The Mother of Pansies by Sabine Baring-Gould

The Mother of Pansies is a short story by Sabine Baring-Gould. As is the case with most of his stories, it was first published in his short story anthology A Book of Ghosts (1904).

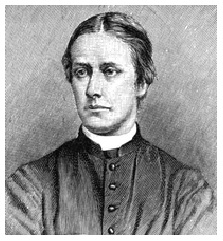

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

The Mother of Pansies by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

Anna Voss, of Siebenstein, was the prettiest girl in her village. Never was she absent from a fair or a dance. No one ever saw her abroad anything but merry. If she had her fits of bad temper, she kept them for her mother, in the secrecy of the house. Her voice was like that of the lark, and her smile like the May morning. She had plenty of suitors, for she was possessed of what a young peasant desires more in a wife than beauty, and that is money.

But of all the young men who hovered about her, and sought her favour, none was destined to win it save Joseph Arler, the ranger, a man in a government position, whose duty was to watch the frontier against smugglers, and to keep an eye on the game against poachers.

The eve of the marriage had come.

One thing weighed on the pleasure-loving mind of Anna. She dreaded becoming a mother of a family which would keep her at home, and occupy her from morn to eve in attendance on her children, and break the sweetness of her sleep at night.

So she visited an old hag named Schändelwein, who was a reputed witch, and to whom she confided her trouble.

The old woman said that she had looked into the mirror of destiny, before Anna arrived, and she had seen that Providence had ordained that Anna should have seven children, three girls and four boys, and that one of the latter was destined to be a priest.

But Mother Schändelwein had great powers; she could set at naught the determinations of Providence; and she gave to Anna seven pips, very much like apple-pips, which she placed in a cornet of paper; and she bade her cast these one by one into the mill-race, and as each went over the mill-wheel, it ceased to have a future, and in each pip was a child’s soul.

So Anna put money into Mother Schändelwein’s hand and departed, and when it was growing dusk she stole to the wooden bridge over the mill-stream, and dropped in one pip after another. As each fell into the water she heard a little sigh.

But when it came to casting in the last of the seven she felt a sudden qualm, and a battle in her soul.

However, she threw it in, and then, overcome by an impulse of remorse, threw herself into the stream to recover it, and as she did so she uttered a cry.

But the water was dark, the floating pip was small, she could not see it, and the current was rapidly carrying her to the mill-wheel, when the miller ran out and rescued her.

On the following morning she had completely recovered her spirits, and laughingly told her bridesmaids how that in the dusk, in crossing the wooden bridge, her foot had slipped, she had fallen into the stream, and had been nearly drowned. “And then,” added she, “if I really had been drowned, what would Joseph have done?”

The married life of Anna was not unhappy. It could hardly be that in association with so genial, kind, and simple a man as Joseph. But it was not altogether the ideal happiness anticipated by both. Joseph had to be much away from home, sometimes for days and nights together, and Anna found it very tedious to be alone. And Joseph might have calculated on a more considerate wife. After a hard day of climbing and chasing in the mountains, he might have expected that she would have a good hot supper ready for him. But Anna set before him whatever came to hand and cost least trouble. A healthy appetite is the best of sauces, she remarked.

Moreover, the nature of his avocation, scrambling up rocks and breaking through an undergrowth of brambles and thorns, produced rents and fraying of stockings and cloth garments. Instead of cheerfully undertaking the repairs, Anna grumbled over each rent, and put out his garments to be mended by others. It was only when repair was urgent that she consented to undertake it herself, and then it was done with sulky looks, muttered reproaches, and was executed so badly that it had to be done over again, and by a hired workwoman.

But Joseph’s nature was so amiable, and he was so fond of his pretty wife, that he bore with those defects, and turned off her murmurs with a joke, or sealed her pouting lips with a kiss.

There was one thing about Joseph that Anna could not relish. Whenever he came into the village, he was surrounded, besieged by the children. Hardly had he turned the corner into the square, before it was known that he was there, and the little ones burst out of their parents’ houses, broke from their sister nurse’s arms, to scamper up to Joseph and to jump about him. For Joseph somehow always had nuts or almonds or sweets in his pockets, and for these he made the children leap, or catch, or scramble, or sometimes beg, by putting a sweet on a boy’s nose and bidding him hold it there, till he said “Catch!”

