The Devil’s Carbuncle by Lafcadio Hearn

“The Devil’s Carbuncle” was first published 2 November 1879, in The New Orleans Item. In 1879, the story was included in the Lafcadio Hearn short story collection Fantastics and Other Fancies. Rarely reprinted, “The Devil’s Carbuncle” is not a story most people are likely to be familiar with.

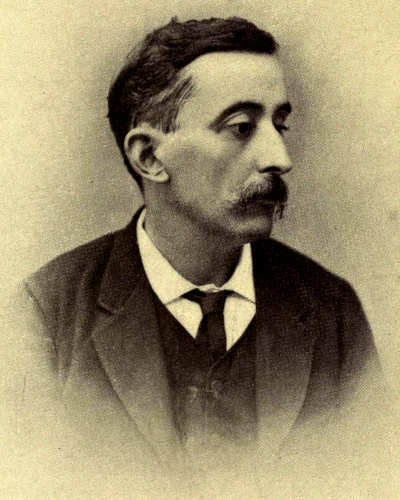

About Lafcadio Hearn

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was a writer, teacher, and translator, who had a very productive life and was a prolific author of speculative fiction. He was Born 27 June 1850, on the Ionian Island of Lefkada, but spent most of his early life in Dublin, Ireland.

When he was 19 years old, Hearn emigrated to the USA and began working as a newspaper reporter. Following a stint working for a newspaper in New Orleans, he became a correspondent to the French West Indies, remaining on the island of Martinique for two years, before relocating to Japan, where he spent the rest of his life. In 1891, he married Setsuko Koizumi, a lady from a high-ranking Samurai family. The couple had four children.

Hearn’s writings about Japan were fundamental in providing the Western world with an insight into what was then an unfamiliar culture. In 1894, many of his articles and essays were collected and published as the two-volume book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

Hearn was at his most prolific between 1896 and 1903, while working as professor of English literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo. He wrote four books during this time, including a collection of supernatural stories called Ghostly Japan (1899).

In addition to producing his own work, Hearn also a translated many of Guy de Maupassant’s stories from French to English.

Lafcadio Hearn died in Tokyo, on 26 September 1904.

The Devil’s Carbuncle

by Lafcadio Hearn

(Online Text)

When Juan de la Torre, one of the celebrated Conquistadores, discovered and seized an immense treasure in one of the huacas near the city of Lima, the Spanish soldiers became seized with a veritable mania for treasure-seeking among the old forts and cemeteries of the Indians. Now there were three ballesteros[1] belonging to the company of Captain Diego Gumiel, who had formed a partnership for the purpose of seeking fortunes among the huacas of Miraflores, and who had already spent weeks upon weeks in digging for treasure without finding the smallest article of value.

On Good Friday, in the year 1547, without any respect for the sanctity of the day,—for to human covetousness nothing is sacred,— the three ballesteros, after vainly sweating and panting all morning and afternoon, had not found anything except a mummy—not even a trinket or bit of pottery worth three pesetas. Thereupon they gave themselves over to the Father of Evil—cursing all the Powers of Heaven, and blaspheming so horribly that the Devil himself was obliged to stop his ears with cotton.

By this time the sun had set; and the adventurers were preparing to return to Lima, cursing the niggardly Indians for the unpardonable stupidity of not having been entombed in state upon beds of solid gold or silver, when one of the Spaniards gave the mummy so ferocious a kick that it rolled a considerable distance. A glimmering jewel dropped from the skeleton, and’ rolled slowly after the mummy.

“Canario!” cried one of the soldiers, “what kind of a taper[2] is that? Santa Maria! what a glorious carbuncle!”

And he was about to walk toward the jewel, when the one who had kicked the corpse, and who was a great bully, held him back with the words:—

“Halt, comrade! May I never be sad if that carbuncle does not belong to me; for it was I who found the mummy!

“May the Devil carry thee away! I first saw it shine, and may I die before any other shall possess it!”

“Cepos quedos!”[3] thundered the third, unsheathing his sword, and making it whistle round his head. “So I am nobody?”

“Caracolines![4] not even the Devil’s wife shall wring it from me,” cried the bully, unsheathing his dagger.

And a tremendous fight began among the three comrades.

The following day some Mitayos found the dead body of one of the combatants, and the other two riddled with wounds, begging for a confessor. Before they died they related the story of the carbuncle, and told how it illumined the combat with a sinister and lurid light. But the carbuncle was never found after. Tradition ascribes its origin to the Devil; and it is said that each Good Friday night travelers may perceive its baleful rays twinkling from the huaca Juliana, rendered famous by this legend.

Lafcadio Hearn (1850 — 1904)

______________________________

1. Ballestro indicates a Spanish soldier armed with a crossbow.

2. The word taper may be the result of a typo, or a problem with the original scan of the text. Every copy of the story I have been able to access contains the word taper, but, due to the context, it seems inappropriate. However, a taper is a type of candle. Although the text does not state the characters were using candles, it may be the character is so taken aback by the glimmer of the jewel that he is questioning if the glimmer is due to an unusually powerful candle. Alternatively, the word may be caper. Given the context, this seems more likely.

3. In Spanish, cepos cuedos can be used as a command or request to “stand still” or “be still”, however, given the way it’s used in the story, a more appropriate translation may be “halt”.

4. Caracolines means little snails. It may be the character is using it as a exclamation, or, as we are told he is a bully, is actually calling his comrades “little snails”.

______________________________