Public Domain Text: Monkeys by E. F. Benson

Monkeys is a short story written by E. F. Benson. It was first published in the December 1933 issue of Weird Tales magazine.

The following year, the author included the story in his anthology, More Spook Stories.

In the years that followed, Monkeys was reprinted in many more horror anthologies, including Tales of the Dead (Bonanza Books/Crown Publishers) and Mummy Stories (Ballantine Books).

For reasons that will soon become clear, several of the anthologies had Egyptian mummies as the primary focus.

With more than 6000 words, Monkeys is one of the longer E. F. Benson stories. Told in the third-person, it’s set in part in England and partly in Egypt.

The central character is Dr Hugh Morris, who has a reputation for being one of the most dextrous and daring surgeons in the medical profession.

With the firm belief that the experiments he conducts benefit humanity, Morris doesn’t find it hard to justify the pain he causes animals during vivisection.

Early on in the story, Morris encounters an injured monkey and attempts radical spinal surgery.

Later in the story, he has further encounters with monkeys while holidaying in Egypt.

When he accompanies a friend to an Egyptian tomb, Morris notices the mummified corpse inside had undergone a highly advanced surgical procedure similar to the one he performed on the monkey. The most amazing thing about this is, unlike the monkey he treated, the ancient Egyptian had apparently lived for many more years after the surgery.

His fascination leads Morris to make the biggest mistake of his life.

About E. F. Benson

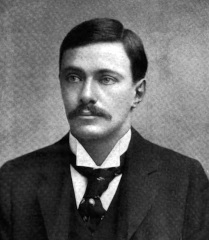

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

Monkeys

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

Dr. Hugh Morris, while still in the early thirties of his age, had justly earned for himself the reputation of being one of the most dexterous and daring surgeons in his profession, and both in his private practice and in his voluntary work at one of the great London hospitals his record of success as an operator was unparalleled among his colleagues. He believed that vivisection was the most fruitful means of progress in the science of surgery, holding, rightly or wrongly, that he was justified in causing suffering to animals, though sparing them all possible pain, if thereby he could reasonably hope to gain fresh knowledge about similar operations on human beings which would save life or mitigate suffering; the motive was good, and the gain already immense. But he had nothing but scorn for those who, for their own amusement, took out packs of hounds to run foxes to death, or matched two greyhounds to see which would give the death-grip to a single terrified hare: that, to him, was wanton torture, utterly unjustifiable. Year in and year out, he took no holiday at all, and for the most part he occupied his leisure, when the day’s work was over, in study.

He and his friend Jack Madden were dining together one warm October night at his house looking on to Regent’s Park. The windows of his drawing-room on the ground-floor were open, and they sat smoking, when dinner was done, on the broad window-seat. Madden was starting next day for Egypt, where he was engaged in archæological work, and he had been vainly trying to persuade Morris to join him for a month up the Nile, where he would be engaged throughout the winter in the excavation of a newly-discovered cemetery across the river from Luxor, near Medinet Habu. But it was no good.

“When my eye begins to fail and my fingers to falter,” said Morris, “it will be time for me to think of taking my ease. What do I want with a holiday? I should be pining to get back to my work all the time. I like work better than loafing. Purely selfish.”

“Well, be unselfish for once,” said Madden. “Besides, your work would benefit. It can’t be good for a man never to relax. Surely freshness is worth something.”

“Precious little if you’re as strong as I am. I believe in continual concentration if one wants to make progress. One may be tired, but why not? I’m not tired when I’m actually engaged on a dangerous operation, which is what matters. And time’s so short. Twenty years from now I shall be past my best, and I’ll have my holiday then, and when my holiday is over, I shall fold my hands and go to sleep for ever and ever. Thank God, I’ve got no fear that there’s an after-life. The spark of vitality that has animated us burns low and then goes out like a windblown candle, and as for my body, what do I care what happens to that when I have done with it? Nothing will survive of me except some small contribution I may have made to surgery, and in a few years’ time that will be superseded. But for that I perish utterly.”

Madden squirted some soda into his glass.

“Well, if you’ve quite settled that—” he began.