Joseph had one particular favourite among all this crew, and that was a little lame boy with a white, pinched face, who hobbled about on crutches.

Him Joseph would single out, take him on his knee, seat himself on the steps of the village cross or of the churchyard, and tell him stories of his adventures, of the habits of the beasts of the forest.

Anna, looking out of her window, could see all this; and see how before Joseph set the poor cripple down, the child would throw its arms round his neck and kiss him.

Then Joseph would come home with his swinging step and joyous face.

Anna resented that his first attention should be given to the children, regarding it as her due, and she often showed her displeasure by the chill of her reception of her husband. She did not reproach him in set words, but she did not run to meet him, jump into his arms, and respond to his warm kisses.

Once he did venture on a mild expostulation. “Annerl, why do you not knit my socks or stocking-legs? Home-made is heart-made. It is a pity to spend money on buying what is poor stuff, when those made by you would not only last on my calves and feet, but warm the cockles of my heart.”

To which she replied testily: “It is you who set the example of throwing money away on sweet things for those pestilent little village brats.”

One evening Anna heard an unusual hubbub in the square, shouts and laughter, not of children alone, but of women and men as well, and next moment into the house burst Joseph very red, carrying a cradle on his head.

“What is this fooling for?” asked Anna, turning crimson.

“An experiment, Annerl, dearest,” answered Joseph, setting down the cradle. “I have heard it said that a wife who rocks an empty cradle soon rocks a baby into it. So I have bought this and brought it to you. Rock, rock, rock, and when I see a little rosebud in it among the snowy linen, I shall cry for joy.”

Never before had Anna known how dull and dead life could be in an empty house. When she had lived with her mother, that mother had made her do much of the necessary work of the house; now there was not much to be done, and there was no one to exercise compulsion.

If Anna ran out and visited her neighbours, they proved to be disinclined for a gossip. During the day they had to scrub and bake and cook, and in the evening they had their husbands and children with them, and did not relish the intrusion of a neighbour.

The days were weary days, and Anna had not the energy or the love of work to prompt her to occupy herself more than was absolutely necessary. Consequently, the house was not kept scrupulously clean. The glass and the pewter and the saucepans did not shine. The window-panes were dull. The house linen was unhemmed.

One evening Joseph sat in a meditative mood over the fire, looking into the red embers, and what was unusual with him, he did not speak.

Anna was inclined to take umbrage at this, when all at once he looked round at her with his bright pleasant smile and said, “Annerl! I have been thinking. One thing is wanted to make us supremely happy—a baby in the house. It has not pleased God to send us one, so I propose that we both go on pilgrimage to Mariahilf to ask for one.”

“Go yourself—I want no baby here,” retorted Anna.

A few days after this, like a thunderbolt out of a clear sky, came the great affliction on Anna of her husband’s death.

Joseph had been found shot in the mountains. He was quite dead. The bullet had pierced his heart. He was brought home borne on green fir-boughs interlaced, by four fellow-jägers, and they carried him into his house. He had, in all probability, met his death at the hand of smugglers.

With a cry of horror and grief Anna threw herself on Joseph’s body and kissed his pale lips. Now only did she realise how deeply all along she had loved him—now that she had lost him.

Joseph was laid in his coffin preparatory to the interment on the morrow. A crucifix and two candles stood at his head on a little table covered with a white cloth. On a stool at his feet was a bowl containing holy water and a sprig of rue.

A neighbour had volunteered to keep company with Anna during the night, but she had impatiently, without speaking, repelled the offer. She would spend the last night that he was above ground alone with her dead—alone with her thoughts.

And what were those thoughts?

Now she remembered how indifferent she had been to his wishes, how careless of his comforts; how little she had valued his love, had appreciated his cheerfulness, his kindness, his forbearance, his equable temper.

Now she recalled studied coldness on her part, sharp words, mortifying gestures, outbursts of unreasoning and unreasonable petulance.

Now she recalled Joseph scattering nuts among the children, addressing kind words to old crones, giving wholesome advice to giddy youths.

She remembered now little endearments shown to her, the presents brought her from the fair, the efforts made to cheer her with his pleasant stories and quaint jokes. She heard again his cheerful voice as he strove to interest her in his adventures of the chase.

