stood the horse; there sat the negro—and I, the only observer of this queer vehicle.

I stepped cautiously to the side of the wagon, and listened. Not a sound from within. Shivering and benumbed, I, too, like the policemen, took refuge in a doorway, and waited and watched for some sound or sign from that mysterious interior. I was too fond of adventure to give it up. It seemed to me that hours passed and I stood unrewarded. Just as I was reluctantly leaving, much chagrined to find that I had waited in vain, I saw, thrown against the window for a few moments only, a curious enlarged shadow of a man’s head. It seemed to wear a kind of tam-o’-shanter, below which was a shade or vizor sticking out beyond the man’s face like the gigantic beak of a bird. A mass of wavy hair and beard showed underneath the cap. Suddenly the shadow disappeared, much to my disappointment, and although I watched in the fog and dampness for half an hour longer, it did not again appear.

I wandered home, puzzled and speculating, but determined that I would wait until morning if I were ever fortunate enough to come across the vehicle again. Weeks passed before the opportunity occurred, and even then, had it not been for a very singular[2] incident, I doubt if I should ever have fathomed the mystery of the curious vehicle.

It was Christmas Eve, the night bit terly cold. I had clothed myself in my thickest ulster. My feet were incased in arctics, my hands in warm fur gloves, and with rough Scotch cap[3] I felt sure I could brave the coldest night. Thus equipped, I started out, and when I returned at midnight in the beginning of a whirling, almost blinding snowstorm, the Christmas chimes were ringing, and the whole air seemed filled with Christmas cheer.

Turning a corner, I discovered the vehicle in the same place and position. This time, as I had before resolved, I would wait until morning if necessary. So I began pacing up and down the sidewalk in front of the vehicle, taking strolls of five or ten minutes apart, and then returning. I walked until I was almost exhausted. In spite of my heavy ulster I began to feel chilly, so I again took refuge in the doorway of a building opposite.

Should I give it up, I asked myself, after waiting so long? I stood debating the question. No, I would wait a little longer; so, puffing my pipe, I shivered, and watched for developments. At last I was about determined that I must go or perish, when suddenly I saw through the blinding snow the shadow of a pair of hands appear at the dimly lighted window, adjusting a frame or inner sash. You can imagine my interest in the proceedings.

Just at this moment a street sparrow, numb with the cold, and crowded from a window-blind by its companions, dropped, half falling, half flying, to the sidewalk directly in front of the window of the vehicle. It sat blinking in the bright rays of the electric light, quite bewildered, turning its little head first one way, then the other. In the mean time the shadows of the two hands were still visible. The sparrow, probably attracted by the light and the movement of the hands, suddenly flew up, not striking the glass, but hovering with a quick motion of the wings directly in front of the window, its magnified shadow thrown on it by the rays of the electric light. Then the bird dropped to the ground. The occupant was evidently much startled by the large shadow coming so suddenly and at such a time of night. The shadow of his hands quickly disappeared, and so did the frame. In another moment the door of the vehicle opened, giving me a glimpse of a cozy and remarkable interior. It seemed, in contrast with the cold and storm without, filled with warmth and sunshine. It was like a pictorial little room rather than the inside of a wagon or carriage. The occupant looked out in a surprised, excited, and questioning way, as much as to say, “What could that have been?” His whole manner implied that he had been disturbed.

This was my opportunity, and, seizing it instantly, I walked boldly to the door of the vehicle, and said, “It was a little sparrow benumbed with the cold, that fluttered down to the sidewalk, where it lay for a moment, until, probably attracted by the light, it hovered for a few seconds before your window, then fell to the ground again.”

I felt the man eyeing me intently, studying me with a most searching glance. Was he in doubt as to my sincerity? Was it a hidden bond of sympathy between us that made him suddenly relent and invite me to enter his vehicle? What else could have prompted him? For my own part, I instinctively felt for the man, without knowing why, a deep pity.

“Please step inside,” he said; “it is cold.”

