From the Pit by Adam Hull Shirk

Overlooked by editors putting together horror story anthologies, From the Pit only appears to have been published once, in the May 1927 issue of Weird Tales. At just over 9,000 words long, it’s a novelette, not a short story, so if you want o want to read From the Pit in a single sitting, you will need to set aside around 40 minutes to an hour to do so. However, the story is split into two parts, making it easy to read in a couple of short sessions.

A story that combines elements of terror and romance, From the Pit is, in my opinion, one of Shirk’s best stories, and I find it surprising it does not appear to have been reprinted.

About Adam Hull Shirk

Adam Hull Shirk (1887–1931) was an American author of plays and short stories. The horror film The Ape (1940), starring Boris Karloff, was based on Shirk’s play of the same name. Shirk also wrote the script for Ingagi (1930), a fantasy horror / adventure film set in the Congo jungle.

In total, Shirk is associated with 8 films, including Nu-Ma-Pu Cannibalism (1931) and House of Mystery (1934), but it’s generally unclear if he had a hand in writing the scripts or if other writers adapted his work.

Unfortunately, there is not much information available about Adam Hull Shirk. However, between 1923 and 1927, he sold five stories to Weird Tales magazine, including “Osiris” and “Mandrake“, both of which were published in 1923.

From the Pit

by Adam Hull Shirk

(Online Text )

I

The note from my Uncle Carl did not imbue me with an excess of emotion despite its conciliatory, not to say appealing tone:

“My Dear Nephew?

“I need you at once and I hope you will forget any past differences and leave at the earliest possible moment. I enclose more than enough for expenses of trip. For God’s sake come!”

The last sentence had been scribbled in pencil at the bottom of the typewritten communication and suggested an access of some emotion approaching fear. The address was new, for my uncle, Carl Brand, had always resided in Chicago, where his eminence as a surgeon was continually referred to in the press. Now, apparently, he had removed to Wychington, Illinois, which I ascertained by reference to the local railway office was some forty miles from the metropolis.

I considered whether to return the money or accede to his request. I recalled somewhat bitterly his coldness when, on the death of my dear mother, his own sister, a few years before, he had done no more than send formal condolences, though he knew we were in very straitened [1] circumstances at the time. Again, a few months afterward, when I asked his assistance in obtaining a position in Chicago, he had advised me coldly enough to stay in Nevada. I had done so and by dint of hard work made myself a good berth with the Carson City Mercantile Trust Company. I thought it all over and finally came to a decision. After all, he was my only living relative. If he was in need, I could not refuse. So I obtained a leave of absence, packed a grip [2] and took the train for Chicago. Arriving there, I found that a branch line stopped at Wychington, arriving around 9 o’clock in the evening.

The station, when the slow traveling train at last set me down there, was lighted by a single electric bulb and was already closed. Luckily it was a warm, clear night in the spring, so that walking would be no hardship, and certainly it would be necessary to walk, for there were no conveyances in sight. I had not wired Uncle Carl of my coming; I did not anticipate any difficulty in finding so distinguished an individual in a town of three thousand population where, most likely, everyone knew his neighbor’s business.

The town was visible in the early moonlight, in a little valley below the tracks and some hundreds of yards distant. A few lights were visible, but quite evidently this was a “9 o’clock” village and only a garage or drug store would probably still be open. It was in the latter, attended by a sleepy-eyed clerk, that I put my inquiry regarding the whereabouts of Dr. Brand. He looked at me in some surprize and answered my question, but asked one of his own at the same time.

“You’re a stranger, aren’t you? He’s living over at the old Raynes place.”

Further inquiry elicited the information that the old Raynes place was the dilapidated and formerly untenanted mansion at the fringe of woods on the other side of the town. It appeared that my relative had rented it, and partially repaired the damage it had sustained through the years of emptiness, some three months before.

The clerk vouchsafed one more bit of information as I left the store: “Better sing out before you ring the bell—he’s kind of queer, you know.”

I didn’t know, but could well suspect it. However, I followed the advice and “sang out” after I had reached the dark doorway, following a difficult passage through a tangle of weeds and shrubbery to the veranda.

It was an old house, almost hidden by the encroaching woods; it was, furthermore, in a sad state of disrepair which was apparent even in the kindly moonlight. Evidently Uncle Carl’s efforts to restore the place had not extended beyond its interior.

I stood before the door; not a light was visible, not a sound came from within. I called loudly: “Uncle Carl—this is Tom Ranee—are you awake?”

Then I rang the bell.

My friend the clerk, however, had been quite sound in his advice, for even as the bell was jangling discordantly somewhere in the bowels of the old house, the door opened and a queer face peered out. I say “queer” advisedly. That it was my uncle’s I had no doubt, but I had never seen him and was scarcely prepared for the vision. He was attired in a dressing gown of faded brown; his shock of white hair was leonine and unkempt; his face was gaunt, rugged and forbidding, while his frame, despite the indication that he was a man well past fifty, was still powerful.

“So you’ve come, have you?”

The greeting, in a deep, sonorous voice, was hardly what I might have expected, but I decided to take things as they came and answered affirmatively.

“You are my uncle?” I asked, somewhat superfluously.

He growled out a reply, also in the affirmative. “Come in,” he added, and swung the door ajar, at the same time switching on a light that revealed a hallway with a worn carpet and the woodwork black with age and grime.

My uncle led me to the living room—a large apartment, furnished with a certain degree of comfort. He sank into an easy chair and nodded me to another. A center table, littered with books and papers, mingled with certain scientific instruments, occupied a considerable part of the space.

