Varney the Vampire Errors and Inconsistencies

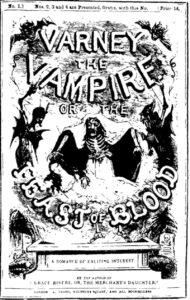

Varney the Vampire (full title: Varney the Vampire, or the Feast of Blood) is one of the most important works of vampire fiction, and is notable as being the vampire story that introduces the concept of vampires with sharp, fang-like teeth. First published as a series of penny dreadfuls, between 1845 and 1847, Varney the Vampire is believed to have influenced Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu when he wrote his novella Carmilla (1872), and both Varney the Vampire and Camilla appear to have influenced Bram Stoker when he wrote Dracula (1897).

However, although the importance of this penny dreadful horror story cannot be denied, nor can the many errors and inconsistencies. in the text Among other things, some paragraphs contain mixed tenses that can cause reader confusion, and instead of being neat and concise, the text tends to ramble on. This fluffing out of the story may be explained by the fact its author(s) were paid by the line; so spinning things out would have served to put extra money in their pockets.

As I progress through the story, I will add any obvious errors (some of which can be very confusing) to this page. No doubt, there will be things that I fail to notice, or do not realize due to lack of knowledge in certain areas, such as history. Nevertheless, it is my hope that this page may be useful to people who are working their way through the Varney the Vampire online book available on this, print versions, or versions available via other websites.

Error in the Preface to the Original Book

In 1887, after the penny dreadful series had run its course, Varney the Vampire was printed as a book. In the preface, it’s author, begins by pointing out the story’s unprecedented success, then goes on to state:

“A belief in the existence of Vampyres first took its rise in Norway and Sweden from whence it rapidly spread to more southern regions, taking a firm hold of the imaginations of the more credulous portion of mankind.”

This is likely the first error in Varney the Vampire the book. The belief in such creatures is integral to many cultures around the world. Ancient civilizations such as the Mesopotamians, Hebrews, ancient Greeks, and Romans had tales of demonic blood-drinking entities. [Further Reading]

This error is made more unforgivable by the fact that Chapter XL contains contrary information:

“That dim and uncertain condition concerning vampyres, originating probably as it had done in #Germany, had spread itself slowly, but insidiously, throughout the whole of the civilized world.”

Inconsistencies Relating to Varney’s Age

In the third chapter, Henry tells Mr. Marchdale his ancestor died about 90 years ago. Then, in the fifth chapter, he states his ancestor committed suicide 100 years ago.

Sir Francis Varney’s Offer of Assistance

The fifth chapter begins with Henry Bannerworth receiving a letter from Sir Francis Varney (Varney the Vampire). However, Henry shot the vampire at the end of the second chapter, and he is not seen again until later on in chapter 5, when his dead body is reanimated by moonlight. Prior to this, Varney would have been out of commission and unable to write such a letter.

Discrepancies Over the Vampire’s Name

In chapter III, Henry and Mr. Marchdale agree the man in the portrait on the wall of Flora’s chamber looks like the fiend who attacked her [Varney the Vampire]. Henry then tells Mr. Marchdale, the man in portrait is Sir Runnagate Bannerworth:

“It is,” said Henry, “the portrait of Sir Runnagate Bannerworth, an ancestor of ours, who first, by his vices, gave the great blow to the family prosperity.”

However, in Chapter VIII; while Henry, George, Mr. Marchdale, and Mr. Chiilingworth are searcing the family tomb in an attempt to discover the resting place of the “ancestor”; George identifies him as Marmaduke Bannerworth:

“We shall arrive at no conclusion,” said George. “All seems to have rotted away among those coffins where we might expect to find the one belonging to Marmaduke Bannerworth, our ancestor.“

Errors in Dialogue Attribution

Chapter XII

In chapter XII, the writer appears to lose the plot midway through the chapter and forget which character is speaking, causing the story to become a little hard to follow.

The problem occurs during a dialogue between Charles Holland and Henry Bannerworth:

Paragraph 80: “I had a strange presentiment, now,” added Charles, “that we should make some discovery that would repay us for our trouble. It appears, however, that such is not to be the case; for you see nothing presents itself to us but the most ordinary appearances.” [This is obviously Charles speaking]

Paragraph 81:”I perceive as much; and the panel itself, although of more than ordinary thickness, is, after all, but a bit of planed oak, and apparently fashioned for no other object than to paint the portrait on.” [This appears to be Henry Speaking]

Paragraph 82:”True. Shall we replace it?” [This should be Charles speaking, but the next paragraph suggests otherwise]

Paragraph 83: Charles reluctantly assented, and the picture was replaced in its original position. We say Charles reluctantly assented, because, although he had now had ocular demonstration that there was really nothing behind the panel but the ordinary woodwork which might have been expected from the construction of the old house, yet he could not, even with such a fact staring him in the face, get rid entirely of the feeling that had come across him, to the effect that the picture had some mystery or another.

On closer inspection, the problem appears to be caused by sloppy editing. After the paragraph 80, where Charles states he had a strange presentment, the writer appears to have rewritten Henry’s Response. We know this because, due to the context, in paragraphs 81 and 82, it can only be Henry who is speaking. Bearing in mind the fact the author(s) of Varney the Vampire were paid by the line, it seems likely that Henry’s original reply was short and sweet: “True. Shall we replace it?”, and the writer then fluffed out the response because extra lines meant extra money. If this is so, he must have forgotten to remove the original response—and the editors obviously never noticed the mistake—meaning his attempt to push up his earnings was doubly successful.

A similar error occurs later, in paragraph 113 of the same chapter. After Charles and Henry had become “silent” and “lost in wonder” in paragraph 111, one of them breaks the silences, and says, “Human means against such an appearance as we saw to-night are evidently useless.” The author wrongly attributes the comment to Charles. However, on hearing the words, Mr. Marchdale takes Henry by the arm and attempts to reassure him, indicating it was Henry who was speaking, not Charles.

Chapter XVII

In Chapter XVII, during a conversation with Henry Bannerworth, Charles Holland, who has noticed Sir Francis Varney has a wounded arm, states: “There, then, was where the bullet from the pistol fired by Flora, when we were at the church, hit him.” However, it is not a case of “we” were at the church. Henry, George, Mr, Marchdale, and Mr. Chillingworth visted the vault under the church. At that point, although Charles had been referred to in Chapter VI, he was yet to take an active role in the story. He first appears in Chapter X, when Henry and the others return from the church, and find Flora, who has just discharged her pistol, is in the young man’s arms.

Losing track of Important Elements of the Story

In Chapter XXXII, Missnames Bannerworth Hall, calling it Bannerworth House.