El Vómito by Lafcadio Hearn

“El Vomito” was first published on 21 March 1881, in The New Orleans Item. In 1914, 10 years after the author’s death, it was reprinted in the anthology Fantasies and Other Fancies.

El vomito is Spanish word for “the vomit”. However, in this case, a literal translation does not apply. In the Carribean and Gulf region, “el vomito” was a colloquial term for yellow fever. It was short for “el vomito negro”—the black vomit.[1] Black vomit is one of the symptoms of the disease.

Hearn’s “El Vomito” is not a long story, and can be read quite quickly, but the tale is more complex than it initially appears. Although the mother and daughter insist the sick man is suffering from el vomito, working on another level, this appears to be a form of vampire story—and very cleverly done. Just as the sick man succumbs to his “sickness”, the doctor who attends him succumbs to the mother and daughter’s corruption. It’s a powerful story told in fewer than 1,100 words.

About Lafcadio Hearn

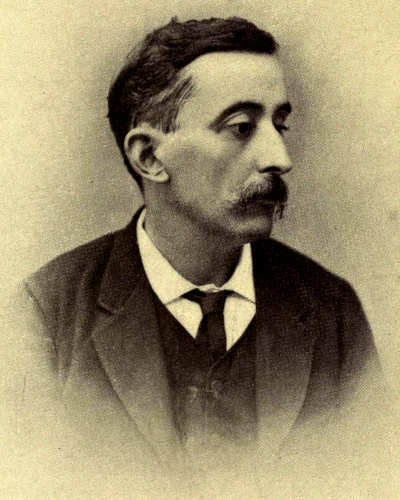

Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was a writer, teacher, and translator, who had a very productive life and was a prolific author of speculative fiction. He was Born 27 June 1850, on the Ionian Island of Lefkada, but spent most of his early life in Dublin, Ireland.

When he was 19 years old, Hearn emigrated to the USA and began working as a newspaper reporter. Following a stint working for a newspaper in New Orleans, he became a correspondent to the French West Indies, remaining on the island of Martinique for two years, before relocating to Japan, where he spent the rest of his life. In 1891, he married Setsuko Koizumi, a lady from a high-ranking Samurai family. The couple had four children.

Hearn’s writings about Japan were fundamental in providing the Western world with an insight into what was then an unfamiliar culture. In 1894, many of his articles and essays were collected and published as the two-volume book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan.

Hearn was at his most prolific between 1896 and 1903, while working as professor of English literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo. He wrote four books during this time, including a collection of supernatural stories called Ghostly Japan (1899).

In addition to producing his own work, Hearn also a translated many of Guy de Maupassant’s stories from French to English.

Lafcadio Hearn died in Tokyo, on 26 September 1904.

El Vómito

by Lafcadio Hearn

(Online Text)

The mother was a small and almost grotesque personage, with a somewhat medieval face, oaken colored and long and full of Gothic angularity; only her eyes were young, full of vivacity and keen comprehension. The daughter was tall and slight and dark; a skin with the tint of Mexican gold; hair dead black and heavy with snaky ripples in it that made one think of Medusa; eyes large and of almost sinister brilliancy, heavily shadowed and steady as a falcon’s; she had that lengthened grace of dancing figures on Greek vases, but on her face reigned the motionless beauty of bronze—never a smile or frown. The mother, a professed sorceress, who told the fortunes of veiled women by the light of a lamp burning before a skull, did not seem to me half so weird a creature as the daughter. The girl always made me think of Southey’s witch, kept young by enchantment to charm Thalaba.[2]

* * *

The house was a mysterious ruin: walls green with morbid vegetation of some fungous kind; humid rooms with rotting furniture of a luxurious and antiquated pattern; shrieking stairways; yielding and groaning floors; corridors forever dripping with a cold sweat; bats under the roof and rats under the floor; snails moving up and down by night in wakes of phosphorescent slime; broken shutters, shattered glass, lockless doors, mysterious icy draughts, and elfish noises. Outside there was a kind of savage garden,—torchon trees, vines bearing spotted and suspicious flowers, Spanish bayonets growing in broken urns, agaves, palmettoes, something that looked like green elephant’s ears, a monstrous and ill-smelling species of lily with a phallic pistil, and many vegetable eccentricities I have never seen before. In a little stable-yard at the farther end were dyspeptic chickens, nostalgic ducks, and a most ancient and rheumatic horse, whose feet were always in water, and who made nightmare moanings through all the hours of darkness. There were also dogs that never barked and spectral cats that never had a kittenhood. Still the very ghastliness of the place had its fantastic charm for me. I remained; the drowsy Southern spring came to vitalize vines and lend a Japanese monstrosity to the tropical jungle under my balconied window. Unfamiliar and extraordinary odors floated up from the spotted flowers; and the snails crawled upstairs less frequently than before. Then a fierce and fevered summer!

