Public Domain Text: Naboth’s Vineyard by E. F. Benson

“Naboth’s Vineyard” is taken from Benson’s Spook Stories anthology (1928). Benson’s inspiration appears to have been a biblical story of the same name.

Both stories are about men who go to vile lengths to covet the land of another. In the case of the Biblical story, a king wants the vineyard that belongs to a Jezreelite named Naboth. In Benson’s story, a lawyer who is keen to retire sets his heart on a house the owners do not wish to sell. In both tales, one way or another, the perpetrators come to a bad end.

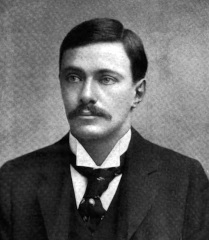

About E. F. Benson

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

Naboth’s Vineyard

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

Ralph Hatchard had for the last twenty years been making a very good income at the Bar; no one could marshal facts so tellingly as he, no one could present a case to a jury in so persuasive and convincing a way, nor make them see the situation he pictured to them with so sympathetic an eye. He disdained to awaken sentiment by moving appeals to humanity, for he had not, either in his private or his public life, any use for mercy, but demanded mere justice for his client. Many were the cases in which, not by distorting facts, but merely by focusing them for the twelve intelligent men whom he addressed, he had succeeded in making them look through the telescope of his mind, and see at the end of it precisely what he wished them to see. But if he had been asked of which out of all his advocacies he was most intellectually proud, he would probably have mentioned one in which that advocacy had not been successful. This was in the famous Wraxton case of seven years ago, in which he had defended a certain solicitor, Thomas Wraxton, on a charge of embezzlement and conversion to his own use of the money of a client.

As the case was presented by the prosecution, it seemed as if any defence would merely waste the time of the court, but when the speech for the defence was concluded, most of them who heard it, not the public alone, but the audience of trained legal minds, would probably have betted (had betting been permitted in a court of justice) that Thomas Wraxton would be acquitted. But the twelve intelligent men were among the minority, and after being absent from court for three hours had brought in a verdict of guilty. A sentence of seven years was passed on Thomas Wraxton, and his counsel, thoroughly disgusted that so much ingenuity should have been thrown away, felt, ever afterward, a sort of contemptuous irritation with him. The irritation was rendered more acute by an interview he had with Wraxton after sentence had been passed. His client raged and stormed at him for the stupidity and lack of skill he had shown in his defence.

Hatchard was a bachelor; he had little opinion of women as companions, and it was enough for him in town when his day’s work was over to take his dinner at the club, and after a stern rubber or two at bridge, to retire to his flat, and more often than not work at some case in which he was engaged till the small hours. Apart from the dinner-table and the card-table, the only companion he wanted was an opponent at golf for Saturday and Sunday, when he went down for his week-end to the seaside links at Scarling. There was a pleasant dormy-house in the town, at which he put up, and in the summer he was accustomed to spend the greater part of the long vacation here, renting a house in the neighbourhood. His only near relation was a brother who had a Civil Service appointment at Bareilly, in the North-West province of India, whom he had not seen for some years, for he spent the hot season in the hills and but seldom came to England.

Hatchard got from acquaintances all the friendship that he needed, and though he was a solitary man, he was by no means to be described as a lonely one. For loneliness implies the knowledge that a man is alone, and his wish that it were otherwise. Hatchard knew he was alone, but preferred it. His golf and his bridge of an evening gave him all the companionship he needed; a further recreation of his was botany. “Plants are good to look at, they’re interesting to study, and they don’t bore you by unwished-for conversation” would have been his manner of accounting for so unexpected a hobby. He intended, when he retired from practice, to buy a house with a good garden in some country town, where he could enjoy at leisure this trinity of innocuous amusements. Till then, there was no use in having a garden from which his work would sever him for the greater part of the year.

He always took the same house at Scarling when he came to spend his long vacation there. It suited him admirably, for it was within a few doors of the local club, where he could get a rubber in the evening, and find a match at golf for next day, and the motor omnibuses that plied along the seaside road to the links passed his door. He had long ago settled in his mind that Scarling was to be the home of his late and leisured years, and of all the houses in that compact mediæval little town the one which he most coveted lay close to that which he was now accustomed to take for the summer months. Opposite his windows ran the long red-brick wall of its garden, and from his bedroom above he could look over this and see the amenities which in its present proprietorship seemed so sadly undervalued.

