Public Domain Text: A Happy Release by Sabine Baring-Gould

A Happy Release was first published in Sabine Baring-Gould’s short story collection A Book of Ghosts (1904)

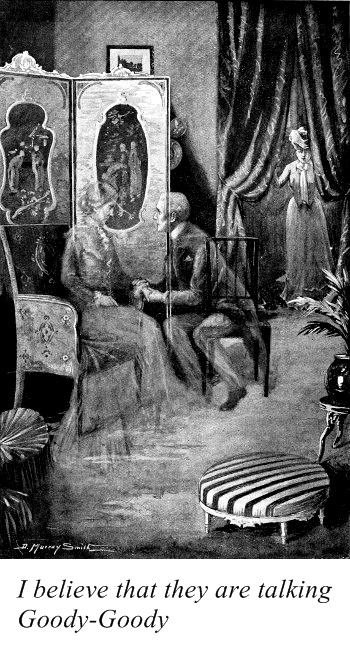

A Book of Ghosts was illustrated by D. Murray Smith . This page includes a copy of his illustration for A Happy Release.

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

A Happy Release by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

Mr. Benjamin Woolfield was a widower. For twelve months he put on mourning. The mourning was external, and by no means represented the condition of his feelings; for his married life had not been happy. He and Kesiah had been unequally yoked together. The Mosaic law forbade the union of the ox and the ass to draw one plough; and two more uncongenial creatures than Benjamin and Kesiah could hardly have been coupled to draw the matrimonial furrow.

She was a Plymouth Sister, and he, as she repeatedly informed him whenever he indulged in light reading, laughed, smoked, went out shooting, or drank a glass of wine, was of the earth, earthy, and a miserable worldling.

For some years Mr. Woolfield had been made to feel as though he were a moral and religious pariah. Kesiah had invited to the house and to meals, those of her own way of thinking, and on such occasions had spared no pains to have the table well served, for the elect are particular about their feeding, if indifferent as to their drinks. On such occasions, moreover, when Benjamin had sat at the bottom of his own table, he had been made to feel that he was a worm to be trodden on. The topics of conversation were such as were far beyond his horizon, and concerned matters of which he was ignorant. He attempted at intervals to enter into the circle of talk. He knew that such themes as football matches, horse races, and cricket were taboo, but he did suppose that home or foreign politics might interest the guests of Kesiah. But he soon learned that this was not the case, unless such matters tended to the fulfilment of prophecy.

When, however, in his turn, Benjamin invited home to dinner some of his old friends, he found that all provided for them was hashed mutton, cottage pie, and tapioca pudding. But even these could have been stomached, had not Mrs. Woolfield sat stern and silent at the head of the table, not uttering a word, but giving vent to occasional, very audible sighs.

When the year of mourning was well over, Mr. Woolfield put on a light suit, and contented himself, as an indication of bereavement, with a slight black band round the left arm. He also began to look about him for someone who might make up for the years during which he had felt like a crushed strawberry.

And in casting his inquiring eye about, it lighted upon Philippa Weston, a bright, vigorous young lady, well educated and intelligent. She was aged twenty-four and he was but eighteen years older, a difference on the right side.

It took Mr. Woolfield but a short courtship to reach an understanding, and he became engaged.

On the same evening upon which he had received a satisfactory answer to the question put to her, and had pressed for an early marriage, to which also consent had been accorded, he sat by his study fire, with his hands on his knees, looking into the embers and building love-castles there. Then he smiled and patted his knees.

He was startled from his honey reveries by a sniff. He looked round. There was a familiar ring in that sniff which was unpleasant to him.

What he then saw dissipated his rosy dreams, and sent his blood to his heart.

At the table sat his Kesiah, looking at him with her beady black eyes, and with stern lines in her face. He was so startled and shocked that he could not speak.

“Benjamin,” said the apparition, “I know your purpose. It shall never be carried to accomplishment. I will prevent it.”

“Prevent what, my love, my treasure?” he gathered up his faculties to reply.