“You were already in bed?” I asked.

“No,” he answered; “I had switched off the light and was dozing here in the dark. But I’ll show you to your room presently. I suppose you are tired.”

“Not especially. I’m anxious to know why you sent for me; why you’re living here instead of in Chicago: are you all alone?”

“I am almost alone,” he admitted. “My secretary, Miss Darling, comes here every day to take dictation. I brought her from Chicago. I have no relatives besides yourself. I came here to finish a—a work on which I am engaged.”

“Oh, I see. And why—?”

“I sent for you,” he continued, as if I had not interrupted, “because I believe I am in danger; I need a man I could trust. I hope I can trust you?”

The observation was almost interrogative and I smiled.

“I hope you can; I didn’t bring any credentials,” I said, “but my record is clean where I come from.”

“Tut-tut,” he retorted; “quick-tempered, like your mother. Well, it’s all right. I haven’t been particularly considerate, I know. Perhaps you will not regret coming, nevertheless—but we can go to bed now. In the morning I’ll tell you all—all that you need to know.”

His hesitancy, the hint of danger, of menace, rather stirred my somewhat sluggish imagination. Perhaps I should really enjoy this adventure after all. He said one thing more before showing me to the small but comfortable room where I was to sleep.

“I hope,” he said, “you brought a revolver with you. Keep it handy, if you did. I sleep across the hall—if you hear anything, call; if you see anything—shoot first and ask questions afterward.”

“But what—?”

“I can’t tell you now—wait!”

He ambled off, and I heard the door close and a key turn in the lock. I was realty tired, in spite of my disclaimer, and in ten minutes I was asleep—nor did anything disturb my rest until the sun breaking through the windows aroused me. I looked at my watch; it was 9 o’clock, and I dressed hastily, making my toilet in the adjoining bathroom. Then I descended the stairs, lured by a sound that was incongruous after the aspect of my uncle and his abode had become firmly established in my mind. It was the voice of a woman—singing!

The owner of the voice I encountered in the lower hallway as I rounded a turn, and both the song and the singer stopped abruptly.

“Oh,” she said.

I was conscious of an aureole of golden curls, a piquant [3] face and a trim figure in a light-colored dress.

“I beg your pardon,” I said, “you must be Miss Darling; I am Tom Ranee, Dr. Brand’s nephew; I came last 1 night.”

This information I blurted out in a single sentence, hastily, lest I frighten away this vision of loveliness, like a butterfly in a barracks. The colors had departed from her face at the sudden encounter but flooded back again, rendering her far more lovely. She nodded in comprehension.

“My—Dr. Brand—told me you might come; I didn’t know, of course —I am very happy to meet you.”

She extended one dainty hand and I took it gratefully. Oh, yes, I decided, this would be an interesting adventure! I may perhaps expose a somewhat precipitate nature when I admit that already at first sight I was half in love with this girl—I who had been heart-whole and proof against the sex during my twenty-five years of life. . . . She was exquisite—there is no other word—delicate yet not of the fragile type; her eyes were a cornflower blue, and sincerity and wholesomeness were evident in their clear glances. I wondered what her first name might be.

“Dr. Brand is in the dining room; he has just started breakfast; you can join him.” She nodded toward the door.

“Do you mean to say that you cook for him ?’’

She laughed ripplingly: “Oh, yes; I’m cook and secretary all in one. I run over early and get breakfast, and before leaving in the evening I get dinner. We skip lunch,” she added whimsically.

I could not fathom it! This delicately beautiful girl who would have been the cynosure of all eyes on Michigan Boulevard or Fifth Avenue, satisfied to live in this out-of-the-way hole and to cook and slave for this queer old uncle of mine. It was too much to understand all at once. Perhaps, I reflected, he paid her well—or possibly he had rendered her a great service which she was trying to repay. I remembered he was a doctor—and a famous one. Well, I should learn all later on. Meanwhile a healthy appetite lured me to the dining room where Uncle Carl was ensconced behind a paper. He laid it down as I entered and nodded grimly.

“All quiet last night,” I ventured, after the good-mornings were said.

“I am afraid,” he returned, rather caustically, “it would not have troubled you had the house been struck by lightning.”

I laughed sheepishly. “I was more tired than I thought,” I said in extenuation.

“After breakfast,” he declared, “I’ll tell you something more about my reason for bringing you here.”

I ate for a space in silence. Finally I made another venture.

“ I just met your secretary,” I observed, quite casually.. “Miss Darling, isn’t it? She is charming.”

He looked at me for a moment with a cold and calculating gaze. Then he nodded and grunted a single word: “Humph!”

After that I desisted and we devoted our attentions exclusively to the viands which had been placed there by Miss Darling, who did not put in an appearance, much to my disappointment. Evidently she dined alone in the kitchen, probably, I decided, of her own volition.

The meal completed, Uncle Carl led the way into the living room and motioned me to a seat as before.

“I’m not going to disguise the fact,” he said, abruptly, once the door was closed, “that I am living in dread of an attack; and that I sent for you because I need a strong arm in case of danger.”

“What kind of attack?” I asked with almost equal abruptness. I was thinking that he was rather careless in subjecting a delicate girl like Miss Darling to such a menace, and it made me cool toward him.

He hesitated a moment. “I cannot tell you that—at present—except that I mean a physical danger—combined with a mental one.”

“From a man, or men?”

“I—I don’t know!”

“You don’t know?” I echoed his words. “I don’t understand.”

