The Abyss by Leonid Andreyev

“The Abyss” is a short story by the Russian author Leonid Andreyev (Леонид Андреев). It was first published in 1902, under its original Russian title “Бездна”, and was later translated to English.

In 1946, “The Abyss” was included in the mixed-author anthology Shocking Tales, where it appeared alongside Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Oval Portrait“, “The Tell-Tale Heart“, and “The Cask of Amontillado“; along with the work of other notable English language authors including Oscar Wilde and H. G. Wells.

“The Abyss” has since been republished a number of times, in anthologies such as Strange Desires (1954), A Chamber of Horrors (1965), and A Shocking Thing (1974). It has also been featured on the Pseudopod horror podcast (#336 / May 31, 2013).

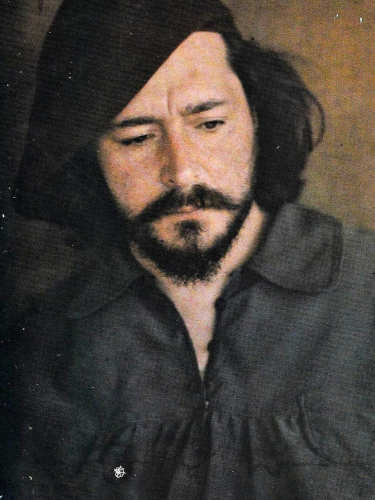

About Leonid Andreyev

Often consdired the Russian equivalent of Edgar Allan Poe, Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev (Леони́д Никола́евич Андре́ев) was a poet, author, and playwright. He was one of the first writers to bring expressionism to Russian Literature.

Born to a middle-class family Andreyev studied law min Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and began working in the legal profession. He also worked as a police-court reporter for a daily newspaper in Moscow.

In his spare time, Andreyev wrote poetry, but made little effort to publish it and most of the poems he offered to editors were rejected. Then, in 1898, the Kur’er, a Moscow newspaper accepted and published his first short story, “Баргамот и Гараська” (“Bargamot and Garaska”). The story impressed the noted Russian writer Maxim Gorky, who advised Andreyev to focus on his literary talents. Andreyev took his advice, eventually gave up his law practice, and quickly became a literary celebrity.

When Andreyev published his first story collection, in 1901, it was an instant success, with sales quickly reaching 250,000 copies. His most famous work is the play He Who Gets Slapped, which preimered at the Moscow Art Theatre on October 27, 1915, and proved to be hugely popular with Russian-speaking audiences, with English versions of the play being successfully staged in theaters all over the world.

The Abyss

By Leonid Andreyev

(Online Text )

The day was coming to an end, but the young pair continued to walk and to talk, observing neither the time nor the way. Before them, in the shadow of a hillock, there loomed the dark mass of a small grove, and between the branches of the trees, like the glowing of coals, the sun blazed, igniting the air and transforming it into a flaming golden dust. So near and so luminous the sun appeared that everything seemed to vanish; it alone remained, and it painted the road with its own fiery tints. It hurt the eyes of the strollers; they turnedback, and all at once everything within their vision was extinguished, became peaceful and clear, and small and intimate. Somewhere afar, barely a mile away, the red sunset seized the tall trunk of a fir, which blazed among the green like a candle in a dark room; the ruddy glow of the road stretched before them, and every stone cast its long black shadow; and the girl’s hair, suffused with the sun’s rays, now shone with a golden-red nimbus. A stray thin hair, wandering the rest, wavered in the air like a golden spider’s thread.