* * *

It was late in the night when I was summoned to the Cuban’s bedside:—a night of such stifling and motionless heat as precedes a Gulf storm: the moon, magnified by the vapors, wore a spectral nimbus; the horizon pulsed with feverish lightnings. Its white flicker made shadowy the lamp-flame in the sick-room at intervals. I bade them close the windows. “El Vómito?”—already delirious; strange ravings; the fine dark face phantom-shadowed by death; singular[3] and unfamiliar symptoms of pulsation and temperature; extraordinary mental disturbance. Could this be Vómito? There was an odd odor in the room—ghostly, faint, but sufficiently perceptible to affect the memory:—I suddenly remembered the balcony overhanging the African wildness of the garden, the strange vines that clung with webbed feet to the ruined wall, and the peculiar, heavy, sickly, somnolent smell of the spotted blossoms!—And as I leaned over the patient, I became aware of another perfume in the room, a perfume that impregnated the pillow,—the odor of a woman’s hair, the incense of a woman’s youth mingling with the phantoms of the flowers, as ambrosia with venom, life with death, a breath from paradise with an exhalation from hell. From the bloodless lips of the sufferer, as from the mouth of one oppressed by some hideous dream, escaped the name of the witch’s daughter. And suddenly the house shuddered through all its framework, as if under the weight of invisible blows:—a mighty shaking of walls and windows—the storm knocking at the door.

* * *

I found myself alone with her; the moans of the dying could not be shut out; and the storm knocked louder and more loudly, demanding entrance. “It is not the fever,” I said. “I have lived in lands of tropical fever; your lips are even now humid with his kisses, and you have condemned him. My knowledge avails nothing against this infernal craft; but I know also that you must know the antidote which will baffle death;—this man shall not die!—I do not fear you!—I will denounce you!—He shall not die!”

For the first time I beheld her smile—the smile of secret strength that scorns opposition. Gleaming through the diaphanous whiteness of her loose robe, the lamplight wrought in silhouette the serpentine grace of her body like the figure of an Egyptian dancer in a mist of veils, and her splendid hair coiled about her like the viperine locks of a gorgon.

“La voluntad de mi madret”[4] she answered calmly. “You are too late! You shall not denounce us! Even could you do so, you could prove nothing. Your science, as you have said, is worth nothing here. Do you pity the fly that nourishes the spider? You shall do nothing so foolish, señor doctor, but you will certify that the stranger has died of the vómito. You do not know anything; you shall not know anything. You will be recompensed. We are rich.”—Without, the knocking increased, as if the thunder sought to enter: I, within, looked upon her face, and the face was passionless and motionless as the face of a woman of bronze.

* * *

She had not spoken, but I felt her serpent litheness wound about me, her heart beating against my breast, her arms tightening about my neck, the perfume of her hair and of her youth and of her breath intoxicating me as an exhalation of enchantment. I could not speak; I could not resist; spellbound by a mingling of fascination and pleasure, witchcraft and passion, weakness and fear—and the storm awfully knocked without, as if summoning the stranger; and his moaning ceased.

* * *

Whence she came, the mother, I know not. She seemed to have risen from beneath:—

“The doctor is conscientious!—he cares for his patient well. The stranger will need his excellent attention no more. The conscientious doctor has accepted his recompense; he will certify what we desire,—will he not, hija mia?”[5]

And the girl mocked me with her eyes, and laughed fiercely.

Lafcadio Hearn (1850 — 1904)

______________________________

1. The Cambridge World History of Human Disease, VIII. 158 – Yellow Fever

2. “The girl always made me think of Southey’s witch, kept young by enchantment to charm Thalaba.“: The character in the story is referencing Thalaba the Destroyer—an epic poem written by the English poet Robert Southey (1774 – 1843). The poem is so long it is divided into 12 books. In one of them, the hero, Thalabra, encounter a witch who has preserved her youth and beauty through magic. The witch tries to seduce Thalabra to distract him from his mission.

3. The word singular can be used in several ways. In the context of the story, it indicates something that is unusual, odd, or peculiar. [Singular @ Merriam Webster]

4. La voluntad de mi madret: “The will of my mother”, or “My mother’s will”. [Madre is the Spanish word for mother. In this case, there is a letter “t” affixed to the end. This could have been a typo in the original text. It may also reflect a particular regional usage that Hearn was familiar with due to his experiences living in New Orleans (1877 —1887); where, along with French, Spanish was a common language in Creole quarters.

5. “Hija mia” is Spanish for “my daughter”.

______________________________