“I don’t expect you to do so,” he retorted. “All I ask is that you aid in case of—the need arising.”

“And Miss Darling?” I could not help asking.

“Is well able to take care of herself.”

“You mean she knows?”

“As much as—you do.”

“But not,” I said, shrewdly, “as much as you know?”

He did not answer. In fact he sat listening intently, and although I followed his example I could detect no untoward sound; indeed the only sound was one that brought joy to my ears—the voice of the girl, singing again. I looked at my uncle’s face for some softening, but there was not the slightest relaxation in the hard lines of his craggy features, which now, by daylight, were more rugged than in the artificial light of the night before.

“Well,” I said, finally, “what do you want me to do, now I’m here? How long do you wish me to stay?”

“I want you to keep on the alert, always,” he said, coming quite suddenly back to normal after the strained attitude of listening. “Have your gun handy; at night especially, I want you to help me keep watch. We will divide the time in equal parts and alternate. Tonight, for instance, you will retire at 9 o’clock and arise at 1. I will then retire.”

“But I don’t understand—watch for what?”

“For anything unusual that may occur. It may come in any form.”

“What?”

“The danger. It may come at night; it may come in the broad daylight; it may come from within or from without. Or it may never come at all.”

“Then how long do you wish me to stay?”

“Until it comes, or else until I learn by some other avenue that the danger is past. I can’t explain, and if I did you wouldn’t understand, Tom.”

It was his first use of my given name, and somehow it warmed me toward him. I began even to feel a trace of pity for this strong man, this man with a record for high achievement in the world of science, hiding away here almost in the wilderness from a nameless dread. Then my thoughts went back to the girl.

“Who is Miss Darling?” I asked quite suddenly.

“Ah,” he said, with a flicker of interest in his cold eyes. “You seem unduly interested in the young woman.”

“How could I help being?—it is so odd, her being here at all and cooking—why, she could be—”

“How do you know what her motives or wishes may be?” he began almost angrily, but softened at once. “Listen, my boy,” he went on, “I saved her mother once when she had been given up to die—by means of a simple operation. Five years longer she was able to keep her with her, and she has never forgotten. They were poor and I asked no fee. She would give her life, I believe, for me.”

It was as I had suspected. Yet I could not get over the feeling that he was exacting rather heavy tribute now for a charitable deed in the past. However, it was too early to make decisions; later she would perhaps tell me herself. I let it go at that and recapitulated.

“Then,” I said, “you want me simply as a bodyguard; I am to keep watch at certain times by night and all the time by day. And you will tell me when I am relieved.”

“That’s it,” he agreed. “As to your work—I do not know under what circumstances you left, but I will say this—no matter what the outcome of this affair; no matter what happens to me—you will never have to work again unless you want to.”

It was generous and fairly took my breath away. I could only say “thank you,” but after a moment, I added: “Count on me, Uncle Carl. I think you will understand that my having come as I did proves I had no such expectations; I felt it my duty in spite of what—”

“Yes, yes, I know,” he interrupted, hastily. “It is all right.”

“Well, then,” I insisted, “if I’m to be of any real help to you, give me some suggestion of what form this danger may assume—of what I shall look out for.”

“I told you—” he began, but I would not be put off thus easily.

“I am no child,” I exclaimed. “Tell me something at least—is it man or woman?—young or old—?”

“It may be neither,” he began, impressively. “I mean—there is something I can’t explain. There may be one—there may be two—one I can deal with—the other—I don’t know.”

“Uncle Carl—what do you mean?”

But he only shook his head grimly, and turning, stalked abruptly out of the room. Was he mad? The thought flashed across my mind, but I rejected it when I remembered the girl. I went across and raised the shade from the window, which looked out upon a tangled mass of flowers and weeds, once a garden, now gone to seed. And among these disordered shrubs a form was moving—that of Miss Darling. I opened the sash with difficulty and the noise disturbed her. She looked up with a startled smile.

“Did you have a nice breakfast?” she asked.

“Heavenly,” I replied. Instantly all thoughts of my uncle and his peculiar crotchet [4] vanished from my mind. She was there, the morning was beautiful, the sun played in her hair and turned it to spun gold; the flowers became enchanted blossoms, the tangled, garden a king’s pleasance.

“Wait,” I called, “I’m coming out.”

I shut the window and hastened around to the door, and a moment later stood beside her awkwardly in what had become a shining field of Arcady.

“Miss Darling,” I said, “please tell me your given name—somehow I feel that I simply must know it.”

She laughed at me, white teeth and red lips forming a combination that was irresistible. Dimples played in cheeks that bloomed with health and youth; the soft wind caught the tendrils of her golden hair and blew them distractingly across her broad low forehead.

“My first name is—Vida.”

“Vida Darling—what a wonderful combination!”

I must have betrayed my feelings, so close to the surface, for she flushed and turned to the flowers in which she was apparently working, trying to bring a bit of order from the chaos of neglect.

“Are you—happy to be here?” I could not help the question.

She looked at me again, seriously enough.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I owe him so much—and there are things I don’t understand. Perhaps I’m not quite myself at times—I forget some things …. others I remember. Yes—I’m happy enough, and”—she hesitated and then smiled adorably—“I’m glad you’ve come—you are strong and you—you can help.”

“But what is this danger?”

“I—I can’t explain.”

Always that phrase—both from my uncle and this girl: “I can’t explain.” Well, I told myself, I would do my best to find out what they had so much difficulty in explaining.