The newly fallen darkness did not break or change the course of their talk. It continued as before, intimately and quietly; it flowed along tranquilly on the same theme: on strength, beauty, and the immortality of love. They were both very young: the girl was no more than seventeen; Nemovetsky was four years older. They wore students’ uniforms: she the modest brown dress of a pupil of a girls’ school, he the handsome attire of a technological student. And, like their conversation, everything about them was young, beautiful,and pure. They had erect, flexible figures, permeated as it were with the clean air and borne along with a light, elastic gait; their fresh voices, sounding even the simplest words with a reflective tenderness, were like a rivulet in a calm spring night, when the snow had not yet wholly thawed from the dark meadows. They walked on, turning the bend of the unfamiliar road, and their lengthening shadows, with absurdly small heads, now advanced separately, now merged into one long, narrow strip, like the shadow of a poplar. But they did not see the shadows, for they were too much absorbed in their talk. While talking, the young man kept his eyes fixed on the girl’s handsome face, upon which the sunset had seemed to leave a measure of its delicate tints. As for her, she lowered her gaze on the footpath, brushed the tiny pebbles to one side with her umbrella, and watched now one foot, now the other as alternately, with a measured step, they emerged from under her dark dress.

The path was intersected by a ditch with edges of dust showing the impress of feet. For an instant they paused. Zinotchka raised her head, looked round her with a perplexed gaze, and asked, “Do you know where we are? I’ve never been here before.”

He made an attentive survey of their position. “Yes, I know. There, behind the hill, is the town. Give me your hand. I’ll help you across.” He stretched out his hand, white and slender like a woman’s, and which did not know hard work.

Zinotchka felt gay. She felt like jumping over the ditch all by herself, running away and shouting, “Catch me!”But she restrained herself, with decorous gratitude inclined her head, and timidly stretched out her hand,which still retained its childish plumpness. He had a desire to squeeze tightly this trembling little hand, but he also restrained himself, and with a half-bow he deferentially took it in his and modestly turned away when in crossing the girl slightly showed her leg.

And once more they walked and talked, but their thoughts were full of the momentary contact of their hands. She still felt the dry heat of his palms and his strong fingers; she felt pleasure and shame, while he was conscious of the submissive softness of her tiny hand and saw the black silhouette of her foot and the small slipper which tenderly embraced it. There was something sharp, something perturbing in this unfading appearance of the narrow hem of white skirts and of the slender foot; with an unconscious effort of will he crushed this feeling. Then he felt more cheerful,and his heart so abundant, so generous in its mood that he wanted to sing, to stretch out his hands to the sky, and to shout: “Run! I want to catch you!”—that ancient formula of primitive love among the woods and thundering waterfalls. And from all these desires tears struggled to the throat.

The long, droll shadows vanished, and the dust of the footpath became gray and cold, but they did not observe this and went on chatting. Both of them had read many good books, and the radiant images of men and women who had loved, suffered, and perished for pure love were borne along before them. Their memories resurrected fragments of nearly forgotten verse,dressed in melodious harmony and the sweet sadness investing love.

“Do you remember where this comes from?” asked Nemovetsky, recalling, “. . . once more she is with me, she whom I love; from whom, having never spoken, I have hidden all my sadness, my tenderness, my love . . .”

“No,” Zinotchka replied, and pensively repeated, “all my sadness, my tenderness, my love . . .”

“All my love,” with an involuntary echo responded Nemovetsky.

Other memories returned to them. They remembered those girls, pure as the white lilies, who, attired in black nunnish garments, sat solitarily in the park,grieving among the dead leaves, yet happy in their grief. They also remembered the men, who, in the abundance of will and pride, yet suffered, and implored the love and the delicate compassion of women. The images thus evoked were sad, but the love which showred in this sadness was radiant and pure. As immense as the world, as bright as the sun, it arose fabulously beautiful before their eyes, and there was nothing mightier or more beautiful on the earth.

“Could you die for love?” Zinotchka asked, as she looked at her childish hand.

“Yes, I could,” Nemovetsky replied, with conviction, and he glanced at her frankly. “And you?”

“Yes, I too.” She grew pensive. “Why, it’s happiness to die for one you love. I should want to.”

Their eyes met. They were such clear, calm eyes, and there was much good in what they conveyed to the other. Their lips smiled. Zinotchka paused.