And so, at last, I was really admitted, invited into the little interior—that little interior which had piqued my curiosity for so long a time. Yes, I was admitted at last, and now had a chance to look about, and to study the general appearance of the occupant as he moved over for me to sit beside him on the roomy, luxurious seat. What a curious personality! He was a tall, raw-boned man of strong character. His soft gray beard and hair made a marked contrast to the dark surroundings. Now I understood the shadow which I had seen thrown on the window for a few seconds. He wore a tam-o’-shanter cap, and beneath it, to protect his eyes from the lamp-light, a large vizor, or shade, which threw his entire face into deep shadow, giving him a look of a painting by an old master. He had on a loose coat of some rough material.

Surely the interior of no conveyance could be more interesting than this. In the front just back of the driver, were two square windows with sliding wooden shutters, and between the two was a little square mirror. Above these was a rod, from which hung a dark-green cloth curtain which could be drawn at will. Underneath was a chest, or cabinet, of shallow drawers filling the entire width of the carriage, with small brass rings by which to pull them out. On top of this cabinet stood several clear glass jars half filled with pure water. There were two or three oil-lamps with large shades hung in brackets with sockets like steamer-lamps, only one of which was lighted. Underneath the seat was a locker. On the floor of the conveyance, along its four sides, were oblong bars of iron, and in the center was a warm fur rug. One side only of the carriage opened. On the side opposite the door was a rack reaching from the window to the floor, in which stood six or eight light but strongly made frames, over which was stretched the thinnest parchment-like paper. The top of the vehicle was tufted and padded. The prevailing color was dark green. In shape it was somewhat longer and broader than the usual carriage. There was a small revolving circular ventilator in front, over the mirror, which could be opened or closed at will, and which could also be used by the occupant for conversing with the driver.

The man arose, and, opening the ventilator, told the coachman to drive on. Meanwhile I enjoyed the wonderful effect of the little interior—its rich gloom, the strong light from the shaded lamp which was thrown over the floor, the bright electric light gleaming through the falling snow into the window on my left.

The night, being so disagreeable, made the interior seem very bright and comfortable by contrast, as the man closed the sliding wooden shutters, separating us entirely from the snow storm without. There was an artificial warmth which I could not understand, and with it all a sense of security and coziness. The stranger’s manner was both gentle and reassuring. We rode in silence over the rough pavement until we reached the smooth asphalt.

Then he began:

“I do not consider myself superstitious, but somehow I don’t like it—that little bird hovering in front of my window. It seems like a bad omen, and it was a shadow which startled me. My life seems haunted with shadows, and they always bring misfortune to me.”

We were both silent for a time, then he went on:

“How curious life is! Here am I riding with you, a total stranger, long past midnight. You are the first I have ever admitted into this wagon, with the exception of my faithful Cato, who is driving. If one could only see from the beginning how strangely one’s life is to be ordered.”

The stranger’s voice was rich and deep. I hoped he would continue so that I might get some idea of him and his peculiar mode of life, and what was going on night after night in this interior. I waited for him to proceed.

“Have you known any trouble or sorrow in your life?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied; “I have lost nearly all who were dear to me in this round world.”

“Then,” said he, “I will tell you my story with the hope that it will be both understood and appreciated. I loved from childhood a charming girl, sweet and pure. I need not go into the detail of all that boyish love, but in my early manhood and her early womanhood we were married—and what a sweet bride she was!

“We lived in an old white farmhouse in a village near the great city—a beautiful place, a long, low, two-story-and-attic farmhouse, probably fifty or sixty years old. How well I can see it—its sloping roof, the extension, the quaint doorway with side-lights and with a window over the top, the front porch with gracefully shaped newels, the long piazza running the entire length of the extension, great chimneys at each end, and enormous pine-trees in front of the house! The house stood on a little elevation, with terraced bank, and with a pretty fence inclosing it. Beyond was an old well with lattice-work sides and door, and a pathway trodden by the feet of former occupants, long since dead. In front of the house were circular beds of old-time flowers—sweet-williams, lady’s-slippers, larkspur, and foxglove. At the rear, great banks of tiger-lilies threw their delicate blue shadows against the white surface of our little home. In one corner of our garden we had left the weeds to grow luxuriantly, like miniature forest trees, and found much pleasure in studying their beautiful forms. How fine they looked in silhouette against the sunset sky! On one side of the old-fashioned doorway were shrubs and a rose-of- Sharon tree, and on the other, honeysuckle and syringa-bushes. There were also many kinds of fruit—and shade-trees.