II

Three weeks of what appeared to be senseless precautions preceded the events which culminated in the strange solution of the puzzle of my uncle and his beautiful secretary.

Between watching at night and by day, I still found ample opportunity of cultivating Vida Darling, and rather to my surprize I found that my uncle made no effort to discourage a growing intimacy which could lead but to one conclusion.

Exactly three weeks from the day when I first heard her singing, I asked Yida to become my wife—and she consented. I could hardly believe it myself. It was strange enough that so attractive a girl, who, it seemed to me, possessed all the virtues, could have gone on so long without having been captured by someone. Perhaps, I decided, she had lived a secluded life. I knew she was an orphan, had had a convent education and four years before had come to my uncle. Three years before that had occurred the operation on her mother which had restored Mrs. Darling to health. So, according to Uncle Carl’s words, she had been an orphan for two years. She was, as she told me, twenty-five. Although about my age, she seemed much younger than I was. Perhaps it was her innocence, her sweetness, her general air of girlishness which kept her almost a child. My good fortune in winning her promise to become my wife was still dazzling my senses when the first untoward event occurred to mar what had become an idyl for me, even if it was a nightmare to my uncle.

It was the night of my late watch—that is, I went on duty at 1 o’clock and served till daylight. It was our custom to sit in the living room, with the door to the hallway wide open, thus commanding a view of the stairs leading to the bedrooms above. A fire in the grate made it cheerful in the big room with its littered and over-large center table. I kept my automatic at my elbow, with a dish of sandwiches flanking the weapon. Also there was a spirit lamp on which I could heat coffee to keep me awake. With plenty of books and papers, this had become quite a pleasant job, if monotonous. At times I wished something would happen to bring matters to a head. There were several reasons why I wanted to have it over and done with—not the least being that marriage between Vida and myself could hardly be considered until the trouble, whatever it might be, was at an end. Honestly, I don’t think my uncle’s promised financial reward for my services occurred to me. I would have been willing to go back to Nevada and work like a dog to keep Vida beside me and happy.

Some of these thoughts chased themselves through my mind that night as I sat in the living room trying to read but finding it increasingly difficult to keep my mind fixed on the printed page.

I wondered just how much Vida knew about the matter. She had told me nothing more, despite our compact and our love. If only the conventions would have permitted her to share some of those long hours with me, what a heaven it would have been! Just to have seen her sitting under the shaded glow of the reading lamp would have been the greatest joy I could conceive. Well, some day—soon, I hoped—this would come to pass—when she was my wife!

It was while this sweet dream was passing through my mind that I first heard that intermittent tapping, as of someone with a walking stick, coming slowly along a frosty road. But I doubted if it was caused by anything of the sort. It was so regular—almost like the drip of a faucet. Indeed, at first I believed that it was something of the kind; then I discarded this idea because the sound was coming nearer and nearer!

Tap-tap-tap!

Yes, it was nearer, almost at the porch, it seemed. Then it suddenly ceased, and the silence of the waning night was unbroken save for the distant crowing of a cock greeting the approaching day.

It was pitch-dark as yet; through the window, from which the curtain was drawn and the shade raised, I could see only the reflection of my own lamp and the room, of myself seated by the table; the odd optical illusion which everyone has noticed and which in times gone by suggested the famous “Dr. Pepper ghost illusion” which startled even the scientific world.

I strove to penetrate this, but without avail. It came to me uncomfortably that while exterior objects were invisible to me, I was plainly apparent to whoever or whatever might be without. I wished the shade had been drawn. But I made no move. If something were about to happen—

And at that moment came a guarded knock at the door!

I am afraid that my hair rose stiffly on my head; I know that a chill ran down my spine and that involuntarily I seized the butt of the revolver. Something in its solid coldness reassured me and I dropped down upon all fours, still holding the weapon. I did this to escape my position of high visibility through the window. Once beyond the range of the aperture, I rose to my feet and noiselessly crept into the hall. My uncle’s orders had been to arouse him at the first sign of danger. But how could I do so without also alarming the visitor—whoever it might be? I decided to do my own investigating, for the time being at least. Any unusual sound, I knew, would bring Uncle Carl, always a light sleeper, down at once.

I reached the door, and with my revolver ready, the ancient chain fixed in position, opened it a crack.

“Who’s there?” I whispered.

But the vision that confronted me in the darkness of the doorway, but slightly relieved by the radiance from the inner room, caused me hastily to detach the chain and swing the portal wide. Vida stood on the threshold!

Pale as a ghost she was, with an expression distorting her features that was utterly alien to them, an expression of diabolic hate, which gave place to fear and then faded as she fell forward, a dead weight, in my arms. As she did so I noted a long, dark rod or staff which she held clasped in one hand. This clattered to the floor. After all, it had been the tapping of this which I heard. I carried her to a chair. My uncle, aroused, was coming down the stairs and in a moment stood beside me. His eyes fell on the stick. He picked it up gingerly, looked at it for a moment and placed it carefully in a bookcase by the mantel.

“Vida,” I whispered, “what is it?”

She was coming out of her faint and presently opened her eyes sleepily—and smiled! Then suddenly she sprang to her feet.

“Where am I?—oh, my God!—I—”

She saw my uncle and then her eyes turned to mine again and the fear departed from them.

“I must have been sleep-walking.”

Yet she was fully attired; perhaps she had dressed while in a somnambulistic condition.

“Don’t you recall anything?” asked Uncle Carl.