“Wait a moment,” she said. “You have a thread on your coat.” And trustfully she raised her hand to his shoulder and carefully, with two fingers, removed the thread. “There!” she said and, becoming serious, asked, “Why are you so thin and pale? You are studying too much, I fear. You mustn’t overdo it, you know.”

“You have blue eyes; they have bright points like sparks,” he replied, examining her eyes.

“And yours are black. No, brown. They seem to glow. There is in them . . .” Zinotchka did not finish her sentence, but turned away. Her face slowly flushed, her eyes became timid and confused, while her lips involuntarily smiled. Without waiting for Nemovetsky, who smiled with secret pleasure, she moved forward, but soon paused. “Look, the sun has set!” she exclaimed with grieved astonishment.

“Yes, it has set,” he responded with a new sadness.

The light was gone, the shadows died, everything became pale, dumb, lifeless. At that point of the horizon where earlier the glowing sun had blazed,there now, in silence, crept dark masses of cloud, which step by step consumed the light blue spaces. The clouds gathered, jostled one another, slowly and reticently changed the contours of awakened monsters; they unwillingly advanced, driven, as it were, against their will by some terrible, implacable force. Tearing itself away from the rest, one tiny luminous cloud drifted on alone, a frail fugitive.

Zinotchka’s cheeks grew pale, her lips turned red; the pupils of her eyes imperceptibly broadened, darkening the eyes. She whispered, “I feel frightened. It is so quiet here. Have we lost our way?”

Nemovetsky contracted his heavy eyebrows and made a searching survey of the place. Now that the sun was gone and the approaching night was breathing with fresh air, it seemed cold and uninviting. To all sides the gray field spread, with its scant grass, clay gullies, hillocks and holes. There were many of these holes; some were deep and sheer, others were small and overgrown with slippery grass; the silent dusk of night had already crept into them; and because there was evidence here of men’s labors, the place appeared even more desolate. Here and there,like the coagulations of cold lilac mist, loomed groves and thickets and, as it were, hearkened to what the abandoned holes might have to say to them.

Nemovetsky crushed the heavy, uneasy feeling of perturbation which had arisen in him and said, “No, we have not lost our way. I know the road. First to the left, then through that tiny wood. Are you afraid?”

She bravely smiled and answered, “No. Not now. But we ought to be home soon and have some tea.”

They increased their gait, but soon slowed down again. They did not glance aside, but felt the morose hostility of the dug-up field, which surrounded them with a thousand dim motionless eyes, and this feeling bound them together and evoked memories of childhood. These memories were luminous, full of sunlight,of green foliage, of love and laughter. It was as if that had not been life at all, but an immense, melodious song, and they themselves had been in it as sounds,two slight notes: one clear and resonant like ringingc rystal, the other somewhat more dull yet more animated, like a small bell.

Signs of human life were beginning to appear. Two women were sitting at the edge of a clay hole. One sat with crossed legs and looked fixedly below. She raised her head with its kerchief, revealing tufts of entangled hair. Her bent back threw upward a dirty blouse with its pattern of flowers as big as apples; its strings were undone and hung loosely. She did not look at the passers by. The other woman half reclined nearby, her head thrown backward. She had a coarse, broad face,with a peasant’s features, and, under her eyes, the projecting cheekbones showed two brick-red spots, resembling fresh scratches. She was even filthier than the first woman, and she bluntly stared at the passers by. When they had passed by, she began to sing in a thick, masculine voice:

For you alone, my adored one,

Like a flower I did bloom . . .

“Varka, do you hear?” She turned to her silent companion and, receiving no answer, broke into loud,coarse laughter.

Nemovetsky had known such women, who were filthy even when they were attired in costly handsome dresses; he was used to them, and now they glided away from his glance and vanished, leaving no trace. But Zinotchka, who nearly brushed them with her modest brown dress, felt something hostile, pitiful and evil, which for a moment entered her soul. In a few minutes the impression was obliterated, like the shadow of a cloud running fast across the golden meadow; and when, going in the same direction, there had passed them by a barefoot man, accompanied by the same kind of filthy woman, she saw them but gave them no thought. . . .