An acre of lawn with a gnarled and sprawling mulberry tree lay there, a pergola of rambler-roses separated this from the kitchen garden, and all round in the shelter of the walls which defended them from the chill northerly and easterly blasts lay deep flower beds. A paved terrace faced the garden side of Telford House, but weeds were sprouting there, the grass of the lawn had been suffered to grow long and rank, and the flower beds were an untended jungle. The house, too, seemed exactly what would suit him, it was of Queen Anne date, and he could conjecture the square panelled rooms within. He had been to the house-agent’s in Scarling to ask if there was any chance of obtaining it, and had directed him to make inquiries of the occupying tenant or proprietor as to whether he had any thoughts of getting rid of it to a purchaser who was prepared to negotiate at once for it. But it appeared that it had only been bought some six years ago by the present owner, Mrs. Pringle, when she came to live at Scarling, and she had no idea of parting with it.

Ralph Hatchard, when he was at Scarling, took no part whatever in the local life and society of the place except in so far as he encountered it among the men whom he met in the card-room of the club and out at the links, and it appeared that Mrs. Pringle was as recluse as he. Once or twice in casual conversation mention had been made by one or another of her house or its owner, but nothing was forthcoming about her. He learned that when she had come there first, the usual country-town civilities had been paid her, but she either did not return the call or soon suffered the acquaintanceship to drop, and at the present time she appeared to see nobody except occasionally the vicar of the church or his wife. Hatchard made no particular note of all this, and did not construct any such hypothesis as might be supposed to divert the vagrant thoughts of a legal mind by picturing her as a woman hiding from justice or from the exposure that justice had already subjected her to. As far as he was aware he had never set eyes on her, nor had he any object in wishing to do so, as long as she was not willing to part with her house; it was sufficient for a man who was not in the least inquisitive (except when conducting a cross-examination) to suppose that she liked her own company well enough to dispense with that of others. Plenty of sensible folk did that, and he thought no worse of them for it.

More than six years had now elapsed since the Wraxton trial, and Hatchard was spending the last days of the long vacation at the house that overlooked that Naboth’s vineyard of a garden. The day was one of squealing wind and driving rain, and even he, who usually defied the elements to stop his couple of rounds of golf, had not gone out to the links to-day. Towards evening, however, it cleared, and he set out to get a mouthful of fresh air and a little exercise, and returned just about sunset past the house he coveted. There were two women standing on the threshold as he approached, one of them hatless, and it came into his mind that here, no doubt, was the retiring Mrs. Pringle. She stood side-face to him for that moment, and at once he knew that he had seen her before; her face and her carriage were perfectly but remotely familiar to him. Then she turned and saw him; she gave him but one glance, and without pause went back into the house and shut the door. The sight he had of her was but instantaneous, but sufficient to convince him not only that he had seen her before, but that she was in no way desirous of seeing him again.

Mrs. Grampound, the vicar’s wife, had been talking to her, and Hatchard raised his hat, for he had been introduced to her one day when he had been playing golf with her husband. He alluded to the malignity of the weather, which, after being wet all day, was clearly going to be uselessly fine all night.

“And that lady, I suppose,” he said, “with whom you were speaking, was Mrs. Pringle? A widow, perhaps? One does not meet her husband at the club.”

“No; she is not a widow,” said Mrs. Grampound. “Indeed, she told me just now that she expected her husband home before long. He has been out in India for some years.”

“Indeed! I heard only to-day from my brother, who is also in India. I expect him home in the spring for six months’ leave. Perhaps I shall find that he knows Mr. Pringle.”

They had come to his house, and he turned in. Somehow, Mrs. Pringle had ceased to be merely the owner of the house he so much desired. She was somebody else, and good though his memory was, he could not recall where he had met her before. He could not in the least remember the sound of her voice, perhaps he had never heard it. But he knew her face.

During the winter he was often down at Scarling again for his week-ends, and now he was definitely intending to retire from practice before the summer. He had made sufficient money to live with all possible comfort, and he was certainly beginning to feel the strain of his work. His memory was not quite what it had been, and he who had been robust as a piece of ironwork all his life, had several times been in the doctor’s hands. It was clearly time, if he was going to enjoy the long evening of life, to begin doing so while the capacity for enjoyment was still unimpaired, and not linger on at work till his health suffered. He could not concentrate as he had been used; even when he was most occupied in his own argument the train of his thought would grow dim, and through it, as if through a mist, vague images of thought would fleetingly appear, images not fully tangible to his mind, and evade him before he could grasp them.