“How happily we walked up and down the shady lanes of that little village! For us the birds sang sweetly. We took delight in our flowers, and everything about us. In the evening we would enjoy the sunsets, returning home arm in arm in the afterglow, to sit in the cool of the evening on the piazza and to listen to the wind as it sighed through the pines. What music they made for us! We compared it with what poets of all ages had sung of them, and went to sleep, lulled to rest by the wind through their soft boughs.”

He paused again, evidently thinking of the happy time.

“How can I tell you,” he resumed, “of the life that went on in that simple old farmhouse? Our pleasant woodfire on the hearth; a few photographs from the old masters on the walls; our favorite books of poetry and fiction, which we read together during the long winter evenings, while the pine trees sighed outside, and all was so comfortable and cozy within; or the lovely walks in spring and summer, through the by ways of the pretty little village, with its hedgerows, blackberries, and wild flowers. How we watched for the first violets, and what joy the early blossoms gave us! What pleasure we took in those delightful years, and how smoothly our lives ran on! Each day I went to the city, and was always cheered by the thought that my sweet wife would be at the station to meet me. How pure she looked in the summer evenings, clad in her thin white dresses, with a silver fan and brooch, her dark hair and eyes like those of a startled fawn!

“Well, I need not dwell longer on all this. It was only for a few short years, when one cruel cold day about the happy Christmas-time she was taken ill, and grew steadily worse, and all that could be done for her would not save her. She died. I can see her now—her dark hair laid back on the pillow, and the peaceful, happy smile on her face. We buried her beneath the snow, in the old graveyard overlooking the river, and I went home broken hearted.”

I heard the poor fellow sigh, and for a time he was silent as the carriage went on through the snow. “What can be the connection of this queer craft with what he is telling me?” I thought. When he resumed, he said:

“For months I tried to live on in the little house, but life became terrible. In the evenings, as I sat by the pleasant log fire, I would imagine I heard her footsteps on the stairs, and her voice calling me. I did my best to conquer my grief, but it was of no use. The light seemed gone out of my life. At last I could stand it no longer, and I moved all my worldly possessions to another house in the same village. I could not bear to think of going away from the place entirely.

“When the springtime came again, and the lovely flowers were in bloom, and the birds were singing their sweet songs; when the wind breathed softly through the pine-trees, and she was gone, the sunsets were in vain, and all nature seemed mourning. After this I busied myself with all kinds of occupation, but without success. Life became sadder and sadder, until finally in despair I took a foreign trip. I traveled far and wide, but always with the same weary despondency and gloom. The image of my loved one was always with me. Nothing in life satisfied me. I wandered through country after country, looking at old masters, grand churches, listening to cathedral music, but always before me was the same picture—the old white farmhouse, the great mournful pines, and with it all the memory of the sweet life now departed, for which nothing could make amends.”

Then he was silent, and as we drove over the soft, snow-covered asphalt, he became absorbed in thought.

“After a year or so of restless foreign travel I drifted back to my own country and to the little village. Night after night I wandered around the empty house where we had lived, and through the little garden, and would stand at midnight listening to the sad sighing of the wind through the pine-trees, which to me sounded like a requiem for the dead. Many a moonlight night have I stood gazing into the windows, and imagine her looking out at me as in the happy days of old, and I would walk up and down the path thinking, oh, how sadly! of the times we used to return by it from our evening walks.

“Finally the little village became hateful to me. I could endure it no longer, and I shook its dust from my feet. With reluctance I moved away into the heart of the great city, but with the same longing in my heart—the same despair. I hunted up my two faithful black servants who had lived with us for several years. I bought a house in the old part of the city, and there we now live, and I am well cared for by them. Let me read you portions of a letter from her—one of the last she wrote,” and he took from his pocket a little morocco book with monogram in silver script letters. He rose and asked the driver to stop, and turning the light up, said: “This will give you some idea of the sweet life, with its love of nature, that went on in and about that little cottage. The letter was written to me when I was in another city.” He read as follows:

“My dear, I can hardly tell you how lovely the shadows looked as I strolled around our little house this evening, and was filled with delight by their beautiful but evasive forms. To begin with, you remember the exquisite, almost silhouette, shadow of the rose-of-Sharon bush by the front door. I gave it a long study tonight. Its fine, decorative character reminded me of a Japanese drawing, only it is far more delicate and subtle. If this could be painted in soft gray on the door-posts and around the little side windows, how it would beautify our plain dwelling, and what a permanent reminder it would be of our delightful summer days!