And once more they walked on and talked, and behind them there moved, reluctantly, a dark cloud, and cast a transparent shadow. . . .

The darkness imperceptibly and stealthily thickened, so that it bore the impress of day, but day oppressed with illness and quietly dying. Now they talked about those terrible feelings and thoughts which visit man at night, when he cannot sleep, and neither sound nor speech give hindrance; when darkness, immense and multiple-eyed,that is life, closely presses to his very face.

“Can you imagine infinity?” Zinotchka asked him, putting her plump hand to her forehead and tightly closing her eyes.

“No. Infinity . . . No . . .” answered Nemovetsky, also shutting his eyes.

“I sometimes see it. I perceived it for the first time when I was yet quite little. Imagine a great many carts. There stands one cart, then another, a third, carts without end, an infinity of carts. … It is terrible” Zinotchka trembled.

“But why carts?” Nemovetsky smiled, though he felt uncomfortable.

“I don’t know. But I did see carts. One, another . . . without end.”

The darkness stealthily thickened. The cloud had already passed over their heads and, being before them, was now able to look into their lowered, paling faces. The dark figures of ragged, sluttish women appeared oftener; it was as if the deep ground holes, dug for some unknown purpose, cast them up to the surface. Now solitary, now in twos or threes, they appeared,and their voices sounded loud and strangely desolate in the stilled air.

“Who are these women? Where do they all come from?” Zinotchka asked in a low, timorous voice.

Nemovetsky knew who these women were. He felt terrified at having fallen into this evil and dangerous neighborhood, but he answered calmly, “I don’t know. It’s nothing. Let’s not talk about them. It won’t be long now. We only have to pass through this little wood, and we shall reach the gate and town. It’s a pity thatwe started out so late.”

She thought his words absurd. How could he call it late when they started out at four o’clock? She looked at him and smiled. But his eyebrows did not relax, and, in order to calm and comfort him, she suggested, “Let’s walk faster. I want tea. And the wood’s quite near now.”

“Yes, let’s walk faster.”

When they entered the wood and the silent trees joined in an arch above their heads, it became very dark but also very snug and quieting.

“Give me your hand,” proposed Nemovetsky.

Irresolutely she gave him her hand, and the light contact seemed to lighten the darkness. Their hands were motionless and did not press each other. Zinotchka even slightly moved away from her companion. But their whole consciousness was concentrated in the perception of the tiny place of the body where the hands touched one another. And again the desire came to talk about the beauty and the mysterious power of love, but to talk without violating the silence, to talk by means not of words but of glances. And they thought that they ought to glance, and they wanted to, yet they didn’t dare.

“And here are some more people!” said Zinotchka cheerfully.

In the glade, where there was more light, there sat near an empty bottle three men in silence, and expectantly looked at the newcomers. One of them, shaven like an actor, laughed and whistled in such away as if to say, “Oho!”

Nemovetsky’s heart fell and froze in a trepidation of horror, but, as if pushed on from behind, he walked straight on the sitting trio, beside whom ran the footpath. These were waiting, and three pairs of eyes looked at the strollers, motionless and terrifying. And,desirous of gaining the good will of these morose,ragged men, in whose silence he scented a threat, and of winning their sympathy for his helplessness, he asked, “Is this the way to the gate?”

They did not reply. The shaven one whistled something mocking and not quite definable, while the others remained silent and looked at them with a heavy, malignant intentness. They were drunken, and evil, and they were hungry for women and sensual diversion. One of the men, with a ruddy face, rose to his feet like a bear, and sighed heavily. His companions quickly glanced at him, then once more fixed an intent gaze on Zinotchka. “I feel terribly afraid,” she whispered with lips alone.