She shook her head. “No. For a moment, when I first awoke, I thought I had a hideous memory, but it must have been a dream—it’s all gone now.”

“It is what I had dreaded,” muttered my uncle, and then got the stick from its place.

“Tell me, Vida, do you remember this?”

He held it before her and she essayed [5] to take it, but he drew it away.

“No,” she answered, “what is it?”

“Nothing—I—” He paused.

“You will have to stay here now, my dear. Mrs. Burns will probably never miss you at the house where you’re staying. And it is nearly daylight. If people wish to talk—they’ll have to talk, that’s all!”

He replaced the stick and locked the door of the bookcase carefully.

Like one in a dream, I had listened to all this and failed utterly to make sense of it. What had the stick to do with it? Why had Vida come here?—in her sleep, if that was it—and why that concentrated hatred in her face when she first arrived? Was it for my uncle? for me? I dismissed both conjectures as absurd.

We spent the remaining hours of darkness together, Vida curled in the big armchair by the fire, sleeping peacefully as a child; my uncle and I, silently smoking and listening. But nothing more occurred and the sun’s rays at last slanted through the windows and chased away the last vestige of the night.

Vida, awakened by the sun, rubbed her eyes and sprang up. Memory returned quickly—memory of her experience only from the moment of her awakening in the room. All else had been blotted out.

“I’ll get breakfast,” she said, and vanished in the direction of the kitchen.

Uncle Carl said no more of the matter to her; but to me, while she was busy preparing the morning meal, he said, “I think matters are coming to a head.”

“How?” I asked vacuously.

“This is the first genuine proof that he—that it might reach us, no matter what safeguards are established. The dread of this has weighed upon my shoulders for months—perhaps it is better that it has come to this.”

“Uncle Carl,” I said, “please tell me more—how can I help, if you keep me in complete ignorance?”

He looked kindly toward me; indeed, of late, I had begun to believe that his severe exterior covered a heart of gold.

“I—do not know what to say beyond what I’ve already told you of this menace. To explain all would take too long—and it may not become necessary. You love Vida, of course.”

“Indeed, yes; I meant to speak to you; she has promised to marry me if all goes well; that’s why I’m so anxious, too. I mean, in addition to my desire to serve you—”

He smiled at my impetuous, schoolboy speech.

“It is well. She loves you, I am sure. Well, if anything happens to me—shield her against anything that may occur. Do you promise?”

“I swear it,” I responded fervently.

“Good. Now be on your guard—I have an intuition that tonight may be the crisis—there may be one, there may be two—”

With this enigmatical sentence, he turned away and left me standing, my mind filled with thoughts that I could not define even to my own satisfaction.

Breakfast over, we all three went into the living room. To keep her mind occupied as well as his own, Uncle Carl gave Vida some dictation on his text-book—a labor of years, evidently—and I went out in the yard and walked through the tangle of shrubbery, wondering what to do, arriving at no conclusion.

The day passed slowly and night fell. Vida had decided to defy the conventions for the occasion, at the earnest desire of my uncle, who confided to us both his fears of some sort of attack that night.

“I would rather you were here—after what occurred last night—than that you should be absent. We must be ready—and together—when the blow falls.”

Vida bowed her head in acknowledgment of the wisdom of his decision.

“You take the spare room,” he said to her, “and Tom and I will watch here in the living room.”

And this arrangement was carried out. At 10 o’clock, Vida went to her room and bade me a sweet good-night as we parted at the foot of the stairs.

“Remember, dear,” I whispered, “that nothing shall harm you while I live to guard you against the world.”

“I know,” she breathed; “good night!”

I went back to Uncle Carl and we put out the lights at his suggestion.

“I want to draw their—his fire,” he explained. “I want it over and done with at whatever cost.”

As we sat in the darkness, I tried vainly to distinguish his features, but without any degree of success. He was simply a blur against the dark shadows of the room. I had my flashlight at my side, the pistol also was ready. Uncle Carl, too, was armed.

The hours dragged by silently, measured by the ticking of the clock which pealed sonorously at the half-hourly intervals. It had just finished striking 12 when a sound broke the stillness—an unwonted sound as of someone or something stirring on the veranda without.

I felt rather than saw Uncle Carl move slightly, tensing his muscles, as did I, so I knew he had heard it, too. But neither of us spoke.

It came again, that furtive, slithering sound; one could hardly call it the sound of footsteps.

And then came a sudden gust of wind—I had not before noticed that it was blowing—the hall door, the main entrance, was open. And then I knew that, purposely no doubt, Uncle Carl had left it unlocked.

“Get ready,” he breathed.

Something was coming into the hallway—I felt again that inrush of air, and it seemed like the wind off a desert, hot and uncanny. And then the darkness of the doorway to the living room was rendered even darker by a black something that filled it.

“Lights!” called Uncle Carl.

I snapped on the flashlight, directing its rays toward the door; at the same instant he switched on the room lights.

What I saw I find difficult to describe, even now, after the passage of years. A man stood in the entrance, wrapped in a black cloak. He was tall and spare [6]. His cloak muffled all but the eyes—eyes that seemed to emit a radiance of their own, like twin streaks of green fire. And behind him loomed another shape, grotesque, dark, heavy and clumsy. It seemed somehow impalpable, so much so that then, as now, I could not determine whether it was shadow or substance. Yet it moved, I swear, separately and apart from the other figure. And I was conscious of a fetid odor, of that warm, sickening air.

“Where is she?” A dull, inhuman voice boomed from the first figure.

“Where you will never get her, you devil,” screamed my uncle, and at the same instant he fired.