“I haven’t settled it, science has,” said Morris. “The body is transmuted into other forms, worms batten on it, it helps to feed the grass, and some animal consumes the grass. But as for the survival of the individual spirit of a man, show me one tittle of scientific evidence to support it. Besides, if it did survive, all the evil and malice in it must surely survive too. Why should the death of the body purge that away? It’s a nightmare to contemplate such a thing, and oddly enough, unhinged people like spiritualists want to persuade us for our consolation that the nightmare is true. But odder still are those old Egyptians of yours, who thought that there was something sacred about their bodies, after they were quit of them. And didn’t you tell me that they covered their coffins with curses on anyone who disturbed their bones?”

“Constantly,” said Madden. “It’s the general rule in fact. Marrowy curses written in hieroglyphics on the mummy-case or carved on the sarcophagus.”

“But that’s not going to deter you this winter from opening as many tombs as you can find, and rifling from them any objects of interest or value.”

Madden laughed.

“Certainly it isn’t,” he said. “I take out of the tombs all objects of art, and I unwind the mummies to find and annex their scarabs and jewellery. But I make an absolute rule always to bury the bodies again. I don’t say that I believe in the power of those curses, but anyhow a mummy in a museum is an indecent object.”

“But if you found some mummied body with an interesting malformation, wouldn’t you send it to some anatomical institute?” asked Morris.

“It has never happened to me yet,” said Madden, “but I’m pretty sure I shouldn’t.”

“Then you’re a superstitious Goth and an anti-educational Vandal,” remarked Morris. “Hullo, what’s that?” He leant out of the window as he spoke. The light from the room vividly illuminated the square of lawn outside, and across it was crawling the small twitching shape of some animal. Hugh Morris vaulted out of the window, and presently returned, carrying carefully in his spread hands a little grey monkey, evidently desperately injured. Its hind legs were stiff and outstretched as if it was partially paralysed.

Morris ran his soft deft fingers over it.

“What’s the matter with the little beggar, I wonder,” he said. “Paralysis of the lower limbs: it looks like some lesion of the spine.”

The monkey lay quite still, looking at him with anguished appealing eyes as he continued his manipulation.

“Yes, I thought so,” he said. “Fracture of one of the lumbar vertebræ. What luck for me! It’s a rare injury, but I’ve often wondered…. And perhaps luck for the monkey too, though that’s not very probable. If he was a man and a patient of mine, I shouldn’t dare to take the risk. But, as it is …”

Jack Madden started on his southward journey next day, and by the middle of November was at work on this newly-discovered cemetery. He and another Englishman were in charge of the excavation, under the control of the Antiquity Department of the Egyptian Government. In order to be close to their work and to avoid the daily ferrying across the Nile from Luxor, they hired a bare roomy native house in the adjoining village of Gurnah. A reef of low sandstone cliff ran northwards from here towards the temple and terraces of Deir-el-Bahari, and it was in the face of this and on the level below it that the ancient graveyard lay. There was much accumulation of sand to be cleared away before the actual exploration of the tombs could begin, but trenches cut below the foot of the sandstone ridge showed that there was an extensive area to investigate.

The more important sepulchres, they found, were hewn in the face of this small cliff: many of these had been rifled in ancient days, for the slabs forming the entrances into them had been split, and the mummies unwound, but now and then Madden unearthed some tomb that had escaped these marauders, and in one he found the sarcophagus of a priest of the nineteenth dynasty, and that alone repaid weeks of fruitless work. There were nearly a hundred ushaptiu figures of the finest blue glaze; there were four alabaster vessels in which had been placed the viscera of the dead man removed before embalming: there was a table of which the top was inlaid with squares of variously coloured glass, and the legs were of carved ivory and ebony: there were the priest’s sandals adorned with exquisite silver filagree: there was his staff of office inlaid with a diaper-pattern of cornelian and gold, and on the head of it, forming the handle, was the figure of a squatting cat, carved in amethyst, and the mummy, when unwound, was found to be decked with a necklace of gold plaques and onyx beads. All these were sent down to the Gizeh Museum at Cairo, and Madden reinterred the mummy at the foot of the cliff below the tomb. He wrote to Hugh Morris describing this find, and laying stress on the unbroken splendour of these crystalline winter days, when from morning to night the sun cruised across the blue, and on the cool nights when the stars rose and set on the vapourless rim of the desert. If by chance Hugh should change his mind, there was ample room for him in this house at Gurnah, and he would be very welcome.