He did not hear her words, but Nemovetsky understood her from the weight of the arm which leaned on him. And, trying to preserve a demeanor of calm, yet feeling the fated irrevocableness of what was about to happen, he advanced on his way with a measured firmness. Three pairs of eyes approached nearer, gleamed, and were left behind one’s back. “It’s better to run,” thought Nemovetsky and answered himself, “No, it’s better not to run.”

“He’s a dead ‘un! You ain’t afraid of him?” said the third of the sitting trio, a bald-headed fellow with a scant red beard. “And the little girl is a fine one. May God grant everyone such a one!” The trio gave a forced laugh.

“Mister, wait I want to have a word with you!” said the tall man in a thick bass voice and glanced at his comrades. They rose. Nemovetsky walked on, without turning round.

“You ought to stop when you’re asked,” said the red-haired man. “An’ if you don’t, you’re likely to get something you ain’t counting on.”

“D’ you hear?” growled the tall man, and in two jumps caught up with the strollers.

A massive hand descended on Nemovetsky’s shoulder and made him reel. He turned and met very close to his face the round, bulgy, terrible eyes of his assailant. They were so near that it was as if he were looking at them through a magnifying glass, and he clearly distinguished the small red veins on the whites and the yellowish matter on the lids. He let fall Zinotchka’s numb hand and, thrusting his hand into his pocket, he murmured, “Do you want money? I’ll give you some,with pleasure.”

The bulgy eyes grew rounder and gleamed. And when Nemovetsky averted his gaze from them, the tall man stepped slightly back and, with a short blow, struck Nemovetsky’s chin from below.

Nemovetsky’s head fell backward, his teeth clicked, his cap descended to his forehead and fell off; waving with his arms, he dropped to the ground. Silently, without a cry, Zinotchka turned and ran with all the speed of which she was capable. The man with the clean-shaven face gave a long-drawn shout which sounded strangely, “A-aah! . . .” And, still shouting, he gave pursuit.

Nemovetsky, reeling, jumped up, and before he could straighten himself he was again felled with a blow on the neck. There were two of them, and he one, and he was frail and unused to physical combat. Nevertheless, he fought for a long time, scratched with his fingernails like an obstreperous woman, bit with his teeth, and sobbed with an unconscious despair. When he was too weak to do more they lifted him and bore him away. He still resisted, but there was a din in his head; he ceased to understand what was being done with him and hung helplessly in the hands which bore him. The last thing he saw was a fragment of the redbeard which almost touched his mouth, and beyond it the darkness of the wood and the light-colored blouse of the running girl. She ran silently and fast, as she had run but a few days before when they were playing tag; and behind her, with short strides, overtaking her, ran the clean-shaven one. Then Nemovetsky felt an emptiness around him, his heart stopped short as he experienced the sensation of falling, then he struck the earth and lost all consciousness.

The tall man and the red-haired man, having thrown Nemovetsky into a ditch, stopped for a few moments to listen to what was happening at the bottom of the ditch. But their faces and their eyes were turned to one side, in the direction taken by Zinotchka. From there arose the high stifled woman’s cry which quickly died. The tall man muttered angrily, “The pig!”

Then, making a straight line, breaking twigs on the way, like a bear, he began to run. “And me! And me!” his red-haired comrade cried in a thin voice, running after him. He was weak and he panted; in the struggle his knee was hurt, and he felt badly because the idea about the girl had come to him first and he would get her last. He paused to rub his knee; then, putting a finger to his nose, he sneezed; and once more began to run and to cry his plaint, “And me! And me!”

The dark cloud dissipated itself across the whole heavens, ushering in the calm, dark night. The darkness soon swallowed up the short figure of the red haired man, but for some time there was audible the uneven fall of his feet, the rustle of the disturbed leaves, and the shrill, plaintive cry, “And me! Brothers,and me!”