I followed suit as the figure lurched into the room toward him. The thing in the background seemed to grow and envelop us all for an instant but my uncle screamed to me wildly: “Tom, Tom—come beside me—here.”

He was muttering some incoherent words, like an incantation, as I took up my stand beside him; and then the cloaked figure—seemingly unhurt by our fire—was upon us. The other intruder, as my uncle continued speaking in what seemed a foreign tongue, receded until it crouched, a black blur at the entrance to the room. The first figure, obviously human, whatever its companion might be, seized Uncle Carl, and as the cloak slipped from the face I saw a hideous countenance, seared as with fire, almost featureless, but cruel as hell. It wound long arms about my uncle, who seemed to have become suddenly a helpless prey to the onslaught. He seemed exhausted as by some tremendous mental effort. Not so, however, was I affected. I pumped my automatic, and as I did so was conscious of a woman’s scream. Vida!

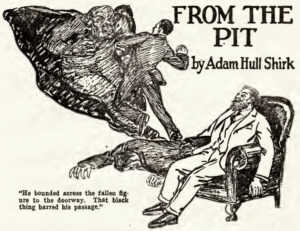

At last my shots had taken effect. The creature with the face of horror reeled and relaxed its clutch, and Uncle Carl, released from the hold, slipped into a chair, unconscious. The figure fell in a heap and I bounded across it toward the doorway. I could hear Vida’s screams, and that black thing barred my passage. I can not describe it; perhaps there are no words in our vocabulary that are equal to the task.

I heard Uncle Carl, roused from his momentary stupor, call out: “Wait, Tom, wait!”

I paused for an instant, and again I heard him repeating that formula of words which now sounded like Latin phrases, but none that were familiar to me. And as I live, before me that dark, unclean thing receded, dwindled, vanished! The strange odor, the hot breath, vanished with it and in a moment I had passed into the hall, and Vida, crumpled in a heap at the foot of the stairs, was held tightly in my arms. Thank God, she was alive.

I turned and saw my uncle stooping over the man on the floor.

He rose from his position with a look of such relief on his face that I breathed a prayer of thanksgiving.

“It’s over,” he said. “He’s dead. Take Vida into the dining room—there’s nothing to fear now—and come back here.”

I did his bidding. The girl was again unconscious, but breathing regularly. I placed her on a couch, which incongruously stood in the dining room, and covered her over carefully, for she was in her nightdress. I turned the lights full on, closed the door, and came back to the living room.

Uncle Carl was standing looking down at the huddled form on the floor. He looked up at my approach and motioned me to come nearer.

“There lies the greatest fiend that the present century has produced,” he said. “He is dead. I do not know which of us killed him. But in any case, I will shoulder all the blame.”

“There can be no blame,” I interposed, “for they came like thieves in the night—it was our right to defend our property and our lives against marauders.”

“Right,” he admitted. “You say ‘they’!” He paused and looked keenly into my face. “You, too, saw—the other?”

“The other man?”

“It was no man,” he replied; “it was nothing for which we have an accurate name. It no longer exists—it was what I can only describe as a ‘familiar’.’’

I shook my head. The term was one with which I had no acquaintance.

“It is a long story and you shall have it all now,” he went on. “But first, we must dispose of this body—and in the morning we will see the authorities. How is Vida?”

“She seems in a trance.”

“That exactly describes her condition,” said my uncle. “I can revive her—perhaps I had better do that now, so that she, too, may hear all the story, of which now she knows only a part.”

I followed him into the dining room to where my darling lay covered by a spread, looking angelically beautiful. Her bosom rose and fell rhythmically in what was apparently natural slumber, but I knew she was in a still deeper sleep than that induced by nature. Uncle Carl rummaged in the sideboard and brought out a bottle of ammonia.

“This will sometimes arouse the subject of a hypnotic trance,” he said.

“It—she is hypnotized?”

“Yes—the devil’s weapon. But the hypnotist is dead. Sometimes only the one inducing the trance can restore the patient or subject, but I think I shall succeed without him—I must do so.”

He bent over the girl and spoke to her.

“Vida,” he said, “awake.”

He held the bottle of ammonia close to her nostrils, and then quickly handing it to me, clapped his hands loudly. To my joy, I saw the color rise in her pale cheeks, and her breast was convulsed with some untoward effort; suddenly she sat up and looked wildly about her—into my face and into Uncle Carl’s. Then she burst into an uncontrollable fit of weeping.

“Thank God!” breathed my uncle, and I echoed his words. In a moment I had gathered her, spread and all, in my arms, and she wept unrestrainedly on my shoulder.

Presently she ceased, and realizing for the first time the scantiness of her attire, drew away with a little cry.

“Tom—Dr. Carl—what has happened? I don’t remember—”

“All is well,” said my uncle. “He is dead.”

“Dead! Where?”

“In the living room. Wait here, my dear, till Tom and I remove the body, and then we will have a talk. Or better, run upstairs and dress—by that time there will be nothing to disturb you in—the other room.”

I took her to the door of her room and came hastily downstairs to where my uncle had already partly composed the limbs of the dead man and thrown the cloak over the evil face, evil in death as in life. Together we lifted the body and carried it into a disused room where we laid it decently on an old cot bed. Then we came back to the living room.

Vida called that she was ready and I went up and brought her down.

Then, the lights full on, the fire going, we heard from the lips of Uncle Carl the story which to this day is as strange in the telling as it is difficult to believe. But I saw—there can be no doubt!