“It is in vain that you assume that infantile look of innocence,” said his deceased wife. “You shall never—never—lead her to the hymeneal altar.”

“Lead whom, my idol? You astound me.”

“I know all. I can read your heart. A lost being though you be, you have still me to watch over you. When you quit this earthly tabernacle, if you have given up taking in the Field, and have come to realise your fallen condition, there is a chance—a distant chance—but yet one of our union becoming eternal.”

“You don’t mean to say so,” said Mr. Woolfield, his jaw falling.

“There is—there is that to look to. That to lead you to turn over a new leaf. But it can never be if you become united to that Flibbertigibbet.”

Mentally, Benjamin said: “I must hurry up with my marriage!” Vocally he said: “Dear me! Dear me!”

“My care for you is still so great,” continued the apparition, “that I intend to haunt you by night and by day, till that engagement be broken off.”

“I would not put you to so much trouble,” said he.

“It is my duty,” replied the late Mrs. Woolfield sternly.

“You are oppressively kind,” sighed the widower.

At dinner that evening Mr. Woolfield had a friend to keep him company, a friend to whom he had poured out his heart. To his dismay, he saw seated opposite him the form of his deceased wife.

He tried to be lively; he cracked jokes, but the sight of the grim face and the stony eyes riveted on him damped his spirits, and all his mirth died away.

“You seem to be out of sorts to-night,” said his friend.

“I am sorry that I act so bad a host,” apologised Mr. Woolfield. “Two is company, three is none.”

“But we are only two here to-night.”

“My wife is with me in spirit.”

“Which, she that was, or she that is to be?”

Mr. Woolfield looked with timid eyes towards her who sat at the end of the table. She was raising her hands in holy horror, and her face was black with frowns.

His friend said to himself when he left: “Oh, these lovers! They are never themselves so long as the fit lasts.”

Mr. Woolfield retired early to bed. When a man has screwed himself up to proposing to a lady, it has taken a great deal out of him, and nature demands rest. It was so with Benjamin; he was sleepy. A nice little fire burned in his grate. He undressed and slipped between the sheets.

Before he put out the light he became aware that the late Mrs. Woolfield was standing by his bedside with a nightcap on her head.

“I am cold,” said she, “bitterly cold.”

“I am sorry to hear it, my dear,” said Benjamin.

“The grave is cold as ice,” she said. “I am going to step into bed.”

“No—never!” exclaimed the widower, sitting up. “It won’t do. It really won’t. You will draw all the vital heat out of me, and I shall be laid up with rheumatic fever. It will be ten times worse than damp sheets.”

“I am coming to bed,” repeated the deceased lady, inflexible as ever in carrying out her will.

As she stepped in Mr. Woolfield crept out on the side of the fire and seated himself by the grate.

He sat there some considerable time, and then, feeling cold, he fetched his dressing-gown and enveloped himself in that.

He looked at the bed. In it lay the deceased lady with her long slit of a mouth shut like a rat-trap, and her hard eyes fixed on him.

“It is of no use your thinking of marrying, Benjamin,” she said. “I shall haunt you till you give it up.”

Mr. Woolfield sat by his fire all night, and only dozed off towards morning.

During the day he called at the house of Miss Weston, and was shown into the drawing-room. But there, standing behind her chair, was his deceased wife with her arms folded on the back of the seat, glowering at him.

It was impossible for the usual tender passages to ensue between the lovers with a witness present, expressing by gesture her disapproval of such matters and her inflexible determination to force on a rupture.

The dear departed did not attend Mr. Woolfield continuously during the day, but appeared at intervals. He could never say when he would be free, when she would not turn up.

In the evening he rang for the housemaid. “Jemima,” he said, “put two hot bottles into my bed to-night. It is somewhat chilly.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And let the water be boiling—not with the chill off.”

“Yes, sir.”

When somewhat late Mr. Woolfield retired to his room he found, as he had feared, that his late wife was there before him. She lay in the bed with her mouth snapped, her eyes like black balls, staring at him.

“My dear,” said Benjamin, “I hope you are more comfortable.”