That logical constructive brain of his was certainly getting tired with its years of incessant work, and knowing that, he longed more than ever to have done with business, and more vividly than ever he saw himself established in that particular house and garden at Scarling. The thought of it bid fair to become an obsession with him; he began to look upon Mrs. Pringle as an enemy standing in the way of the fulfilment of his dream, and still he cudgelled his brain to think when and where and how he had seen her before. Sometimes he seemed close to the solution of that conundrum, but just as he pounced on it, it slipped away again, like some object in the dusk.

He was down there one week-end in March and instead of playing golf, spent his Saturday morning in looking over a couple of houses which were for sale. His brother, whom he now expected back in a week or two, and who, like himself, was a bachelor, would be living with him all the summer, and now at last despairing of getting the house he wanted, he must resign himself to the inevitable, and get some other permanent home. One of these two houses, he thought, would do for him fairly well, and after viewing it he went to the house agent’s and secured the first refusal of it, with a week in which to make up his mind.

“I shall almost certainly purchase it,” he said, “for I suppose there is still no chance of my getting Telford House.”

The agent shook his head.

“I’m afraid not, sir,” he said. “Mr. Pringle, you may have heard, has come home, and lives there now.”

As he left the office an idea occurred to him. Though Mrs. Pringle might not, when living there alone, have felt disposed to face the inconvenience of moving, it was possible that a firm and adequate offer made to her husband might effect something. He had only just come there, it was not to be supposed that he had any very strong attachment to the house, and a definite offer of so many thousand pounds down might perhaps induce him to give it up. Hatchard determined, before definitely purchasing another house, to make a final effort to get that on which his heart was set.

He went straight to Telford House and rang. He gave the maid his card, asking if he could see Mr. Pringle, and at that moment a man came into the little hall from the door into the garden, and seeing someone there paused as he entered. He was a tall fellow, but bent; and walked limpingly with the aid of a stick. He wore a short grey beard and moustache, his eyes were sunk deep below the overhanging brows.

Hatchard gave one glance at him, and a curious thing happened. Instantly there sprang into his mind not, first of all, the knowledge of who this man was, but the knowledge which had so long evaded him. He remembered everything: Mrs. Pringle’s white, drawn face as she looked at the jury filing into the box again at the end of their consultation, in which they had decided the guilt or the innocence of Thomas Wraxton. No wonder she was all suspense and anxiety, for it was her husband’s fate that was being decided. And then, a moment afterwards, he could trace in the face of the man who stood at the garden door the shattered identity of him who had stood in the dock. But had it not been for his wife, he thought he would not have recognised him, so terribly had suffering changed him. He looked very ill, and the high colour in his face clearly pointed to a weakness of the heart rather than a vigorous circulation.

Hatchard turned to him. He did not intend to use his deadliest weapon unless it was necessary. But at that moment he told himself that Telford House would be his.

“You will excuse me, Mr. Pringle,” he said, “for calling on you so unceremoniously. My name is Hatchard, Ralph Hatchard, and I should be most grateful if you would let me have a few minutes’ conversation with you.”

Pringle took a step forward. He told himself that he had not been recognised; that was no wonder. But the shock of the encounter had left him trembling.

“Certainly,” he said; “shall we go into my room here?”

The two went into a little sitting-room close by the front door.

“My business is quite short,” said Hatchard. “I am on the look-out for a house here, and of all the houses in Scarling yours is the one which I have long wanted. I am willing to pay you £6,000 pounds for it. I may add that there is an extremely pleasant house, which I have the option to purchase, which you can obtain for half that sum.”

Pringle shook his head.

“I am not thinking of parting with my house,” he said.

“If it is a matter of price,” said Hatchard, “I am willing to make it £6,500.”

“It is not a matter of price,” said Pringle. “The house suits my wife and me, and it is not for sale.”

Hatchard paused a moment. The man had been his client, but a guilty and a very ungrateful one.

“I am quite determined to get this house, Mr. Pringle,” he said. “You will make, I feel sure, a very handsome profit by accepting the price I offer, and if you are attached to Scarling you will be able to purchase a very convenient residence!”

“The house is not for sale,” said Pringle.

Hatchard looked at him closely.