A fortnight later Madden received a telegram from his friend. It stated that he had been unwell and was starting at once by long sea to Port Said, and would come straight up to Luxor. In due course he announced his arrival at Cairo and Madden went across the river next day to meet him: it was reassuring to find him as vital and active as ever, the picture of bronzed health. The two were alone that night, for Madden’s colleague had gone for a week’s trip up the Nile, and they sat out, when dinner was done, in the enclosed courtyard adjoining the house. Till then Madden had shied off the subject of himself and his health.

“Now I may as well tell you what’s been amiss with me,” he said, “for I know I look a fearful fraud as an invalid, and physically I’ve never been better in my life. Every organ has been functioning perfectly except one, but something suddenly went wrong there just once. It was like this.”

He paused a moment.

“After you left,” he said, “I went on as usual for another month or so, very busy, very serene and, I may say, very successful. Then one morning I arrived at the hospital when there was one perfectly ordinary but major operation waiting for me. The patient, a man, was wheeled into the theatre anæsthetized, and I was just about to make the first incision into the abdomen, when I saw that there was sitting on his chest a little grey monkey. It was not looking at me, but at the fold of skin which I held between my thumb and finger. I knew, of course, that there was no monkey there, and that what I saw was a hallucination, and I think you’ll agree that there was nothing much wrong with my nerves when I tell you that I went through the operation with clear eyes and an unshaking hand. I had to go on: there was no choice about the matter. I couldn’t say: ‘Please take that monkey away,’ for I knew there was no monkey there. Nor could I say: ‘Somebody else must do this, as I have a distressing hallucination that there is a monkey sitting on the patient’s chest.’ There would have been an end of me as a surgeon and no mistake. All the time I was at work it sat there absorbed for the most part in what I was doing and peering into the wound, but now and then it looked up at me, and chattered with rage. Once it fingered a spring-forceps which clipped a severed vein, and that was the worst moment of all. At the end it was carried out still balancing itself on the man’s chest…. I think I’ll have a drink. Strongish, please…. Thanks.”

“A beastly experience,” he said when he had drunk. “Then I went straight away from the hospital to consult my old friend Robert Angus, the alienist and nerve-specialist, and told him exactly what had happened to me. He made several tests, he examined my eyes, tried my reflexes, took my blood-pressure: there was nothing wrong with any of them. Then he asked me questions about my general health and manner of life, and among these questions was one which I am sure has already occurred to you, namely, had anything occurred to me lately, or even remotely, which was likely to make me visualize a monkey. I told him that a few weeks ago a monkey with a broken lumbar vertebra had crawled on to my lawn, and that I had attempted an operation—binding the broken vertebra with wire—which had occurred to me before as a possibility. You remember the night, no doubt?”

“Perfectly,” said Madden, “I started for Egypt next day. What happened to the monkey, by the way?”

“It lived for two days: I was pleased, because I had expected it would die under the anæsthetic, or immediately afterwards from shock. To get back to what I was telling you. When Angus had asked all his questions, he gave me a good wigging. He said that I had persistently overtaxed my brain for years, without giving it any rest or change of occupation, and that if I wanted to be of any further use in the world, I must drop my work at once for a couple of months. He told me that my brain was tired out and that I had persisted in stimulating it. A man like me, he said, was no better than a confirmed drunkard, and that, as a warning, I had had a touch of an appropriate delirium tremens. The cure was to drop work, just as a drunkard must drop drink. He laid it on hot and strong: he said I was on the verge of a breakdown, entirely owing to my own foolishness, but that I had wonderful physical health, and that if I did break down I should be a disgrace. Above all—and this seemed to me awfully sound advice—he told me not to attempt to avoid thinking about what had happened to me. If I kept my mind off it, I should be perhaps driving it into the subconscious, and then there might be bad trouble. ‘Rub it in: think what a fool you’ve been,’ he said. ‘Face it, dwell on it, make yourself thoroughly ashamed of yourself.’ Monkeys, too: I wasn’t to avoid the thought of monkeys. In fact, he recommended me to go straight away to the Zoological Gardens, and spend an hour in the monkey-house.”

“Odd treatment,” interrupted Madden.