As she thus sat silent, numbed by her sorrow, in the faint light cast by the two candles, with the shadow of the coffin lying black on the floor at her feet, she heard a stumping without; then a hand was laid on the latch, the door was timidly opened, and in upon his crutches came the crippled boy. He looked wistfully at her, but she made no sign, and then he hobbled to the coffin and burst into tears, and stooped and kissed the brow of his dead friend.

Leaning on his crutches, he took his rosary and said the prayers for the rest of her and his Joseph’s soul; then shuffled awkwardly to the foot, dipped the spray of rue, and sprinkled the dead with the blessed water.

Next moment the ungainly creature was stumping forth, but after he had passed through the door, he turned, looked once more towards the dead, put his hand to his lips, and wafted to it his final farewell.

Anna now took her beads and tried to pray, but her prayers would not leave her lips; they were choked and driven back by the thoughts which crowded up and bewildered her. The chain fell from her fingers upon her lap, lay there neglected, and then slipped to the floor. How the time passed she knew not, neither did she care. The clock ticked, and she heard it not; the hours sounded, and she regarded them not till in at her ear and through her brain came clear the call of the wooden cuckoo announcing midnight.

Her eyes had been closed. Now suddenly she was roused, and they opened and saw that all was changed.

The coffin was gone, but by her instead was the cradle that years ago Joseph had brought home, and which she had chopped up for firewood. And now in that cradle lay a babe asleep, and with her foot she rocked it, and found a strange comfort in so doing.

She was conscious of no sense of surprise, only a great welling up of joy in her heart. Presently she heard a feeble whimper and saw a stirring in the cradle; little hands were put forth gropingly. Then she stooped and lifted the child to her lap, and clasped it to her heart. Oh, how lovely was that tiny creature! Oh, how sweet in her ears its appealing cry! As she held it to her bosom the warm hands touched her throat, and the little lips were pressed to her bosom. She pressed it to her. She had entered into a new world, a world of love and light and beauty and happiness unspeakable. Oh! the babe—the babe—the babe! She laughed and cried, and cried and laughed and sobbed for very exuberance of joy. It brought warmth to her heart, it made every vein tingle, it ingrained her brain with pride. It was hers!—her own!—her very own! She could have been content to spend an eternity thus, with that little one close, close to her heart.

Then as suddenly all faded away—the child in her arms was gone as a shadow; her tears congealed, her heart was cramped, and a voice spoke within her: “It is not, because you would not. You cast the soul away, and it went over the mill-wheel.”

Wild with terror, uttering a despairing cry, she started up, straining her arms after the lost child, and grasping nothing. She looked about her. The light of the candles flickered over the face of her dead Joseph. And tick, tick, tick went the clock.

She could endure this no more. She opened the door to leave the room, and stepped into the outer chamber and cast herself into a chair. And lo! it was no more night. The sun, the red evening sun, shone in at the window, and on the sill were pots of pinks and mignonette that filled the air with fragrance.

And there at her side stood a little girl with shining fair hair, and the evening sun was on it like the glory about a saint. The child raised its large blue eyes to her, pure innocent eyes, and said: “Mother, may I say my Catechism and prayers before I go to bed?”

Then Anna answered and said: “Oh, my darling! My dearest Bärbchen! All the Catechism is comprehended in this: Love God, fear God, always do what is your duty. Do His will, and do not seek only your own pleasure and ease. And this will give you peace—peace—peace.”

The little girl knelt and laid her golden head on her folded hands upon Anna’s knee and began: “God bless dear father, and mother, and all my dear brothers and sisters.”

Instantly a sharp pang as a knife went through the heart of Anna, and she cried: “Thou hast no father and no mother and no brothers and no sisters, for thou art not, because I would not have thee. I cast away thy soul, and it went over the mill-wheel.”

The cuckoo called one. The child had vanished. But the door was thrown open, and in the doorway stood a young couple—one a youth with fair hair and the down of a moustache on his lip, and oh, in face so like to the dead Joseph. He held by the hand a girl, in black bodice and with white sleeves, looking modestly on the ground. At once Anna knew what this signified. It was her son Florian come to announce that he was engaged, and to ask his mother’s sanction.

Then said the young man, as he came forward leading the girl: “Mother, sweetest mother, this is Susie, the baker’s daughter, and child of your old and dear friend Vronie. We love one another; we have loved since we were little children together at school, and did our lessons out of one book, sitting on one bench. And, mother, the bakehouse is to be passed on to me and to Susie, and I shall bake for all the parish. The good Jesus fed the multitude, distributing the loaves through the hands of His apostles. And I shall be His minister feeding His people here. Mother, give us your blessing.”