“You will be more comfortable in the other house,” he said. “You will live there, I assure you, in peace and security, and I hope you will spend many pleasant years there as Mr. Pringle from India. That will be better than being known as Mr. Thomas Wraxton, of His Majesty’s prison.”

The wretched man shrunk into a mere nerveless heap in his chair, and wiped his forehead.

“You know me, then?” he said.

“Intimately, I may say,” retorted Hatchard.

Five minutes later, Hatchard left the house. He had in his pocket Mr. Pringle’s acceptance of his offer of £6,500 for Telford House with possession in a month’s time. That night the doctor was hurriedly sent for to Telford House, but his skill was of no avail against the heart attack which proved fatal to his patient.

Ralph Hatchard was sitting on the flagged terrace on the garden side of his newly-acquired house one warm evening in May. He had spent his morning on the links with his brother Francis, his afternoon in the garden, weeding and planting, and now he was glad enough to sprawl in his low easy basket-chair and glance at the paper which he had not yet read. He had been a month here, and looking back through his happy and busy life, he could not recollect having ever been busier and happier. It was said, how falsely he now knew, that if a man gave up his work, he often went downhill both in mind and body, growing stout and lazy and losing that interest in life which keeps old-age in the background, but the very opposite had been his own experience. He played his golf and his bridge with just as much zest as when they had been the recreation from his work, and he found time now for serious reading. He gardened, too, you might say with gluttony; awaking in the morning found him refreshed and eager for the pleasurable toil and exercise of the day, and every evening found him ready for bed and long dreamless sleep.

He sat, alone for the time being, content to take his ease and glance at the news. Even now he gave but a cursory attention to it and his eye wandered over the lawn, and the long-neglected flower-beds, which the joint labours of the gardener and himself were quickly bringing back into orderly cultivation. The lawn must be cut to-morrow, and there were some late-flowering roses to be planted. Then perhaps he dozed a little, for though he had heard no one approach, there was the sound of steps somewhere at his back quite close to him, and the tapping of a stick on the paving-stones of the terrace. He did not look round, for of course it must be Francis returned from his shopping; he had occasional twinges of rheumatism which made him a little lame, but Ralph had not noticed till to-day that he limped like that.

“Is your rheumatism bothering you, Francis?” he said, still not looking round. There was no answer and he turned his head. The terrace was quite empty: neither his brother nor anyone else was there.

For the moment he was startled: then he was aware that he certainly had been dozing, for his paper had slipped off his knee without his noticing it. No doubt this impression was the fag-end of some dream. Confirmation of that immediately came, for there in the street outside was the noise of a tapping footfall; it was that no doubt that had mingled itself with some only half-waking impression. He had dreamed, too, now that he came to think about it; he had dreamed something about poor Wraxton. What it was he could not recollect, beyond that Wraxton was angry with him and railed at him just as he had done after that long sentence had been passed on him.

The sun had set, and there was a slight chill in the air which caused him a moment’s goose-flesh. So getting out of his basket-chair he took a turn along the gravel path which bordered the lawn, his eye dwelling with satisfaction on the labours of the day. The bed had been smothered in weeds a week ago; now there was not a weed to be seen on it. Ah! just one; that small piece of chickweed had evaded notice, and he bent down to root it up. At that moment he heard the limping step again, not in the street at all, but close to him on the terrace, and the basket-chair creaked, as if someone had sat down in it. But again the terrace was void of occupants, and his chair empty.

It would have been strange indeed if a man so hard-headed and practical as Hatchard had allowed himself to be disturbed by an echoing stone and a creaking chair, and it was with no effort that he dismissed them. He had plenty to occupy him without that, but once or twice in the next week he received impressions which he definitely chucked into the lumber-room of his mind as among the things for which he had no use. One morning, for instance, after the gardener had gone to his dinner, he thought he saw him standing on the far side of the mulberry tree, half screened by the foliage. He took the trouble to walk round the tree on this occasion, but found no one there, neither his gardener nor any other, and coming back to the place where he had received this impression, he saw (and was secretly relieved to see) that a splash of light on the wall beyond might have tricked him into constructing a human figure there. But though his waking moments were still untroubled he began to sleep badly, and when he slept to be the prey of vivid and terrible dreams, from which he would awake in disordered panic.