‘‘Seven years ago,” he began, “I was in active practise in Chicago, but already I had begun to specialize almost exclusively upon diseases of the brain. Unlike some of my more hidebound confreres, I gave a great deal of attention to psychology, psycho-analysis (though the phrase was then unused, if it was known) and metaphysics. I believed firmly that somewhere there was a connection between that impalpable thing we call the soul and the material organism called brain, that somewhere between matter and mind lay the solution of our vexatious problems. Thus I became intimate with the man who lies dead in there—whose name I shall withhold, at present. He was a brilliant scholar, but his metier lay along the lines of suggestive therapeutics to even a greater degree than did mine. Hypnosis was his hobby, and he had developed it to a degree far beyond that of any of our modem operators. And he was, at heart, a devil.

“He was older than I. I knew nothing of his family, of his home life. That he was unmarried, I learned by some chance remark he made—that was all. I did not even know where he lived. But we had long discussions in either my office or his, which he frequented at irregular intervals, sometimes sitting far into the night, arguing, speculating, sometimes quarreling. He claimed that good and evil were relative terms and that moral qualities were merely the inventions of man—having no bearing on the deeper things of life. I maintained that somewhere in that mysterious organism called brain lay the controlling element that had to do with the traits of good and evil. I believed that some day I or someone else would discover the means of reaching this element, and perhaps by a psychiatric operation removing entirely the tendency to do or even think evil. He laughed at this theory. ‘It is all a matter outside the brain,’ he asserted, ‘and I have delved into studies that will give me the ability, I hope, to control the powers of evil as one controls a horse by means of the reins and bit.’

“One night, about seven years ago, when I had already known this man for some little time, I was aroused by a ring at my doorbell. My name was on the door-plate, but I seldom had patients at home or was called on a case out of hours. Being unmarried, alone, I had not even a servant then, so I answered the door myself. On the step stood Vida.”

He paused and looked toward the girl, who nodded slowly, flushing at the remembrance.

“She told me her mother was ill and begged me to come. The house was only a few blocks distant. I accompanied her, and on the way she explained that she was home temporarily from the convent and that her mother had had an ‘accident.’ When I saw the poor woman, I knew that the accident was in reality nothing short of a brutal attack. I restored Mrs. Darling to consciousness, and then I demanded to know the cause of the injury—she had apparently been beaten. Both she and Vida refused at first to tell—and then, at my insistence, admitted that a man had been responsible. This man lies dead in that other room. He was the brother of Mrs. Darling—Vida’s uncle.

“But the shock came when I learned the name of the devil who had thus attacked a defenseless woman simply because she begged him to desist in some practise that was becoming abhorrent to her—he lived with the mother and daughter—it was the name of my erstwhile friend and fellow investigator.

“Mrs. Darling was more seriously injured than I at first suspected, but I performed a very slight operation which saved her life.

“The gratitude of both mother and child was affecting, and we became devoted friends. I can say—now that she is no more—how deeply I learned to love Vida’s mother. She was the image, in a matured way, of her daughter. And she was in every respect a wonderful woman. But I could not conceive of myself as married—I was already wedded to science. Furthermore I was considerably older than she.

“I called the brother to account the next day and told him frankly what I thought of him. He laughed like a fiend. But he heeded my warning and for a long time did not molest his sister again. Vida came to work with me as my secretary after a year or so. She has been like a daughter ever since.

“And then one day, about two years ago, that devil again attacked his sister, and from the effects of this injury she did not recover. However, a charge of murder could not be placed against him. The actual physical hurts did not directly induce death. It was the mental enmity and the horror of the man and his practises which resulted in her gradual fading away. Thus he was in every sense morally to blame. Why did I not denounce him? His sister begged me not to do so, as did Vida. And I acceded to their wishes. Then she—died.”

For an instant my uncle bent his head, and Vida’s eyes were suffused with tears. I reached over and put an arm about her as he resumed.

“I forgot everything then but my grief. I knew that I should have sacrificed all for my love, and now it was too late. Then came the thought of revenge. He should pay!

“No matter by what means I induced him to come to my office again in a friendly way, following the trouble and my accusations which had estranged us. I had learned things about him, meanwhile, from both women—from Vida and, before her death, from Mrs. Darling—things which were too unsavory, too horrible—yes, too transcendently terrible—to accept. He dabbled in forbidden things, and made incursions into a realm of which you can have no cognizance. The women knew only that he performed strange experiments in his laboratory and that they found dumb creatures, a black cockerel and a he-goat, which had been killed in a revolting manner. Once, they found the pentagram, with mystic symbols, sketched in chalk on the floor of his study. Always there was an indefinable, an evil odor, in his rooms. They heard him talking to himself at night—but. it sounded as if he were addressing another. Once there were heavy sounds as of some altercation in which things were overturned. He had cried out, and to their questions answered only that he had knocked over a table and hurt his foot. Sometimes there was a trace of unusual heat in the rooms.

“My meetings with Mrs. Darling had been invariably at my office, where Vida was working. Oddly, her uncle had made no effort to prevent her working with me. Perhaps he was glad to be rid of her that he might carry on his experiments the more safely.

“As I say, I induced him to come to see me at my office on several occasions, and one evening shortly after his victim had passed on, we talked later than usual. I was prepared, for I too had been pursuing my studies assiduously. I drugged the wine he drank, and when he was unconscious, administered an anesthetic. I placed him on my operating table and prepared him for an operation. The brain! That was the seat of the trouble. If I could remove that evil tendency by the knife I might make him a worthy member of society, even a valuable one. Also I would prove my theory. And if I failed—well, he deserved death!