Then Florian and the girl knelt to Anna, and with tears of happiness in her eyes she raised her hands over them. But ere she could touch them all had vanished. The room was dark, and a voice spake within her: “There is no Florian; there would have been, but you would not. You cast his soul into the water, and it passed away for ever over the mill-wheel.”

In an agony of terror Anna sprang from her seat. She could not endure the room, the air stifled her; her brain was on fire. She rushed to the back door that opened on a kitchen garden, where grew the pot-herbs and cabbages for use, tended by Joseph when he returned from his work in the mountains.

But she came forth on a strange scene. She was on a battlefield. The air was charged with smoke and the smell of gunpowder. The roar of cannon and the rattle of musketry, the cries of the wounded, and shouts of encouragement rang in her ears in a confused din.

As she stood, panting, her hands to her breast, staring with wondering eyes, before her charged past a battalion of soldiers, and she knew by their uniforms that they were Bavarians. One of them, as he passed, turned his face towards her; it was the face of an Arler, fired with enthusiasm, she knew it; it was that of her son Fritz.

Then came a withering volley, and many of the gallant fellows fell, among them he who carried the standard. Instantly, Fritz snatched it from his hand, waved it over his head, shouted, “Charge, brothers, fill up the ranks! Charge, and the day is ours!”

Then the remnant closed up and went forward with bayonets fixed, tramp, tramp. Again an explosion of firearms and a dense cloud of smoke rolled before her and she could not see the result.

She waited, quivering in every limb, holding her breath—hoping, fearing, waiting. And as the smoke cleared she saw men carrying to the rear one who had been wounded, and in his hand he grasped the flag. They laid him at Anna’s feet, and she recognised that it was her Fritz. She fell on her knees, and snatching the kerchief from her throat and breast, strove to stanch the blood that welled from his heart. He looked up into her eyes, with such love in them as made her choke with emotion, and he said faintly: “Mütterchen, do not grieve for me; we have stormed the redoubt, the day is ours. Be of good cheer. They fly, they fly, those French rascals! Mother, remember me—I die for the dear Fatherland.”

And a comrade standing by said: “Do not give way to your grief, Anna Arler; your son has died the death of a hero.”

Then she stooped over him, and saw the glaze of death in his eyes, and his lips moved. She bent her ear to them and caught the words: “I am not, because you would not. There is no Fritz; you cast my soul into the brook and I was carried over the mill-wheel.”

All passed away, the smell of the powder, the roar of the cannon, the volumes of smoke, the cry of the battle, all—to a dead hush. Anna staggered to her feet, and turned to go back to her cottage, and as she opened the door, heard the cuckoo call two.

But, as she entered, she found herself to be, not in her own room and house—she had strayed into another, and she found herself not in a lone chamber, not in her desolate home, but in the midst of a strange family scene.

A woman, a mother, was dying. Her head reposed on her husband’s breast as he sat on the bed and held her in his arms.

The man had grey hair, his face was overflowed with tears, and his eyes rested with an expression of devouring love on her whom he supported, and whose brow he now and again bent over to kiss.

About the bed were gathered her children, ay, and also her grandchildren, quite young, looking on with solemn, wondering eyes on the last throes of her whom they had learned to cling to and love with all the fervour of their simple hearts. One mite held her doll, dangling by the arm, and the forefinger of her other hand was in her mouth. Her eyes were brimming, and sobs came from her infant breast. She did not understand what was being taken from her, but she wept in sympathy with the rest.

Kneeling by the bed was the eldest daughter of the expiring woman, reciting the Litany of the Dying, and the sons and another daughter and a daughter-in-law repeated the responses in voices broken with tears.

When the recitation of the prayers ceased, there ensued for a while a great stillness, and all eyes rested on the dying woman. Her lips moved, and she poured forth her last petitions, that left her as rising flakes of fire, kindled by her pure and ardent soul. “O God, comfort and bless my dear husband, and ever keep Thy watchful guard over my children and my children’s children, that they may walk in the way that leads to Thee, and that in Thine own good time we may all—all be gathered in Thy Paradise together, united for evermore. Amen.”