“But if I spend too much time on a single shadow, I shall have no room left to ‘tell you of the greater ones we have enjoyed together . . . From the path near the gate, and looking toward the house, I saw tonight, and seemed to feel for the first time, the wonderful tenderness of the great shadow which nearly covers the end and side of our house. How mysterious our kitchen became, with its shed completely enclosed in velvety gloom suggesting both sorrow and tragedy; while the other end of the house was covered with fantastic forms, soft and ethereal, and with a delicacy indescribable . . . But when the moon came up, and the soft shadows of the pines were cast on the pure white weather-boards of our little home,—the shadows of our own pines, the pines we love so well, and through whose branches we have heard music sweet and low, soft and sad,—then I thought of you as I studied their masses tossing so gently, their movement almost imperceptible, and I longed for you as I studied their moving forms, their richness, variety, and texture—for you to tell me of their artistic beauty—your delicate, poetic appreciation of their loveliness. . . . And at last, may the sun and moon shine brightly and cast beautiful shadows among and over the tombstones for you and for me, my dear, and may a blessed hope make the sunset of life glorious for us both.”

When he had finished reading, and had asked the driver to drive on, he became absorbed and silent, and I thought, “How strange to be riding through the streets of the city after midnight in a whirling snowstorm with a stranger, in a vehicle so remarkable, listening to such a pathetic love-story, such a beautiful description of quiet domestic life.” It was a charming idyl.

“You can get an idea from this,” he said, “of the delightful, contented life which went on in the little cottage,” and he sat holding the book in his hands as though he were living it all over again, while the bright silver script monogram gleamed and glistened on the cover until he turned down the light, and for a time we drove over the smooth asphalt in utter silence.

“Do you wonder,” he suddenly asked, “that the shadow of that little bird has caused me uneasiness, and yet do you not see that almost the last letter she wrote me was filled with omens, shadows? It is but natural that I should have some feeling about it—and yet, why should I care? I have only myself and my two old servants who could be affected by it, bad or good. For myself, my only desire is to live long enough to complete my work ; then I am both ready and willing to go. I shall welcome death with delight.”

I had become so absorbed in his story that I had forgotten all about my surroundings ; but now as he paused I again asked myself what strange connection had this sad story, and the letter, and all that he had been telling me, with the wagon; for I was sure that in some queer way the story would help to explain it all.

“While in Europe,” he went on, “I studied the old masters a great deal, particularly the halos and nimbuses surrounding the heads of the saints. I cannot begin to tell you how interesting they became to me. I was struck with the exquisite workmanship bestowed on many of them, but fine as they were, they never came up to my idea of what a halo should be. As my loved one was so pure and gentle, I always thought of her as a saint (and indeed she is such), and I would become interested and imagine what kind of halo I would surround her with if I were painting her—not one of the halos of the old masters seemed fine enough or ethereal enough for her. I had always been fond of art, and had been considered a fair amateur artist. One evening after I had moved to the city, and while riding in a cab (oh, how gloomy!) on a snowy evening something like this very night, I looked through the window down at an electric light, and there I saw the loveliest halo, in miniature. Such tints! A heavenly vision! I thought of the old masters, of the beautiful Siena Madonna, and with sudden joy I thought: ‘Why should I not paint the image of her I love ? Why should I not clothe her in Madonna-like robes, with a halo which could come only out of the nineteenth century? Why should she not have a halo far outshining and far surpassing in beauty any halo ever painted by mortal man?’ I rode nearly the whole night through, evidently to the despair of the driver, as I repeatedly asked him to stop opposite electric lights and street-lamps.

“From that day I had a new purpose in life. I had this wagon built just as you see it. For months I thought of it. Over and over again I drew my plans before the vehicle was actually constructed. Then I began my work. Old Cato, who is driving, sits night after night, unmindful of the cold, wrapped in his great fur coat, and he waits and I work through the mid night hours to conceive and make real the new Madonna.”