The recollection of these was vague, but always he had been pursued by something invisible and angry that had come in from the garden, and was limping swiftly after him upstairs and along the passage at the end of which his room lay. Invariably, too, he just escaped into his room before the pursuer clutched him, and banged his door, the crash of which (in his dream) awoke him. Then he would turn on the light, and, despite himself, cast a glance at the door, and the oblong of glass above it which gave light to this dark end of the passage, as if to be sure that nothing was looking through it; and once, upbraiding himself for his cowardice, he had gone to the door and opened it, and turned on the light in the passage outside. But it was empty.

By day he was master of himself, though he knew that his self-control was becoming a matter that demanded effort. Often and often, though still nothing was visible, he heard the limping steps on the terrace and along the weeded gravel-path; but instead of becoming used to so harmless an hallucination, which seemed to usher in nothing further, he grew to fear it. But until a certain day, it was only in the garden that he heard that step.

July was now half way through, when a broiling morning was succeeded by a storm that raced up from the south. Thunder had been remotely muttering for an hour or two, and now as he worked on the garden beds, the first large tepid drops of rain warned him that the downpour was imminent, and he had scarcely reached the door into the hall when it descended. The sluices of heaven were opened, and thick as a tropical tempest the rain splashed and steamed on the terrace. As he stood in the doorway, he heard the limping step come slowly and unhurried through the deluge, and up to the door where he stood. But it did not pause there; he felt something invisible push by him, he heard the steps limp across the hall within, and the door of the sitting-room, where he had sat one morning in March and watched Wraxton’s tremulous signature traced on the paper, swing open and close again.

Ralph Hatchard stood steady as a rock, holding himself firmly in hand. “So it’s come into the house,” he said to himself. “So it’s come in—ha!—out of the rain,” he added. But he knew, when that unseen presence had pushed by him to the door, that at that moment terror real and authentic had touched some inmost fibre of him. That touch had quitted him now; he could reassert his dominion over himself, and be steady, but as surely as that unseen presence had entered the house, so surely had fear found entry into his soul.

All the afternoon the rain continued; golf and gardening were alike out of the question, and presently he went round to the club to find a rubber of bridge. He was wise to be occupied, occupation was always good, especially for one who now had in his mind a prohibited area where it was better not to graze. For something invisible and angry had come into the house, and he must starve it into quitting it again, not by facing it and defying it, but by the subtler and the safe process of denying and disregarding it. A man’s soul was his own enclosed garden, nothing could obtain admittance there without his invitation and permission. He must forget it till he could afford to laugh at the fantastic motive of its existence. Besides, the perception of it was purely subjective, so he argued to himself: it had no real existence outside himself; his brother, for instance, and the servants were quite unaware of the limping steps that so constantly were heard by him. The invisible phantom was the product of some derangement of his own senses, some misfunction of the nerves. To convince himself of that, as he passed through the hall on his way to the club, he went into the room into which the limping steps had passed. Of course there was nothing there, it was just the small quiet, unoccupied sitting-room that he knew.

There was some brisk bridge, which he enjoyed in his usual grim and magisterial manner, and dusk, hastened on by the thick pall of cloud which still overset the sky, was falling when he got back home again. He went into the panelled sitting-room looking out on the garden, and found Francis there, cheery and robust. The lamps were lit, but the blinds and curtains not yet drawn, and outside an illuminated oblong of light lay across the terrace.

“Well, pleasant rubbers?” asked Francis.

“Very decent,” said Ralph. “You’ve not been out?”

“No, why go out in the rain, when there’s a house to keep you dry? By the way, have you seen your visitor?”

Ralph knew that his heart checked and missed a beat. Had that which was invisible to him become visible to another? Then he pulled himself together; why shouldn’t there have been a visitor to see him?

“No,” he said, “who was it?”

Francis beat out his pipe against the bars of the grate.

“I’m sure I don’t know,” he said. “But ten minutes ago, I passed through the hall, and there was a man sitting on a chair there. I asked him what he wanted, and he said he was waiting to see you. I supposed it was somebody who had called by appointment, and I said you would no doubt be in presently, and suggested that he would be more comfortable in that little sitting-room than waiting in the hall. So I showed him in there, and shut the door on him.”

Ralph rang the bell.

“Who is it who has called to see me?” he asked the parlourmaid.

“Nobody, sir, that I know of,” she said; “I haven’t let anyone in!”

“Well, somebody has called,” he said, “and he’s in the little sitting-room near the front door. Just see who it is; and ask him his name and his business.”

He paused a moment, making a call on his courage.

“No; I’ll go myself,” he said.