“Brilliant treatment. My brain, he explained, had rebelled against its slavery, and had hoisted a red flag with the device of a monkey on it. I must show it that I wasn’t frightened at its bogus monkeys. I must retort on it by making myself look at dozens of real ones which could bite and maul you savagely, instead of one little sham monkey that had no existence at all. At the same time I must take the red flag seriously, recognize there was danger, and rest. And he promised me that sham monkeys wouldn’t trouble me again. Are there any real ones in Egypt, by the way?”

“Not so far as I know,” said Madden. “But there must have been once, for there are many images of them in tombs and temples.”

“That’s good. We’ll keep their memory green and my brain cool. Well, there’s my story. What do you think of it?”

“Terrifying,” said Madden. “But you must have got nerves of iron to get through that operation with the monkey watching.”

“A hellish hour. Out of some disordered slime in my brain there had crawled this unbidden thing, which showed itself, apparently substantial, to my eyes. It didn’t come from outside: my eyes hadn’t told my brain that there was a monkey sitting on the man’s chest, but my brain had told my eyes so, making fools of them. I felt as if someone whom I absolutely trusted had played me false. Then again I have wondered whether some instinct in my subconscious mind revolted against vivisection. My reason says that it is justified, for it teaches us how pain can be relieved and death postponed for human beings. But what if my subconscious persuaded my brain to give me a good fright, and reproduce before my eyes the semblance of a monkey, just when I was putting into practice what I had learned from dealing out pain and death to animals?”

He got up suddenly.

“What about bed?” he said. “Five hours’ sleep was enough for me when I was at work, but now I believe I could sleep the clock round every night.”

Young Wilson, Madden’s colleague in the excavations, returned next day and the work went steadily on. One of them was on the spot to start it soon after sunrise, and either one or both of them were superintending it, with an interval of a couple of hours at noon, until sunset. When the mere work of clearing the face of the sandstone cliff was in progress and of carting away the silted soil, the presence of one of them sufficed, for there was nothing to do but to see that the workmen shovelled industriously, and passed regularly with their baskets of earth and sand on their shoulders to the dumping-grounds, which stretched away from the area to be excavated, in lengthening peninsulas of trodden soil. But, as they advanced along the sandstone ridge, there would now and then appear a chiselled smoothness in the cliff and then both must be alert. There was great excitement to see if, when they exposed the hewn slab that formed the door into the tomb, it had escaped ancient marauders, and still stood in place and intact for the modern to explore. But now for many days they came upon no sepulchre that had not already been opened. The mummy, in these cases, had been unwound in the search for necklaces and scarabs, and its scattered bones lay about. Madden was always at pains to reinter these.

At first Hugh Morris was assiduous in watching the excavations, but as day after day went by without anything of interest turning up, his attendance grew less frequent: it was too much of a holiday to watch the day-long removal of sand from one place to another. He visited the Tomb of the Kings, he went across the river and saw the temples at Karnak, but his appetite for antiquities was small. On other days he rode in the desert, or spent the day with friends at one of the Luxor hotels. He came home from there one evening in rare good spirits, for he had played lawn-tennis with a woman on whom he had operated for malignant tumour six months before and she had skipped about the court like a two-year-old. “God, how I want to be at work again,” he exclaimed. “I wonder whether I ought not to have stuck it out, and defied my brain to frighten me with bogies.”

The weeks passed on, and now there were but two days left before his return to England, where he hoped to resume work at once: his tickets were taken and his berth booked. As he sat over breakfast that morning with Wilson, there came a workman from the excavation, with a note scribbled in hot haste by Madden, to say that they had just come upon a tomb which seemed to be unrifled, for the slab that closed it was in place and unbroken. To Wilson, the news was like the sight of a sail to a marooned mariner, and when, a quarter of an hour later, Morris followed him, he was just in time to see the slab prised away. There was no sarcophagus within, for the rock walls did duty for that, but there lay there, varnished and bright in hue as if painted yesterday, the mummy-case roughly following the outline of the human form. By it stood the alabaster vases containing the entrails of the dead, and at each corner of the sepulchre there were carved out of the sandstone rock, forming, as it were, pillars to support the roof, thick-set images of squatting apes. The mummy-case was hoisted out and carried away by workmen on a bier of boards into the courtyard of the excavators’ house at Gurnah, for the opening of it and the unwrapping of the dead.

