Public Domain Text: The 9:30 Up-Train by Sabine Baring-Gould

The 9.30 Up-Train is a ghost story. It was first published in an 1863 edition of Once a Week.

Once a Week was a British literary magazine published by Bradbury & Evans from 1859 – 1880. The 9:30 Up-Train appeared in Series 1, Volume IX.

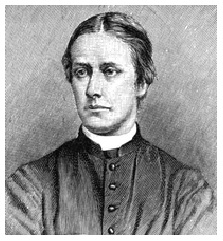

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

The 9:30 Up-Train by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

In a well-authenticated ghost story, names and dates should be distinctly specified. In the following story I am unfortunately able to give only the year and the month, for I have forgotten the date of the day, and I do not keep a diary. With regard to names, my own figures as a guarantee as that of the principal personage to whom the following extraordinary circumstances occurred, but the minor actors are provided with fictitious names, for I am not warranted to make their real ones public. I may add that the believer in ghosts may make use of the facts which I relate to establish his theories, if he finds that they will be of service to him—when he has read through and weighed well the startling account which I am about to give from my own experiences.

On a fine evening in June, 1860, I paid a visit to Mrs. Lyons, on my way to the Hassocks Gate Station, on the London and Brighton line. This station is the first out of Brighton.

As I rose to leave, I mentioned to the lady whom I was visiting that I expected a parcel of books from town, and that I was going to the station to inquire whether it had arrived.

“Oh!” said she, readily, “I expect Dr. Lyons out from Brighton by the 9.30 train; if you like to drive the pony chaise down and meet him, you are welcome, and you can bring your parcel back with you in it.”

I gladly accepted her offer, and in a few minutes I was seated in a little low basket-carriage, drawn by a pretty iron-grey Welsh pony.

The station road commands the line of the South Downs from Chantonbury Ring, with its cap of dark firs, to Mount Harry, the scene of the memorable battle of Lewes. Woolsonbury stands out like a headland above the dark Danny woods, over which the rooks were wheeling and cawing previous to settling themselves in for the night. Ditchling beacon—its steep sides gashed with chalk-pits—was faintly flushed with light. The Clayton windmills, with their sails motionless, stood out darkly against the green evening sky. Close beneath opens the tunnel in which, not so long before, had happened one of the most fearful railway accidents on record.

The evening was exquisite. The sky was kindled with light, though the sun was set. A few gilded bars of cloud lay in the west. Two or three stars looked forth—one I noticed twinkling green, crimson, and gold, like a gem. From a field of young wheat hard by I heard the harsh, grating note of the corncrake. Mist was lying on the low meadows like a mantle of snow, pure, smooth, and white; the cattle stood in it to their knees. The effect was so singular that I drew up to look at it attentively. At the same moment I heard the scream of an engine, and on looking towards the downs I noticed the up-train shooting out of the tunnel, its red signal lamps flashing brightly out of the purple gloom which bathed the roots of the hills.

Seeing that I was late, I whipped the Welsh pony on, and proceeded at a fast trot.

At about a quarter mile from the station there is a turnpike—an odd-looking building, tenanted then by a strange old man, usually dressed in a white smock, over which his long white beard flowed to his breast. This toll-collector—he is dead now—had amused himself in bygone days by carving life-size heads out of wood, and these were stuck along the eaves. One is the face of a drunkard, round and blotched, leering out of misty eyes at the passers-by; the next has the crumpled features of a miser, worn out with toil and moil; a third has the wild scowl of a maniac; and a fourth the stare of an idiot.

I drove past, flinging the toll to the door, and shouting to the old man to pick it up, for I was in a vast hurry to reach the station before Dr. Lyons left it. I whipped the little pony on, and he began to trot down a cutting in the greensand, through which leads the station road.

Suddenly, Taffy stood still, planted his feet resolutely on the ground, threw up his head, snorted, and refused to move a peg. I “gee-uped,” and “tshed,” all to no purpose; not a step would the little fellow advance. I saw that he was thoroughly alarmed; his flanks were quivering, and his ears were thrown back. I was on the point of leaving the chaise, when the pony made a bound on one side and ran the carriage up into the hedge, thereby upsetting me on the road. I picked myself up, and took the beast’s head. I could not conceive what had frightened him; there was positively nothing to be seen, except a puff of dust running up the road, such as might be blown along by a passing current of air. There was nothing to be heard, except the rattle of a gig or tax-cart with one wheel loose: probably a vehicle of this kind was being driven down the London road, which branches off at the turnpike at right angles. The sound became fainter, and at last died away in the distance.