“The operation was a success—in so far that he recovered rapidly under my careful nursing. I had removed a tiny particle of the organic matter that constituted what I believed to be the seat of the emotion of evil. But I had made an error. Instead, I had removed the part which contained whatever small amount of good tendency was resident in his brain. In a word, I had constituted him a human monster a hundred times worse than before. For in the worst of us there is always some slight inclination to good; in him there now remained no redeeming feature. I began to note the effect as he recovered strength following the terrific shock of the operation, slight as it had been in some respects. He knew me, but not as in the past. He had forgotten my significance in the scheme of things, he had forgotten his sister and Vida. He had forgotten everything but that certain faces were familiar—as mine. But he was now a cruel animal. He caught the cat I kept in my office, and had I not stopped him in time would have dismembered it in sheer cruelty. He was a monster!

“I let him go. God forgive me, I let loose this hideous thing upon humanity, believing it would soon destroy itself. For a long time it disappeared and I believed that the monster was dead. Then I received a letter from—him!

“He had recovered his memory—but his evil nature was still supreme. He knew instinctively what had happened because I had often aired my theories to him. And he wished only to wreak vengeance on me. Not, he carefully explained, because he regretted losing the slight remnant of good that had remained in his consciousness but because I had tricked him and employed him as a subject for my experiment! He meant to kill me and—Vida! He bade me beware of his powers, of his hypnotic strength, by which even at a distance he could control his victims. He proved this—as you have recently had cause to know—when he subjected Vida to his will, sending her with that stick to—kill! For the stick contains a wicked blade which only a spring in the handle releases. You had not discovered it. And that blade is steeped in deadly virus. But. he reckoned without Vida’s essential goodness. He could not compel her hypnotically to commit a crime, for it was not in her nature to do so.

“He failed in his attempt. . . . but I am ahead of my story. For months he pursued us with threatening letters. For myself I cared little, but I dreaded what might come to Vida. For latterly, the letters conveyed the suggestion that she would be the one to suffer and that through her he would reach me. But as yet the manifestations, if I may so describe them, were witnessed, or felt, by me only. At night I would awake to feel a hot breath in my face; to detect a fetid odor too horrible to be endured; to become aware of something that mopped and mowed [7] in the shadows of the room. It came, I know, like that thing tonight, from the abyss itself—from the very pits of hell! It was wearing me down even as I told myself it could not be so. At least, it was the quintessence of hate, focused upon us, and against this hideous thing even my science was helpless.

“You know now why I could not explain, Tom. You would have thought me mad! But you saw—you saw for yourself, tonight. That awful shape which shrank and vanished before the words I spoke, a formula learned at the cost of diligent research in the ancient volumes known to but few living men, remembered—thank heaven!—tonight in time to save us all. By certain incantations, creatures from that netherworld may be summoned forth, I verily believe. And by opposing words they may be driven back whence they came. You may say it was all hypnotism—that we saw only as the audiences of Hindoo fakers see their marvelous feats, such as the fabled rope trick—but I know better.

“We came here to escape, a few months ago. It. was the last stand in this unequal fight, literally good against evil. I could not touch him with the law—I waited for him to come that I might kill him and by the words I had learned, drive his evil companion back to the abyss. Then I sent for you—I needed a strong arm, Vida needed more than my frail protection—Vida who knew only that the creature once known as her uncle had become an implacable enemy.

“And, as I had hoped, on the failure of his hypnotic effort to influence Vida to slay me (for I assume he did not know of your presence here, Tom), he determined to come himself—accompanied by the dread thing—to achieve his purpose. The rest you know.”

Years have passed. Vida and I have long been happily married and my uncle is dead. He never again spoke of his theory regarding good and evil and the possibility of a material operation on the brain controlling these qualities. Indeed, he retired from all active practise or even experiment following the downfall of his enemy.

Vida and I try to believe it was all a case of hypnosis developed to the tenth degree. The other thing, in spite of what I saw, we can not accept. Sufficient unto their time the foul practises of those remote sorcerers of which, perchance, the man I saw slain was an unholy revenant. Steeped in blood, made hideous by sacrifices of diabolic cruelty, wrapped in the smoke from laurel, cypress and alder, protected by the magic circle of evocation and with altars crowned with asphodel and vervain [8], they worked their spells mayhap in the dim and shadowy past. Today they have no place, and I, for one, refuse to accept, in this respect, even the evidence of my own senses.

Adam Hull Shirk (1887–1931)

_________________________

1. When the character speaks of being in “straitened circumstances”, he is stating he was in a poor situation, and lacking the basic necessities of life.

2. A grip is a small bag you carry in your hand, usually via a couple of handles.

3. Piquant is a French word that is generally used in relation to food, and indicates a spicy taste. However, in the story, Tom uses “piquant” to describe Vida’s face, indicating it has a provactive or stimulating appearance. [Piquant @ Merriam-Webster]

4. In the context of the story, the word crotchet indicates a eccentric idea. [Crotchet @ Merriam-Webster]

5. Although it is no longer common to use the word essayed in this way, it can replace the words “tried” and “attempted”.

6. In the context of the story, spare describes a lean and healthy appearance.

7. The word mowed can be used in a variety of ways. In the context of the story, it can be replaced with grimaced. [Mowed @ Merriam-Webster]

8. Asphodel and vervain are plant species. Both have have associations with witchcraft.

_________________________