He came back in a few seconds.

“Whoever it was, he has gone,” he said. “I suppose he got tired of waiting. What was he like, Francis?”

“I couldn’t see him very distinctly, for it was pretty dark in the hall. He had a grey beard, I saw that, and he walked with a limp.”

Ralph turned to the window to pull down the blind. At that moment he heard a step on the terrace outside, and there stepped into the illuminated oblong the figure of a man. He leaned heavily on a stick as he walked, and came close up to the window, his eyes blazing with some devilish fury, his mouth mumbling and working in his beard. Then down came the blind, and the rattle of the curtain-rings along the pole followed.

The evening passed quietly enough: the two brothers dined together, and played a few hands at piquet afterwards, and before going up to bed looked out into the garden to see what promise the weather gave. But the rain still dripped, and the air was sultry with storm. Lightning quivered now and again in the west, and in one of these blinks Francis suddenly pointed towards the mulberry-tree.

“Who is that?” he said.

“I saw no one,” said Ralph.

Once more the lightning made things visible, and Francis laughed.

“Ah! I see,” he said. “It’s only the trunk of the tree and that grey patch of sky through the leaves. I could have sworn there was somebody there. That’s a good example of how ghost stories arise. If it had not been for that second flash, we should have searched the garden, and, finding nobody, I should have been convinced I had seen a ghost!”

“Very sound,” said Ralph.

He lay long awake that night, listening to the hiss of the rain on the shrubs outside his window, and to a footfall that moved about the house.

The next few days passed without the renewal of any direct manifestations of the presence that had entered the house. But the cessation of it brought no relief to the pressure of some force that seemed combing in over Ralph Hatchard’s mind. When he was out on the links or at the club it relaxed its hold on him, but the moment he entered his door it gripped him again. It mattered not that he neither saw nor heard anything for which there was no normal and material explanation; the power, whatever it was, was about his path and about his bed, driving terror into him. He confessed to strange lassitude and depression, and eventually yielded to his brother’s advice, and made an appointment with his doctor in town for next day.

“Much the wisest course,” said Francis. “Doctors are a splendid institution. Whenever I feel down I go and see one, and he always tells me there’s nothing the matter. In consequence I feel better at once. Going up to bed? I shall follow in half an hour. There’s an amusing tale I’m in the middle of.”

“Put out the light then,” said Ralph, “and I’ll tell the servants they can go to bed.”

The half-hour lengthened into an hour, and it was not much before midnight that Francis finished his tale. There was a switch in the hall to be turned off, and another half-way up the stairs. As his finger was on this, he looked up to see that the passage above was still lit, and saw, leaning on the banister at the top of the stairs the figure of a man. He had already put out the light on the stairs, and this figure was silhouetted in black against the bright background of the lit passage. For a moment he supposed that it must be his brother, and then the man turned, and he saw that he was grey-bearded, and limped as he walked.

“Who the devil are you?” cried Francis.

He got no reply, but the figure moved away up the passage, at the end of which was Ralph’s room. He was now in full pursuit after it, but before he had traversed one half of the passage it was already at the end of it, and had gone into his brother’s room. Strangely bewildered and alarmed, he followed, knocked on Ralph’s door, calling him loudly by name, and turned the handle to enter. But the door did not yield for all his pushing, and again “Ralph! Ralph!” he called aloud, but there was no answer.

Above the door was a glass pane that gave light to the passage, and looking up he saw that this was black, showing that the room was in darkness within. But even as he looked, it started into light, and simultaneously from inside there rose a cry of mortal agony.

“Oh, my God, my God!” rang out his brother’s voice, and again that cry of agony resounded.

Then there was another voice, speaking low and angry.

“No, no!” yelled Ralph again, and again in a panic of fear Francis put his shoulder to the door and strove quite in vain to open it, for it seemed as if the door had become a part of the solid wall.

Once more that cry of terror burst out, and then, whatever was taking place within, was all over, for there was dead silence. The door which had resisted his most frenzied efforts now yielded to him, and he entered.

His brother was in bed, his legs drawn up close under him, and his hands, resting on his knees, seemed to be attempting to beat off some terrible intruder. His body was pressed against the wall at the head of the bed, and the face was a mask of agonised horror and fruitless entreaty. But the eyes were already glazed in death, and before Francis could reach the bed the body had toppled over and lay inert and lifeless. Even as he looked, he heard a limping step go down the passage outside.

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)