The pony now no longer refused to advance. It trembled violently, and was covered with sweat.

“Well, upon my word, you have been driving hard!” exclaimed Dr. Lyons, when I met him at the station.

“I have not, indeed,” was my reply; “but something has frightened Taffy, but what that something was, is more than I can tell.”

“Oh, ah!” said the doctor, looking round with a certain degree of interest in his face; “so you met it, did you?”

“Met what?”

“Oh, nothing;—only I have heard of horses being frightened along this road after the arrival of the 9.30 up-train. Flys never leave the moment that the train comes in, or the horses become restive—a wonderful thing for a fly-horse to become restive, isn’t it?”

“But what causes this alarm? I saw nothing!”

“You ask me more than I can answer. I am as ignorant of the cause as yourself. I take things as they stand, and make no inquiries. When the flyman tells me that he can’t start for a minute or two after the train has arrived, or urges on his horses to reach the station before the arrival of this train, giving as his reason that his brutes become wild if he does not do so, then I merely say, ‘Do as you think best, cabby,’ and bother my head no more about the matter.”

“I shall search this matter out,” said I resolutely. “What has taken place so strangely corroborates the superstition, that I shall not leave it uninvestigated.”

“Take my advice and banish it from your thoughts. When you have come to the end, you will be sadly disappointed, and will find that all the mystery evaporates, and leaves a dull, commonplace residuum. It is best that the few mysteries which remain to us unexplained should still remain mysteries, or we shall disbelieve in supernatural agencies altogether. We have searched out the arcana of nature, and exposed all her secrets to the garish eye of day, and we find, in despair, that the poetry and romance of life are gone. Are we the happier for knowing that there are no ghosts, no fairies, no witches, no mermaids, no wood spirits? Were not our forefathers happier in thinking every lake to be the abode of a fairy, every forest to be a bower of yellow-haired sylphs, every moorland sweep to be tripped over by elf and pixie? I found my little boy one day lying on his face in a fairy-ring, crying: ‘You dear, dear little fairies, I will believe in you, though papa says you are all nonsense.’ I used, in my childish days, to think, when a silence fell upon a company, that an angel was passing through the room. Alas! I now know that it results only from the subject of weather having been talked to death, and no new subject having been started. Believe me, science has done good to mankind, but it has done mischief too. If we wish to be poetical or romantic, we must shut our eyes to facts. The head and the heart wage mutual war now. A lover preserves a lock of his mistress’s hair as a holy relic, yet he must know perfectly well that for all practical purposes a bit of rhinoceros hide would do as well—the chemical constituents are identical. If I adore a fair lady, and feel a thrill through all my veins when I touch her hand, a moment’s consideration tells me that phosphate of lime No. 1 is touching phosphate of lime No. 2—nothing more. If for a moment I forget myself so far as to wave my cap and cheer for king, or queen, or prince, I laugh at my folly next moment for having paid reverence to one digesting machine above another.”

I cut the doctor short as he was lapsing into his favourite subject of discussion, and asked him whether he would lend me the pony-chaise on the following evening, that I might drive to the station again and try to unravel the mystery.

“I will lend you the pony,” said he, “but not the chaise, as I am afraid of its being injured should Taffy take fright and run up into the hedge again. I have got a saddle.”

Next evening I was on my way to the station considerably before the time at which the train was due.

I stopped at the turnpike and chatted with the old man who kept it. I asked him whether he could throw any light on the matter which I was investigating. He shrugged his shoulders, saying that he “knowed nothink about it.”

“What! Nothing at all?”

“I don’t trouble my head with matters of this sort,” was the reply. “People do say that something out of the common sort passes along the road and turns down the other road leading to Clayton and Brighton; but I pays no attention to what them people says.”

“Do you ever hear anything?”

“After the arrival of the 9.30 train I does at times hear the rattle as of a mail-cart and the trot of a horse along the road; and the sound is as though one of the wheels was loose. I’ve a been out many a time to take the toll; but, Lor’ bless ‘ee! them sperits—if sperits them be—don’t go for to pay toll.”

“Have you never inquired into the matter?”

“Why should I? Anythink as don’t go for to pay toll don’t concern me. Do ye think as I knows ‘ow many people and dogs goes through this heer geatt in a day? Not I—them don’t pay toll, so them’s no odds to me.”