What a strange, subtle connection the whole thing had, as he suddenly tapped on the small window and we stopped directly in front of an electric light ! As he opened the sliding shutter I saw, through the frosted window and the feathery snow, such a vision of loveliness—a little halo that could scarcely be described in words. It was like a miniature circular rainbow, intensified and glorified by the glittering rays of the penetrating electric light.

“What could be more beautiful than that? Isn’t it exquisite?” he asked. “Did ever painted saint have a halo like that?”

I held my breath, for I had never seen anything so beautiful.

“I have worked at it for a long time. I have not yet accomplished it, but I hope to. I am coming nearer to it every night in which I can work. There are not many during the winter; the conditions of atmosphere and temperature must be just right. On foggy nights, or when the air is filled with light, flying snow—these are the nights in which the little halos glow around the electric lights, street-lamps, and lights in show-windows. Oh,” he said, “they fill me with a happiness and delight I cannot describe, as I try all kinds of experiments to transfix the beautiful colors of their delicate rays!

“Let me show you,” he went on, and he lifted one of the frames which I have already described, covered with a thin parchment-like paper. This he care fully buttoned to a groove in the window. On the surface of the stretched parchment the little halo glowed with its prismatic tints, and again I held my breath at the beauty of it. I too was becoming a halo-worshiper. Then he lifted from the rack on the side, and held up to the light, first one and then another of the frames on the parchment surface of which he had actually traced with lines of color, against the gloom beyond, radiating lines crossing and re-crossing, glowing with rainbow tints seen through and against the window.

“Do you know anything of Frankenstein’s wonderful Magic Reciprocals, sometimes called Harmonic Responses?”[*] he asked. “How I longed for his marvelous power, so that I might experiment with them. But they were far beyond my skill, and also, perhaps, too scientific and geometrical for my purpose; and so I was forced to discard them and begin afresh in my own way. I have had reasonable success, although I have not yet reached the purity of color nor the brilliancy that I wish. I do not know that mortal man ever can. I have tried all sorts of experiments—lines of silver crossed with lines of gold; prismatic threads of silk; and now I have abandoned them all, and beginning again, perhaps for the fortieth time. But if I am only able to do it, nothing can give me greater happiness. I can close my eyes in peace at last.” After he had shown me his experiments, he removed the little frame from the window, closed the sliding shutter on the side, and, turning the circular ventilator, asked the driver to drive on.

“Now for an extended view,” he said, and he opened the shutter of one of the front windows, and then of the other on each side of the mirror. What a vista of loveliness! A long perspective of glowing halos, vanishing down the street through the flying snow, until they were mere specks of light in the distance. The whole atmosphere was filled with circular rainbows, and again he dwelt on their beauty. They glowed with ultramarine, with delicate green, with gold and silver, and like light from burnished copper, and our little vehicle seemed a moving palace of delight, as we drove on through the blinding storm. Turning into one of the narrower streets, away from the electric lights, we saw the long line of receding gas-lamps, each with its softly subdued nimbus, and he said in a low and gentle voice, almost a whisper, “The street of halos.”

When he had closed the shutters again he said, “Let me show you my cabinet of colors and working tools.” He pulled out a shallow drawer, and there on small porcelain plaques (the kind used by water-color painters) side by side, in regular order, was every shade of red, from the faintest pink to the deepest crimson. He opened the next drawer, and instead of the red was an arrangement of blues, from delicate turquoise to deepest ultramarine. In the third drawer was an arrangement of yellows, running from Naples to deepest cadnium.

“I deal in primary colors,” he said, “for what would you paint rainbows in but red, blue, and yellow?”

Then he opened the fourth drawer, and there, laid with precision, were long-handled brushes from the finest sable (mere pin points) up to thick ones as large as one’s finger. There were flat ones and round ones, short ones and long ones. As he opened the fifth drawer, “For odds and ends,” he said.

This was a little deeper than the others, and in it were sponges fine and coarse, erasers, scrapers, and boxes of drawing-tacks of various sizes. In the last drawer were soft white rags and sheets of blotting-paper of assorted sizes.