A spasm contracted Anna’s heart. This woman with ecstatic, upturned gaze, this woman breathing forth her peaceful soul on her husband’s breast, was her own daughter Elizabeth, and in the fine outline of her features was Joseph’s profile.

All again was hushed. The father slowly rose and quitted his position on the bed, gently laid the head on the pillow, put one hand over the eyes that still looked up to heaven, and with the fingers of the other tenderly arranged the straggling hair on each side of the brow. Then standing and turning to the rest, with a subdued voice he said: “My children, it has pleased the Lord to take to Himself your dear mother and my faithful companion. The Lord’s will be done.”

Then ensued a great burst of weeping, and Anna’s eyes brimmed till she could see no more. The church bell began to toll for a departing spirit. And following each stroke there came to her, as the after-clang of the boom: “There is not, there has not been, an Elizabeth. There would have been all this—but thou wouldest it not. For the soul of thy Elizabeth thou didst send down the mill-stream and over the wheel.”

Frantic with shame, with sorrow, not knowing what she did, or whither she went, Anna made for the front door of the house, ran forth and stood in the village square.

To her unutterable amazement it was vastly changed. Moreover, the sun was shining brightly, and it gleamed over a new parish church, of cut white stone, very stately, with a gilded spire, with windows of wondrous lacework. Flags were flying, festoons of flowers hung everywhere. A triumphal arch of leaves and young birch trees was at the graveyard gate. The square was crowded with the peasants, all in their holiday attire.

Silent, Anna stood and looked around. And as she stood she heard the talk of the people about her.

One said: “It is a great thing that Johann von Arler has done for his native village. But see, he is a good man, and he is a great architect.”

“But why,” asked another, “do you call him Von Arler? He was the son of that Joseph the Jäger who was killed by the smugglers in the mountains.”

“That is true. But do you not know that the king has ennobled him? He has done such great things in the Residenz. He built the new Town Hall, which is thought to be the finest thing in Bavaria. He added a new wing to the Palace, and he has rebuilt very many churches, and designed mansions for the rich citizens and the nobles. But although he is such a famous man his heart is in the right place. He never forgets that he was born in Siebenstein. Look what a beautiful house he has built for himself and his family on the mountain-side. He is there in summer, and it is furnished magnificently. But he will not suffer the old, humble Arler cottage here to be meddled with. They say that he values it above gold. And this is the new church he has erected in his native village—that is good.”

“Oh! he is a good man is Johann; he was always a good and serious boy, and never happy without a pencil in his hand. You mark what I say. Some day hence, when he is dead, there will be a statue erected in his honour here in this market-place, to commemorate the one famous man that has been produced by Siebenstein. But see—see! Here he comes to the dedication of the new church.”

Then, through the throng advanced a blonde, middle-aged man, with broad forehead, clear, bright blue eyes, and a flowing light beard. All the men present plucked off their hats to him, and made way for him as he advanced. But, full of smiles, he had a hand and a warm pressure, and a kindly word and a question as to family concerns, for each who was near.

All at once his eye encountered that of Anna. A flash of recognition and joy kindled it up, and, extending his arms, he thrust his way towards her, crying: “My mother! my own mother!”

Then—just as she was about to be folded to his heart, all faded away, and a voice said in her soul: “He is no son of thine, Anna Arler. He is not, because thou wouldest not. He might have been, God had so purposed; but thou madest His purpose of none effect. Thou didst send his soul over the mill-wheel.”

And then faintly, as from a far distance, sounded in her ear the call of the cuckoo—three.

The magnificent new church had shrivelled up to the original mean little edifice Anna had known all her life. The square was deserted, the cold faint glimmer of coming dawn was visible over the eastern mountain-tops, but stars still shone in the sky.

With a cry of pain, like a wounded beast, Anna ran hither and thither seeking a refuge, and then fled to the one home and resting-place of the troubled soul—the church. She thrust open the swing-door, pushed in, sped over the uneven floor, and flung herself on her knees before the altar.

But see! before that altar stood a priest in a vestment of black-and-silver; and a serving-boy knelt on his right hand on a lower stage. The candles were lighted, for the priest was about to say Mass. There was a rustling of feet, a sound as of people entering, and many were kneeling, shortly after, on each side of Anna, and still they came on; she turned about and looked and saw a great crowd pressing in, and strange did it seem to her eyes that all—men, women, and children, young and old—seemed to bear in their faces something, a trace only in many, of the Arler or the Voss features. And the little serving-boy, as he shifted his position, showed her his profile—it was like her little brother who had died when he was sixteen.