“Look here, my man!” said I. “Do you object to my putting the bar across the road, immediately on the arrival of the train?”

“Not a bit! Please yersel’; but you han’t got much time to lose, for theer comes thickey train out of Clayton tunnel.”

I shut the gate, mounted Taffy, and drew up across the road a little way below the turnpike. I heard the train arrive—I saw it puff off. At the same moment I distinctly heard a trap coming up the road, one of the wheels rattling as though it were loose. I repeat deliberately that I heard it—I cannot account for it—but, though I heard it, yet I saw nothing whatever.

At the same time the pony became restless, it tossed its head, pricked up its ears, it started, pranced, and then made a bound to one side, entirely regardless of whip and rein. It tried to scramble up the sand-bank in its alarm, and I had to throw myself off and catch its head. I then cast a glance behind me at the turnpike. I saw the bar bent, as though someone were pressing against it; then, with a click, it flew open, and was dashed violently back against the white post to which it was usually hasped in the day-time. There it remained, quivering from the shock.

Immediately I heard the rattle—rattle—rattle—of the tax-cart. I confess that my first impulse was to laugh, the idea of a ghostly tax-cart was so essentially ludicrous; but the reality of the whole scene soon brought me to a graver mood, and, remounting Taffy, I rode down to the station.

The officials were taking their ease, as another train was not due for some while; so I stepped up to the station-master and entered into conversation with him. After a few desultory remarks, I mentioned the circumstances which had occurred to me on the road, and my inability to account for them.

“So that’s what you’re after!” said the master somewhat bluntly. “Well, I can tell you nothing about it; sperits don’t come in my way, saving and excepting those which can be taken inwardly; and mighty comfortable warming things they be when so taken. If you ask me about other sorts of sperits, I tell you flat I don’t believe in ’em, though I don’t mind drinking the health of them what does.”

“Perhaps you may have the chance, if you are a little more communicative,” said I.

“Well, I’ll tell you all I know, and that is precious little,” answered the worthy man. “I know one thing for certain—that one compartment of a second-class carriage is always left vacant between Brighton and Hassocks Gate, by the 9.30 up-train.”

“For what purpose?”

“Ah! that’s more than I can fully explain. Before the orders came to this effect, people went into fits and that like, in one of the carriages.”

“Any particular carriage?”

“The first compartment of the second-class carriage nearest to the engine. It is locked at Brighton, and I unlock it at this station.”

“What do you mean by saying that people had fits?”

“I mean that I used to find men and women a-screeching and a-hollering like mad to be let out; they’d seen some’ut as had frightened them as they was passing through the Clayton tunnel. That was before they made the arrangement I told y’ of.”

“Very strange!” said I meditatively.

“Wery much so, but true for all that. I don’t believe in nothing but sperits of a warming and cheering nature, and them sort ain’t to be found in Clayton tunn’l to my thinking.”

There was evidently nothing more to be got out of my friend. I hope that he drank my health that night; if he omitted to do so, it was his fault, not mine.

As I rode home revolving in my mind all that I had heard and seen, I became more and more settled in my determination to thoroughly investigate the matter. The best means that I could adopt for so doing would be to come out from Brighton by the 9.30 train in the very compartment of the second-class carriage from which the public were considerately excluded.

Somehow I felt no shrinking from the attempt; my curiosity was so intense that it overcame all apprehension as to the consequences.

My next free day was Thursday, and I hoped then to execute my plan. In this, however, I was disappointed, as I found that a battalion drill was fixed for that very evening, and I was desirous of attending it, being somewhat behindhand in the regulation number of drills. I was consequently obliged to postpone my Brighton trip.

On the Thursday evening about five o’clock I started in regimentals with my rifle over my shoulder, for the drilling ground—a piece of furzy common near the railway station.

I was speedily overtaken by Mr. Ball, a corporal in the rifle corps, a capital shot and most efficient in his drill. Mr. Ball was driving his gig. He stopped on seeing me and offered me a seat beside him. I gladly accepted, as the distance to the station is a mile and three-quarters by the road, and two miles by what is commonly supposed to be the short cut across the fields.

After some conversation on volunteering matters, about which Corporal Ball was an enthusiast, we turned out of the lanes into the station road, and I took the opportunity of adverting to the subject which was uppermost in my mind.