Earth got into Nemovetsky’s mouth, and his teeth grated. On coming to himself, the first feeling he experienced was consciousness of the pungent, pleasant smell of the soil. His head felt dull, as if heavy lead had been poured into it; it was hard to turn it. His whole body ached, there was an intense pain in the shoulder, but no bones were broken. Nemovetsky sat up, and for a long time looked above him, neither thinking nor remembering. Directly over him, a bush lowered its broad leaves, and between them was visible the now clear sky. The cloud had passed over, without dropping a single drop of rain, and leaving the air dry and exhilarating. High up, in the middle of the heavens, appeared the carven moon, with a transparent border. It was living its last nights, and its light was cold, dejected, and solitary. Small tufts of cloud rapidly passed over in the heights where, it was clear, the wind was strong; they did not obscure the moon, but cautiously passed it by.

In the solitariness of the moon,in the timorousness of the high bright clouds, in theblowing of the wind barely perceptible below, one felt the mysterious depth of night dominating over the earth.

Nemovetsky suddenly remembered everything that had happened, and he could not believe that it had happened. All that was so terrible and did not resemble truth. Could truth be so horrible? He, too, as he sat there in the night and looked up at the moon and the running clouds, appeared strange to himself and did not resemble reality. And he began to think that it was an ordinary if horrible nightmare. Those women, of whom they had met so many, had also become a part of this terrible and evil dream.

“It can’t be!” he said with conviction, and weakly shook his heavy head. “It can’t be!”

He stretched out his hand and began to look for his cap. His failure to find it made everything clear to him; and he understood that what had happened had not been a dream, but the horrible truth.

Terror possessed him anew, as a few moments later he made violent exertions to scramble out of the ditch, again and again to fall back with handfuls of soil, only to clutch once more at the hanging shrubbery.

He scrambled out at last, and began to run, thoughtlessly, without choosing a direction. For a long time he went on running, circling among the trees. With equal suddenness, thoughtlessly, he ran in another direction. The branches of the trees scratched his face, and again everything began to resemble a dream. And it seemed to Nemovetsky that something like this had happened to him before: darkness, invisible branches of trees, while he had run with closed eyes, thinking that all this was a dream. Nemovetsky paused, then sat downin an uncomfortable posture on the ground, without any elevation. And again he thought of his cap, and he said, “This is I. I ought to kill myself. Yes, I ought to kill myself, even if this is a dream”

He sprang to his feet, but remembered something and walked slowly, his confused brain trying to picture the place where they had been attacked. It was quite dark in the woods, but sometimes a stray ray of moonlight broke through and deceived him; it lighted up the white tree trunks, and the wood seemed as if it were full of motionless and mysteriously silent people. All this, too, seemed as if it had been, and it resembled a dream.

“Zinaida Nikolaevna!” called Nemovetsky, pronouncing the first word loudly, the second in a lower voice, as if with the loss of his voice he had also lost hope of any response.

And no one responded.

Then he found the footpath, and knew it at once. He reached the glade. Back where he had been, he fully understood that it all had actually happened. He ran about in his terror, and he cried, “Zinaida Nikolaevnal It is I!”

No one answered his call. He turned in the direction where he thought the town lay, and shouted a prolonged shout, “He-l-l-p!”

And once more he ran about, whispering something while he swept the bushes, when before his eyes there appeared a dim white spot, which resembled a spot of congealed faint light. It was the prostrate body ofZinotchka.

“Oh, God! What’s this?” said Nemovetsky, with dry eyes, but in a voice that sobbed. He got down on his knees and came in contact with the girl lying there.

His hand fell on the bared body, which was so smooth and firm and cold but by no means dead. Trembling, he passed his hand over her.

“Darling, sweetheart, it is I,” he whispered, seeking her face in the darkness.