Then the priest turned himself about, and said, “Oremus.” And she knew him—he was her own son—her Joseph, named after his dear father.

The Mass began, and proceeded to the “Sursum corda”—”Lift up your hearts!”—when the celebrant stood facing the congregation with extended arms, and all responded: “We lift them up unto the Lord.”

But then, instead of proceeding with the accustomed invocation, he raised his hands high above his head, with the palms towards the congregation, and in a loud, stern voice exclaimed—

“Cursed is the unfruitful field!”

“Amen.”

“Cursed is the barren tree!”

“Amen.”

“Cursed is the empty house!”

“Amen.”

“Cursed is the fishless lake!”

“Amen.”

“Forasmuch as Anna Arler, born Voss, might have been the mother of countless generations, as the sand of the seashore for number, as the stars of heaven for brightness, of generations unto the end of time, even of all of us now gathered together here, but she would not—therefore shall she be alone, with none to comfort her; sick, with none to minister to her; broken in heart, with none to bind up her wounds; feeble, and none to stay her up; dead, and none to pray for her, for she would not—she shall have an unforgotten and unforgettable past, and have no future; remorse, but no hope; she shall have tears, but no laughter—for she would not. Woe! woe! woe!”

He lowered his hands, and the tapers were extinguished, the celebrant faded as a vision of the night, the server vanished as an incense-cloud, the congregation disappeared, melting into shadows, and then from shadows to nothingness, without stirring from their places, and without a sound.

And Anna, with a scream of despair, flung herself forward with her face on the pavement, and her hands extended.

Two years ago, during the first week in June, an English traveller arrived at Siebenstein and put up at the “Krone,” where, as he was tired and hungry, he ordered an early supper. When that was discussed, he strolled forth into the village square, and leaned against the wall of the churchyard. The sun had set in the valley, but the mountain-peaks were still in the glory of its rays, surrounding the place as a golden crown. He lighted a cigar, and, looking into the cemetery, observed there an old woman, bowed over a grave, above which stood a cross, inscribed “Joseph Arler,” and she was tending the flowers on it, and laying over the arms of the cross a little wreath of heart’s-ease or pansy. She had in her hand a small basket. Presently she rose and walked towards the gate, by which stood the traveller.

As she passed, he said kindly to her: “Grüss Gott, Mütterchen.”

She looked steadily at him and replied: “Honoured sir! that which is past may be repented of, but can never be undone!” and went on her way.

He was struck with her face. He had never before seen one so full of boundless sorrow—almost of despair.

His eyes followed her as she walked towards the mill-stream, and there she took her place on the wooden bridge that crossed it, leaning over the handrail, and looking down into the water. An impulse of curiosity and of interest led him to follow her at a distance, and he saw her pick a flower, a pansy, out of her basket, and drop it into the current, which caught and carried it forward. Then she took a second, and allowed it to fall into the water. Then, after an interval, a third—a fourth; and he counted seven in all. After that she bowed her head on her hands; her grey hair fell over them, and she broke into a paroxysm of weeping.

The traveller, standing by the stream, saw the seven pansies swept down, and one by one pass over the revolving wheel and vanish.

He turned himself about to return to his inn, when, seeing a grave peasant near, he asked: “Who is that poor old woman who seems so broken down with sorrow?”

“That,” replied the man, “is the Mother of Pansies.”

“The Mother of Pansies!” he repeated.

“Well—it is the name she has acquired in the place. Actually, she is called Anna Arler, and is a widow. She was the wife of one Joseph Arler, a jäger, who was shot by smugglers. But that is many, many years ago. She is not right in her head, but she is harmless. When her husband was brought home dead, she insisted on being left alone in the night by him, before he was buried alone,—with his coffin. And what happened in that night no one knows. Some affirm that she saw ghosts. I do not know—she may have had Thoughts. The French word for these flowers is pensées—thoughts—and she will have none others. When they are in her garden she collects them, and does as she has done now. When she has none, she goes about to her neighbours and begs them. She comes here every evening and throws in seven—just seven, no more and no less—and then weeps as one whose heart would split. My wife on one occasion offered her forget-me-nots. ‘No,’ she said; ‘I cannot send forget-me-nots after those who never were, I can send only Pansies.'”

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)