After he had shown me the contents of the cabinet, he said, “I have been quite disturbed by the shadow of that little bird. Will you join me in a glass of old sherry?” He opened the locker underneath the seat, and brought out an odd-shaped bottle, which he unscrewed, handing me a small, thistle-shaped glass and a tin box containing crackers.

“It is a bad night,” he said; “a very bad night. I feel it, even, with the warmth of this interior. Those long bars of iron are filled with hot water, which usually keeps me very warm.”

Then he passed through the ventilator, to the driver, some crackers and sherry. After he had closed it, and put away the bottle, box, and glasses, we both mused a long time, the halo-painter completely lost in reverie, and I thinking of the undying love of such a man—a man who could love but one and for whom no other eyes or voice could ever mean so much. With him love was an all-absorbing passion. He had given his heart without reserve, and for him no other love could ever bloom again. I thought of him sitting, night after night, in his solitary vehicle working at the halo—the new halo which should surround the head of her he loved. I thought of him in the lonely early morning hours, working at a nimbus which was far to outshine in beauty and delicacy of any painted or dreamed of by God-fearing saint-painters of old.

He opened the shutters, and the light from the lamp began to grow dimmer as the early morning light shone faintly through the windows. I noticed the deep furrows of care and sorrow which marked his strong, pathetic face, purified by suffering and lighted by divine hope—the face of one who lived in another world, and for whom all of life was centered in his ideal—one who was in the world, but not of it.

As he bade me goodbye, his face beamed in the early Christmas morning light with indescribable tenderness; and as the little wagon with its faithful old black driver disappeared through the snow, I thought again and again of the beautiful, touching love of the man who would sit night after night trying to realize his dream of beauty, to clothe in the garb of a saint the form of her he loved.

Alexander W. Drake (1843–1916)

_____________________________

1. A buffalo-robe (buffalo robe) is a one-piece garment made from cured buffalo hide with the hair left on. In addition to using them as a wrap-around form of clothing, Native American Indians also used buffalo robes as blankets, and as saddles for their horses. Between the 1840s to the 1870s, the commercial demand for buffalo robes in US cities became so high that it almost resulted in the extinction of the buffalo species.

2. The word singular can be used in several ways. In the context of the story, it indicates something that is unusual, odd, or peculiar. [Singular @ Merriam-Webster]

3. Scotch cap is another name for the tam-o’-shanter.

* “The Magic Reciprocals or Harmonic Responses, were discovered by Gustavus Frankenstein, and are properly drawn in color. The following are extracts from letters received from Mr. Frankenstein, to whom the author is indebted for the drawings at the beginning and end of this story: “To-morrow morning I shall send them. They are transcendently lovely. They are halos, if ever there was a halo. So wonder fully magical are they that I think thou wilt modify thy language, and perhaps say that Frankenstein produces halos almost, if not quite, to the very perfection. Why, they seem to dazzle and bewilder like the very sun itself. They do not actually emit light, but they look like the soul of light. More like beautiful thoughts are they, spirits of loveliness, than like any thing tangible.” … “I was a long time working out the mathematical problem of the perfectly balanced and completely symmetrical circular harmonic re sponses ; and then the drawings were executed with the greatest care as to perfect precision and accuracy.” . . . “The little round white spot in the center imparts an animating expression to the whole Response; and now, as I write, it occurs to me very forcibly that the whole Response looks something like — and very much like — the iris of the eye, and the little round spot in the center is the pupil. If the iris were all iris, having no pupil in the center, it would appear expressionless and not vividly suggestive of the soul of life. The spot in the center may be looked upon as the tangible exist ence or thing which is the source of the surrounding halo.” Again : “The true and complete Response — the mathematical assertion — has the animating spot in the center.” [The preceding text is taken from the original footnote at the bottom of pages 63 to 64 of the print copy of Three Midnight Stories by Alexander W. Drake, from which “The Curious Vehicle” is taken. It appears to reference a text written by the German-American painter, mathematician, author, and drawing teacher Gustavus Frankenstein. The text was called Magic Reciprocals. Little information is available about it online. However, a record at The Library of Congress proves its existance: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010647050/marc/]

_____________________________