They got to work that evening directly they had fed: the face painted on the lid was that of a girl or young woman, and presently deciphering the hieroglyphic inscription, Madden read out that within lay the body of A-pen-ara, daughter of the overseer of the cattle of Senmut.

“Then follow the usual formulas,” he said. “Yes, yes … ah, you’ll be interested in this, Hugh, for you asked me once about it. A-pen-ara curses any who desecrates or meddles with her bones, and should anyone do so, the guardians of her sepulchre will see to him, and he shall die childless and in panic and agony; also the guardians of her sepulchre will tear the hair from his head and scoop his eyes from their sockets, and pluck the thumb from his right hand, as a man plucks the young blade of corn from its sheath.”

Morris laughed.

“Very pretty little attentions,” he said. “And who are the guardians of this sweet young lady’s sepulchre? Those four great apes carved at the corners?”

“No doubt. But we won’t trouble them, for to-morrow I shall bury Miss A-pen-ara’s bones again with all decency in the trench at the foot of her tomb. They’ll be safer there, for if we put them back where we found them, there would be pieces of her hawked about by half the donkey-boys in Luxor in a few days. ‘Buy a mummy hand, lady?… Foot of a Gyppy Queen, only ten piastres, gentlemen’ … Now for the unwinding.”

It was dark by now, and Wilson fetched out a paraffin lamp, which burned unwaveringly in the still air. The lid of the mummy-case was easily detached, and within was the slim, swaddled body. The embalming had not been very thoroughly done, for all the skin and flesh had perished from the head, leaving only bones of the skull stained brown with bitumen. Round it was a mop of hair, which with the ingress of the air subsided like a belated soufflé, and crumbled into dust. The cloth that swathed the body was as brittle, but round the neck, still just holding together, was a collar of curious and rare workmanship: little ivory figures of squatting apes alternated with silver beads. But again a touch broke the thread that strung them together, and each had to be picked out singly. A bracelet of scarabs and cornelians still clasped one of the fleshless wrists, and then they turned the body over in order to get at the members of the necklace which lay beneath the nape. The rotted mummy-cloth fell away altogether from the back, disclosing the shoulder-blades and the spine down as far as the pelvis. Here the embalming had been better done, for the bones still held together with remnants of muscle and cartilage.

Hugh Morris suddenly sprang to his feet.

“My God, look there!” he cried, “one of the lumbar vertebræ, there at the base of the spine, has been broken and clamped together with a metal band. To hell with your antiquities: let me come and examine something much more modern than any of us!”

He pushed Jack Madden aside, and peered at this marvel of surgery.

“Put the lamp closer,” he said, as if directing some nurse at an operation. “Yes: that vertebra has been broken right across and has been clamped together. No one has ever, as far as I know, attempted such an operation except myself, and I have only performed it on that little paralysed monkey that crept into my garden one night. But some Egyptian surgeon, more than three thousand years ago, performed it on a woman. And look, look! She lived afterwards, for the broken vertebra put out that bony efflorescence of healing which has encroached over the metal band. That’s a slow process, and it must have taken place during her lifetime, for there is no such energy in a corpse. The woman lived long: probably she recovered completely. And my wretched little monkey only lived two days and was dying all the time.”

Those questing hawk-visioned fingers of the surgeon perceived more finely than actual sight, and now he closed his eyes as the tip of them felt their way about the fracture in the broken vertebra and the clamping metal band.

“The band doesn’t encircle the bone,” he said, “and there are no studs attaching it. There must have been a spring in it, which, when it was clasped there, kept it tight. It has been clamped round the bone itself: the surgeon must have scraped the vertebra clean of flesh before he attached it. I would give two years of my life to have looked on, like a student, at that masterpiece of skill, and it was worth while giving up two months of my work only to have seen the result. And the injury itself is so rare, this breaking of a spinal vertebra. To be sure, the hangman does something of the sort, but there’s no mending that! Good Lord, my holiday has not been a waste of time!”

Madden settled that it was not worth while to send the mummy-case to the museum at Gizeh, for it was of a very ordinary type, and when the examination was over they lifted the body back into it, for reinterment next day. It was now long after midnight and presently the house was dark.