“I’m cold, deadly cold.”

“But I trust you are enjoying the hot bottles.”

“I lack animal heat,” replied the late Mrs. Woolfield.

Benjamin fled the room and returned to his study, where he unlocked his spirit case and filled his pipe. The fire was burning. He made it up. He would sit there all night During the passing hours, however, he was not left quite alone. At intervals the door was gently opened, and the night-capped head of the late Mrs. Woolfield was thrust in.

“Don’t think, Benjamin, that your engagement will lead to anything,” she would say, “because it will not. I shall stop it.”

So time passed. Mr. Woolfield found it impossible to escape this persecution. He lost spirits; he lost flesh.

At last, after sad thought, he saw but one way of relief, and that was to submit. And in order to break off the engagement he must have a prolonged interview with Philippa. He went to the theatre and bought two stall tickets, and sent one to her with the earnest request that she would accept it and meet him that evening at the theatre. He had something to communicate of the utmost importance.

At the theatre he knew that he would be safe; the principles of Kesiah would not suffer her to enter there.

At the proper time Mr. Woolfield drove round to Miss Weston’s, picked her up, and together they went to the theatre and took their places in the stalls. Their seats were side by side.

“I am so glad you have been able to come,” said Benjamin. “I have a most shocking disclosure to make to you. I am afraid that—but I hardly know how to say it—that—I really must break it off.”

“Break what off?”

“Our engagement.”

“Nonsense. I have been fitted for my trousseau.”

“Your what?”

“My wedding-dresses.”

“Oh, I beg pardon. I did not understand your French pronunciation. I thought—but it does not matter what I thought.”

“Pray what is the sense of this?”

“Philippa, my affection for you is unabated. Do not suppose that I love you one whit the less. But I am oppressed by a horrible nightmare—daymare as well. I am haunted.”

“Haunted, indeed!”

“Yes; by my late wife. She allows me no peace. She has made up her mind that I shall not marry you.”

“Oh! Is that all? I am haunted also.”

“Surely not?”

“It is a fact.”

“Hush, hush!” from persons in front and at the side. Neither Ben nor Philippa had noticed that the curtain had risen and that the play had begun.

“We are disturbing the audience,” whispered Mr. Woolfield. “Let us go out into the passage and promenade there, and then we can talk freely.”

So both rose, left their stalls, and went into the couloir.

“Look here, Philippa,” said he, offering the girl his arm, which she took, “the case is serious. I am badgered out of my reason, out of my health, by the late Mrs. Woolfield. She always had an iron will, and she has intimated to me that she will force me to give you up.”

“Defy her.”

“I cannot.”

“Tut! these ghosts are exacting. Give them an inch and they take an ell. They are like old servants; if you yield to them they tyrannise over you.”

“But how do you know, Philippa, dearest?”

“Because, as I said, I also am haunted.”

“That only makes the matter more hopeless.”

“On the contrary, it only shows how well suited we are to each other. We are in one box.”

“Philippa, it is a dreadful thing. When my wife was dying she told me she was going to a better world, and that we should never meet again. And she has not kept her word.”

The girl laughed. “Rag her with it.”

“How can I?”

“You can do it perfectly. Ask her why she is left out in the cold. Give her a piece of your mind. Make it unpleasant for her. I give Jehu no good time.”

“Who is Jehu?”

“Jehu Post is the ghost who haunts me. When in the flesh he was a great admirer of mine, and in his cumbrous way tried to court me; but I never liked him, and gave him no encouragement. I snubbed him unmercifully, but he was one of those self-satisfied, self-assured creatures incapable of taking a snubbing. He was a Plymouth Brother.”

“My wife was a Plymouth Sister.”

“I know she was, and I always felt for you. It was so sad. Well, to go on with my story. In a frivolous mood Jehu took to a bicycle, and the very first time he scorched he was thrown, and so injured his back that he died in a week. Before he departed he entreated that I would see him; so I could not be nasty, and I went. And he told me then that he was about to be wrapped in glory. I asked him if this were so certain. ‘Cocksure’ was his reply; and they were his last words. And he has not kept his word.”