“Ah! I have heard a good deal about that,” said the corporal. “My workmen have often told me some cock-and-bull stories of that kind, but I can’t say has ‘ow I believed them. What you tell me is, ‘owever, very remarkable. I never ‘ad it on such good authority afore. Still, I can’t believe that there’s hanything supernatural about it.”

“I do not yet know what to believe,” I replied, “for the whole matter is to me perfectly inexplicable.”

“You know, of course, the story which gave rise to the superstition?”

“Not I. Pray tell it me.”

“Just about seven years agone—why, you must remember the circumstances as well as I do—there was a man druv over from I can’t say where, for that was never exact-ly hascertained,—but from the Henfield direction, in a light cart. He went to the Station Inn, and throwing the reins to John Thomas, the ostler, bade him take the trap and bring it round to meet the 9.30 train, by which he calculated to return from Brighton. John Thomas said as ‘ow the stranger was quite unbeknown to him, and that he looked as though he ‘ad some matter on his mind when he went to the train; he was a queer sort of a man, with thick grey hair and beard, and delicate white ‘ands, jist like a lady’s. The trap was round to the station door as hordered by the arrival of the 9.30 train. The ostler observed then that the man was ashen pale, and that his ‘ands trembled as he took the reins, that the stranger stared at him in a wild habstracted way, and that he would have driven off without tendering payment had he not been respectfully reminded that the ‘orse had been given a feed of hoats. John Thomas made a hobservation to the gent relative to the wheel which was loose, but that hobservation met with no corresponding hanswer. The driver whipped his ‘orse and went off. He passed the turnpike, and was seen to take the Brighton road hinstead of that by which he had come. A workman hobserved the trap next on the downs above Clayton chalk-pits. He didn’t pay much attention to it, but he saw that the driver was on his legs at the ‘ead of the ‘orse. Next, morning, when the quarrymen went to the pit, they found a shattered tax-cart at the bottom, and the ‘orse and driver dead, the latter with his neck broken. What was curious, too, was that an ‘andkerchief was bound round the brute’s heyes, so that he must have been driven over the edge blindfold. Hodd, wasn’t it? Well, folks say that the gent and his tax-cart pass along the road every hevening after the arrival of the 9.30 train; but I don’t believe it; I ain’t a bit superstitious—not I!”

Next week I was again disappointed in my expectation of being able to put my scheme in execution; but on the third Saturday after my conversation with Corporal Ball, I walked into Brighton in the afternoon, the distance being about nine miles. I spent an hour on the shore watching the boats, and then I sauntered round the Pavilion, ardently longing that fire might break forth and consume that architectural monstrosity. I believe that I afterwards had a cup of coffee at the refreshment-rooms of the station, and capital refreshment-rooms they are, or were—very moderate and very good. I think that I partook of a bun, but if put on my oath I could not swear to the fact; a floating reminiscence of bun lingers in the chambers of memory, but I cannot be positive, and I wish in this paper to advance nothing but reliable facts. I squandered precious time in reading the advertisements of baby-jumpers—which no mother should be without—which are indispensable in the nursery and the greatest acquisition in the parlour, the greatest discovery of modern times, etc., etc. I perused a notice of the advantage of metallic brushes, and admired the young lady with her hair white on one side and black on the other; I studied the Chinese letter commendatory of Horniman’s tea and the inferior English translation, and counted up the number of agents in Great Britain and Ireland. At length the ticket-office opened, and I booked for Hassocks Gate, second class, fare one shilling.

I ran along the platform till I came to the compartment of the second-class carriage which I wanted. The door was locked, so I shouted for a guard.

“Put me in here, please.”

“Can’t there, s’r; next, please, nearly empty, one woman and baby.”

“I particularly wish to enter this carriage,” said I.

“Can’t be, lock’d, orders, comp’ny,” replied the guard, turning on his heel.

“What reason is there for the public’s being excluded, may I ask?”

“Dn’ow, ‘spress ord’rs—c’n’t let you in; next caridge, pl’se; now then, quick, pl’se.”

I knew the guard and he knew me—by sight, for I often travelled to and fro on the line, so I thought it best to be candid with him. I briefly told him my reason for making the request, and begged him to assist me in executing my plan. He then consented, though with reluctance.

“‘Ave y’r own way,” said he; “only if an’thing ‘appens, don’t blame me!”

“Never fear,” laughed I, jumping into the carriage.

The guard left the carriage unlocked, and in two minutes we were off.