Hugh Morris slept on the ground-floor in a room adjoining the yard where the mummy-case lay. He remained long awake marvelling at that astonishing piece of surgical skill performed, according to Madden, some thirty-five centuries ago. So occupied had his mind been with homage that not till now did he realize that the tangible proof and witness of the operation would to-morrow be buried again and lost to science. He must persuade Madden to let him detach at least three of the vertebræ, the mended one and those immediately above and below it, and take them back to England as demonstration of what could be done: he would lecture on his exhibit and present it to the Royal College of Surgeons for example and incitement. Other trained eyes beside his own must see what had been successfully achieved by some unknown operator in the nineteenth dynasty…. But supposing Madden refused? He always made a point of scrupulously reburying these remains: it was a principle with him, and no doubt some superstition-complex—the hardest of all to combat with because of its sheer unreasonableness—was involved. Briefly, it was impossible to risk the chance of his refusal.

He got out of bed, listened for a moment by his door, and then softly went out into the yard. The moon had risen, for the brightness of the stars was paled, and though no direct rays shone into the walled enclosure, the dusk was dispersed by the toneless luminosity of the sky, and he had no need of a lamp. He drew the lid off the coffin, and folded back the tattered cerements which Madden had replaced over the body. He had thought that those lower vertebræ of which he was determined to possess himself would be easily detached, so far perished were the muscle and cartilage which held them together, but they cohered as if they had been clamped, and it required the utmost force of his powerful fingers to snap the spine, and as he did so the severed bones cracked as with the noise of a pistol-shot. But there was no sign that anyone in the house had heard it, there came no sound of steps, nor lights in the windows. One more fracture was needed, and then the relic was his. Before he replaced the ragged cloths he looked again at the stained fleshless bones. Shadow dwelt in the empty eye-sockets, as if black sunken eyes still lay there, fixedly regarding him, the lipless mouth snarled and grimaced. Even as he looked some change came over its aspect, and for one brief moment he fancied that there lay staring up at him the face of a great brown ape. But instantly that illusion vanished, and replacing the lid he went back to his room.

The mummy-case was reinterred next day, and two evenings after Morris left Luxor by the night train for Cairo, to join a homeward-bound P. & O. at Port Said. There were some hours to spare before his ship sailed, and having deposited his luggage, including a locked leather despatch-case, on board, he lunched at the Café Tewfik near the quay. There was a garden in front of it with palm trees and trellises gaily clad in bougainvillias: a low wooden rail separated it from the street, and Morris had a table close to this. As he ate he watched the polychromatic pageant of Eastern life passing by: there were Egyptian officials in broad-cloth frock coats and red fezzes; barefooted splay-toed fellahin in blue gabardines; veiled women in white making stealthy eyes at passers-by; half-naked gutter-snipes, one with a sprig of scarlet hibiscus behind his ear; travellers from India with solar topees and an air of aloof British superiority; dishevelled sons of the Prophet in green turbans; a stately sheik in a white burnous; French painted ladies of a professional class with lace-rimmed parasols and provocative glances; a wild-eyed dervish in an accordion-pleated skirt, chewing betel-nut and slightly foaming at the mouth. A Greek boot-black with box adorned with brass plaques tapped his brushes on it to encourage customers, an Egyptian girl squatted in the gutter beside a gramophone, steamers passing into the Canal hooted on their syrens.

Then at the edge of the pavement there sauntered by a young Italian harnessed to a barrel-organ: with one hand he ground out a popular air by Verdi, in the other he held out a tin can for the tributes of music-lovers: a small monkey in a yellow jacket, tethered to his wrist, sat on the top of his instrument. The musician had come opposite the table where Morris sat: Morris liked the gay tinkling tune, and feeling in his pocket for a piastre, he beckoned to him. The boy grinned and stepped up to the rail.

Then suddenly the melancholy-eyed monkey leaped from its place on the organ and sprang on to the table by which Morris sat. It alighted there, chattering with rage in a crash of broken glass. A flower-vase was upset, a plate clattered on to the floor. Morris’s coffee-cup discharged its black contents on the tablecloth. Next moment the Italian had twitched the frenzied little beast back to him, and it fell head downwards on the pavement. A shrill hubbub arose, the waiter at Morris’s table hurried up with voluble execrations, a policeman kicked out at the monkey as it lay on the ground, the barrel-organ tottered and crashed on the roadway. Then all subsided again, and the Italian boy picked up the little body from the pavement. He held it out in his hands to Morris.

“E morto,” he said.