“And he haunts you now?”

“Yes. He dangles about with his great ox-eyes fixed on me. But as to his envelope of glory I have not seen a fag end of it, and I have told him so.”

“Do you really mean this, Philippa?”

“I do. He wrings his hands and sighs. He gets no change out of me, I promise you.”

“This is a very strange condition of affairs.”

“It only shows how well matched we are. I do not suppose you will find two other people in England so situated as we are, and therefore so admirably suited to one another.”

“There is much in what you say. But how are we to rid ourselves of the nuisance—for it is a nuisance being thus haunted. We cannot spend all our time in a theatre.”

“We must defy them. Marry in spite of them.”

“I never did defy my wife when she was alive. I do not know how to pluck up courage now that she is dead. Feel my hand, Philippa, how it trembles. She has broken my nerve. When I was young I could play spellikins—my hand was so steady. Now I am quite incapable of doing anything with the little sticks.”

“Well, hearken to what I propose,” said Miss Weston. “I will beard the old cat——”

“Hush, not so disrespectful; she was my wife.”

“Well, then, the ghostly old lady, in her den. You think she will appear if I go to pay you a visit?”

“Sure of it. She is consumed with jealousy. She had no personal attractions herself, and you have a thousand. I never knew whether she loved me, but she was always confoundedly jealous of me.”

“Very well, then. You have often spoken to me about changes in the decoration of your villa. Suppose I call on you to-morrow afternoon, and you shall show me what your schemes are.”

“And your ghost, will he attend you?”

“Most probably. He also is as jealous as a ghost can well be.”

“Well, so be it. I shall await your coming with impatience. Now, then, we may as well go to our respective homes.”

A cab was accordingly summoned, and after Mr. Woolfield had handed Philippa in, and she had taken her seat in the back, he entered and planted himself with his back to the driver.

“Why do you not sit by me?” asked the girl.

“I can’t,” replied Benjamin. “Perhaps you may not see, but I do, my deceased wife is in the cab, and occupies the place on your left.”

“Sit on her,” urged Philippa.

“I haven’t the effrontery to do it,” gasped Ben.

“Will you believe me,” whispered the young lady, leaning over to speak to Mr. Woolfield, “I have seen Jehu Post hovering about the theatre door, wringing his white hands and turning up his eyes. I suspect he is running after the cab.”

As soon as Mr. Woolfield had deposited his bride-elect at her residence he ordered the cabman to drive him home. Then he was alone in the conveyance with the ghost. As each gaslight was passed the flash came over the cadaverous face opposite him, and sparks of fire kindled momentarily in the stony eyes.

“Benjamin!” she said, “Benjamin! Oh, Benjamin! Do not suppose that I shall permit it. You may writhe and twist, you may plot and contrive how you will, I will stand between you and her as a wall of ice.”

Next day, in the afternoon, Philippa Weston arrived at the house. The late Mrs. Woolfield had, however, apparently obtained an inkling of what was intended, for she was already there, in the drawing-room, seated in an armchair with her hands raised and clasped, looking stonily before her. She had a white face, no lips that showed, and her dark hair was dressed in two black slabs, one on each side of the temples. It was done in a knot behind. She wore no ornaments of any kind.

In came Miss Weston, a pretty girl, coquettishly dressed in colours, with sparkling eyes and laughing lips. As she had predicted, she was followed by her attendant spectre, a tall, gaunt young man in a black frock-coat, with a melancholy face and large ox-eyes. He shambled in shyly, looking from side to side. He had white hands and long, lean fingers. Every now and then he put his hands behind him, up his back, under the tails of his coat, and rubbed his spine where he had received his mortal injury in cycling. Almost as soon as he entered he noticed the ghost of Mrs. Woolfield that was, and made an awkward bow. Her eyebrows rose, and a faint wintry smile of recognition lighted up her cheeks.

“I believe I have the honour of saluting Sister Kesiah,” said the ghost of Jehu Post, and he assumed a posture of ecstasy.

“It is even so, Brother Jehu.”