Then he stretched out a hand in another direction,and again came in contact with the naked body, and no matter where he put his hand it touched this woman’s body, which was so smooth and firm and seemed to grow warm under the contact of his hand. Sometimes he snatched his hand away quickly, and again he let it rest; and just as, all tattered and without his cap, he did not appear real to himself, so it was with this bared body: he could not associate it with Zinotchka. All that had passed here, all that men had done with this mute woman’s body, appeared to him in ail its loathsome reality, and found a strange intensely eloquent response in his whole body. He stretched forward in a way that made his joints crackle, dully fixed his eyes on the white spot, and contracted his brows like a man thinking. Horror before what had happened congealed in him, and like a solid lay on his soul, as it were, something extraneous and impotent.

“Oh, God! What’s this?” he repeated, but the sound of it rang untrue, like something deliberate. He felt her heart: it beat faintly but evenly, and when he bent toward her face he became aware of its

equally faint breathing. It was as if Zinotchka were not in a deep swoon, but simply sleeping. He quietly called to her, “Zinotchka, it is I!”

But at once he felt that he would not like to see her awaken for a long time. He held his breath, quickly glanced round him, then he cautiously smoothed her cheek; first he kissed her closed eyes, then her lips, whose softness yielded under his strong kiss. Frightened lest she awaken, he drew back, and remained in a frozen attitude. But the body was motionless and mute, and in its helplessness and easy access there was something pitiful and exasperating, not to be resisted and attracting one to itself. With infinite tenderness and stealthy, timid caution, Nemovetsky tried to cover her with the fragments of her dress, and this double consciousness of the material and the naked body was as sharp as a knife and as incomprehensible as madness. Here had been a banquet of wild beasts . . . he scented the burning passion diffused in the air, and dilated his nostrils.

“It is I! I!” he madly repeated, not understanding what surrounded him and still possessed of the memory of the white hem of the skirt, of the black silhouette of the foot and of the slipper which so tenderly embraced it. As he listened to Zinotchka’s breathing, his eyes fixed on the spot where her face was, he moved a hand. He listened, and moved the hand again.

“What am I doing?” he cried out loudly, in despair,and sprang back, terrified of himself.

For a single instant Zinotchka’s face flashed before him and vanished. He tried to understand that this body was Zinotchka, with whom he had lately walked, and who had spoken of infinity; and he could not understand. He tried to feel the horror of what had happened, but the horror was too great for comprehension, and it did not appear.

“Zinaida Nikolaevna!” he shouted imploringly. “What does this mean? Zinaida Nikolaevna!”

But the tormented body remained mute, and, continuing his mad monologue, Nemovetsky descended on his knees. He implored, threatened, said that he would kill himself, and he grasped the prostrate body, pressing it to him. . . .

The now warmed body softly yielded to his exertions, obediently following his motions, and all this was so terrible, incomprehensible and savage that Nemovetsky once more jumped to his feet and abruptly shouted, “Help!”

But the sound was false, as if it were deliberate. And once more he threw himself on the unresisting

body, with kisses and tears, feeling the presence of some sort of abyss, a dark, terrible, drawing abyss.

There was no Nemovetsky; Nemovetsky had remained somewhere behind, and he who had replaced him was now with passionate sternness mauling the hot, submissive body and was saying with the sly smile of a madman, “Answer me! Or don’t you want to? I love you! I love you!”

With the same sly smile he brought his dilated eyes to Zinotchka’s very face and whispered, “I love you! You don’t want to speak, but you are smiling, I can see that. I love you! I love you! I love you!” He more strongly pressed to him the soft, will-less body, whose lifeless submission awakened a savage passion. He wrung his hands, and hoarsely whispered,”I love you! We will tell no one, and no one will know. I will marry you tomorrow, when you like. I love you. I will kiss you, and you will answer me—yes? Zinotchka . . .” With some force he pressed his lips to hers, and felt

conscious of his teeth’s sharpness in her flesh; in the force and anguish of the kiss he lost the last sparks of reason. It seemed to him that the lips of the girl quivered. For a single instant flaming horror lighted up his mind, opening before him a black abyss.

And the black abyss swallowed him.

Leonid Andreyev (1871 – 1919)