“Serve it right, too,” retorted Morris. “Why did it fly at me like that?”

He travelled back to London by long sea, and day after day that tragic little incident, in which he had had no responsible part, began to make a sort of colouring matter in his mind during those hours of lazy leisure on ship-board, when a man gives about an equal inattention to the book he reads and to what passes round him. Sometimes if the shadow of a seagull overhead slid across the deck towards him, there leaped into his brain, before his eyes could reassure him, the ludicrous fancy that this shadow was a monkey springing at him. One day they ran into a gale from the west: there was a crash of glass at his elbow as a sudden lurch of the ship upset a laden steward, and Morris jumped from his seat thinking that a monkey had leaped on to his table again. There was a cinematograph show in the saloon one evening, in which some naturalist exhibited the films he had taken of wild life in Indian jungles: when he put on the screen the picture of a company of monkeys swinging their way through the trees Morris involuntarily clutched the sides of his chair in hideous panic that lasted but a fraction of a second, until he recalled to himself that he was only looking at a film in the saloon of a steamer passing up the coast of Portugal. He came sleepy into his cabin one night and saw some animal crouching by the locked leather despatch-case. His breath caught in his throat before he perceived that this was a friendly cat which rose with gleaming eyes and arched its back.

These fantastic unreasonable alarms were disquieting. He had as yet no repetition of the hallucination that he saw a monkey, but some deep-buried “idea,” to cure which he had taken two months’ holiday, was still unpurged from his mind. He must consult Robert Angus again when he got home, and seek further advice. Probably that incident at Port Said had rekindled the obscure trouble, and there was this added to it, that he knew he was now frightened of real monkeys: there was terror sprouting in the dark of his soul. But as for it having any connection with his pilfered treasure, so rank and childish a superstition deserved only the ridicule he gave it. Often he unlocked his leather case and sat poring over that miracle of surgery which made practical again long-forgotten dexterities.

But it was good to be back in England. For the last three days of the voyage no menace had flashed out on him from the unknown dusks, and surely he had been disquieting himself in vain. There was a light mist lying over Regent’s Park on this warm March evening, and a drizzle of rain was falling. He made an appointment for the next morning with the specialist, he telephoned to the hospital that he had returned and hoped to resume work at once. He dined in very good spirits, talking to his manservant, and, as subsequently came out, he showed him his treasured bones, telling him that he had taken the relic from a mummy which he had seen unwrapped and that he meant to lecture on it. When he went up to bed he carried the leather case with him. Bed was comfortable after the ship’s berth, and through his open window came the soft hissing of the rain on to the shrubs outside.

His servant slept in the room immediately over his. A little before dawn he woke with a start, roused by horrible cries from somewhere close at hand. Then came words yelled out in a voice that he knew:

“Help! Help!” it cried. “O my God, my God! Ah—h—” and it rose to a scream again.

The man hurried down and clicked on the light in his master’s room as he entered. The cries had ceased: only a low moaning came from the bed. A huge ape with busy hands was bending over it; then taking up the body that lay there by the neck and the hips he bent it backwards and it cracked like a dry stick. Then it tore open the leather case that was on a table by the bedside, and with something that gleamed white in its dripping fingers it shambled to the window and disappeared.

A doctor arrived within half an hour, but too late. Handfuls of hair with flaps of skins attached had been torn from the head of the murdered man, both eyes were scooped out of their sockets, the right thumb had been plucked off the hand, and the back was broken across the lower vertebræ.

Nothing has since come to light which could rationally explain the tragedy. No large ape had escaped from the neighbouring Zoological Gardens, or, as far as could be ascertained, from elsewhere, nor was the monstrous visitor of that night ever seen again. Morris’s servant had only had the briefest sight of it, and his description of it at the inquest did not tally with that of any known simian type. And the sequel was even more mysterious, for Madden, returning to England at the close of the season in Egypt, had asked Morris’s servant exactly what it was that his master had shown him the evening before as having been taken by him from a mummy which he had seen unwrapped, and had got from him a sufficiently conclusive account of it. Next autumn he continued his excavations in the cemetery at Gurnah, and he disinterred once more the mummy-case of A-pen-ara and opened it. But the spinal vertebræ were all in place and complete: one had round it the silver clip which Morris had hailed as a unique achievement in surgery.

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)