“And how do you find yourself, sister—out of the flesh?”

The late Mrs. Woolfield looked disconcerted, hesitated a moment, as if she found some difficulty in answering, and then, after a while, said: “I suppose, much as do you, brother.”

“It is a melancholy duty that detains me here below,” said Jehu Post’s ghost.

“The same may be said of me,” observed the spirit of the deceased Mrs. Woolfield. “Pray take a chair.”

“I am greatly obliged, sister. My back——”

Philippa nudged Benjamin, and unobserved by the ghosts, both slipped into the adjoining room by a doorway over which hung velvet curtains.

In this room, on the table, Mr. Woolfield had collected patterns of chintzes and books of wall-papers.

There the engaged pair remained, discussing what curtains would go with the chintz coverings of the sofa and chairs, and what papers would harmonise with both.

“I see,” said Philippa, “that you have plates hung on the walls. I don’t like them: it is no longer in good form. If they be worth anything you must have a cabinet with glass doors for the china. How about the carpets?”

“There is the drawing-room,” said Benjamin.

“No, we won’t go in there and disturb the ghosts,” said Philippa. “We’ll take the drawing-room for granted.”

“Well—come with me to the dining-room. We can reach it by another door.”

In the room they now entered the carpet was in fairly good condition, except at the head and bottom of the table, where it was worn. This was especially the case at the bottom, where Mr. Woolfield had usually sat. There, when his wife had lectured, moralised, and harangued, he had rubbed his feet up and down and had fretted the nap off the Brussels carpet.

“I think,” remarked Philippa, “that we can turn it about, and by taking out one width and putting that under the bookcase and inserting the strip that was there in its room, we can save the expense of a new carpet. But—the engravings—those Landseers. What do you think of them, Ben, dear?”

She pointed to the two familiar engravings of the “Deer in Winter,” and “Dignity and Impudence.”

“Don’t you think, Ben, that one has got a little tired of those pictures?”

“My late wife did not object to them, they were so perfectly harmless.”

“But your coming wife does. We will have something more up-to-date in their room. By the way, I wonder how the ghosts are getting on. They have let us alone so far. I will run back and have a peep at them through the curtains.”

The lively girl left the dining apartment, and her husband-elect, studying the pictures to which Philippa had objected. Presently she returned.

“Oh, Ben! such fun!” she said, laughing. “My ghost has drawn up his chair close to that of the late Mrs. Woolfield, and is fondling her hand. But I believe that they are only talking goody-goody.”

“And now about the china,” said Mr. Woolfield. “It is in a closet near the pantry—that is to say, the best china. I will get a benzoline lamp, and we will examine it. We had it out only when Mrs. Woolfield had a party of her elect brothers and sisters. I fear a good deal is broken. I know that the soup tureen has lost a lid, and I believe we are short of vegetable dishes. How many plates remain I do not know. We had a parlourmaid, Dorcas, who was a sad smasher, but as she was one who had made her election sure, my late wife would not part with her.”

“And how are you off for glass?”

“The wine-glasses are fairly complete. I fancy the cut-glass decanters are in a bad way. My late wife chipped them, I really believe out of spite.”

It took the couple some time to go through the china and the glass.

“And the plate?” asked Philippa.

“Oh, that is right. All the real old silver is at the bank, as Kesiah preferred plated goods.”

“How about the kitchen utensils?”

“Upon my word I cannot say. We had a rather nice-looking cook, and so my late wife never allowed me to step inside the kitchen.”

“Is she here still?” inquired Philippa sharply.

“No; my wife, when she was dying, gave her the sack.”

“Bless me, Ben!” exclaimed Philippa. “It is growing dark. I have been here an age. I really must go home. I wonder the ghosts have not worried us. I’ll have another look at them.”

She tripped off.

In five minutes she was back. She stood for a minute looking at Mr. Woolfield, laughing so heartily that she had to hold her sides.

“What is it, Philippa?” he inquired.

“Oh, Ben! A happy release. They will never dare to show their faces again. They have eloped together.”

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)