I did not feel in the slightest degree nervous. There was no light in the carriage, but that did not matter, as there was twilight. I sat facing the engine on the left side, and every now and then I looked out at the downs with a soft haze of light still hanging over them. We swept into a cutting, and I watched the lines of flint in the chalk, and longed to be geologising among them with my hammer, picking out “shepherds’ crowns” and sharks’ teeth, the delicate rhynconella and the quaint ventriculite. I remembered a not very distant occasion on which I had actually ventured there, and been chased off by the guard, after having brought down an avalanche of chalk débris in a manner dangerous to traffic whilst endeavouring to extricate a magnificent ammonite which I found, and—alas! left—protruding from the side of the cutting. I wondered whether that ammonite was still there; I looked about to identify the exact spot as we whizzed along; and at that moment we shot into the tunnel.

There are two tunnels, with a bit of chalk cutting between them. We passed through the first, which is short, and in another moment plunged into the second.

I cannot explain how it was that now, all of a sudden, a feeling of terror came over me; it seemed to drop over me like a wet sheet and wrap me round and round.

I felt that someone was seated opposite me—someone in the darkness with his eyes fixed on me.

Many persons possessed of keen nervous sensibility are well aware when they are in the presence of another, even though they can see no one, and I believe that I possess this power strongly. If I were blindfolded, I think that I should know when anyone was looking fixedly at me, and I am certain that I should instinctively know that I was not alone if I entered a dark room in which another person was seated, even though he made no noise. I remember a college friend of mine, who dabbled in anatomy, telling me that a little Italian violinist once called on him to give a lesson on his instrument. The foreigner—a singularly nervous individual—moved restlessly from the place where he had been standing, casting many a furtive glance over his shoulder at a press which was behind him. At last the little fellow tossed aside his violin, saying—

“I can note give de lesson if someone weel look at me from behind! Dare is somebodee in de cupboard, I know!”

“You are right, there is!” laughed my anatomical friend, flinging open the door of the press and discovering a skeleton.

The horror which oppressed me was numbing. For a few moments I could neither lift my hands nor stir a finger. I was tongue-tied. I seemed paralysed in every member. I fancied that I felt eyes staring at me through the gloom. A cold breath seemed to play over my face. I believed that fingers touched my chest and plucked at my coat. I drew back against the partition; my heart stood still, my flesh became stiff, my muscles rigid.

I do not know whether I breathed—a blue mist swam before my eyes, and my head span.

The rattle and roar of the train dashing through the tunnel drowned every other sound.

Suddenly we rushed past a light fixed against the wall in the side, and it sent a flash, instantaneous as that of lightning, through the carriage. In that moment I saw what I shall never, never forget. I saw a face opposite me, livid as that of a corpse, hideous with passion like that of a gorilla.

I cannot describe it accurately, for I saw it but for a second; yet there rises before me now, as I write, the low broad brow seamed with wrinkles, the shaggy, over-hanging grey eyebrows; the wild ashen eyes, which glared as those of a demoniac; the coarse mouth, with its fleshy lips compressed till they were white; the profusion of wolf-grey hair about the cheeks and chin; the thin, bloodless hands, raised and half-open, extended towards me as though they would clutch and tear me.

In the madness of terror, I flung myself along the seat to the further window.

Then I felt that it was moving slowly down, and was opposite me again. I lifted my hand to let down the window, and I touched something: I thought it was a hand—yes, yes! it was a hand, for it folded over mine and began to contract on it. I felt each finger separately; they were cold, dully cold. I wrenched my hand away. I slipped back to my former place in the carriage by the open window, and in frantic horror I opened the door, clinging to it with both my hands round the window-jamb, swung myself out with my feet on the floor and my head turned from the carriage. If the cold fingers had but touched my woven hands, mine would have given way; had I but turned my head and seen that hellish countenance peering out at me, I must have lost my hold.

Ah! I saw the light from the tunnel mouth; it smote on my face. The engine rushed out with a piercing whistle. The roaring echoes of the tunnel died away. The cool fresh breeze blew over my face and tossed my hair; the speed of the train was relaxed; the lights of the station became brighter. I heard the bell ringing loudly; I saw people waiting for the train; I felt the vibration as the brake was put on. We stopped; and then my fingers gave way. I dropped as a sack on the platform, and then, then—not till then—I awoke. There now! from beginning to end the whole had been a frightful dream caused by my having too many blankets over my bed. If I must append a moral—Don’t sleep too hot.

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)